NOTE: Articles 90 – 93 on Navigational tools for Church Missions have been revised and incorporated into a single article through Catalyst Services.

The transitions and tools described in this series of articles are used as the framework for missions coaching among Fellowship churches in Canada. If you are interested in exploring a coaching relationship for your church’s missions efforts, please contact Mark via the contact link below.

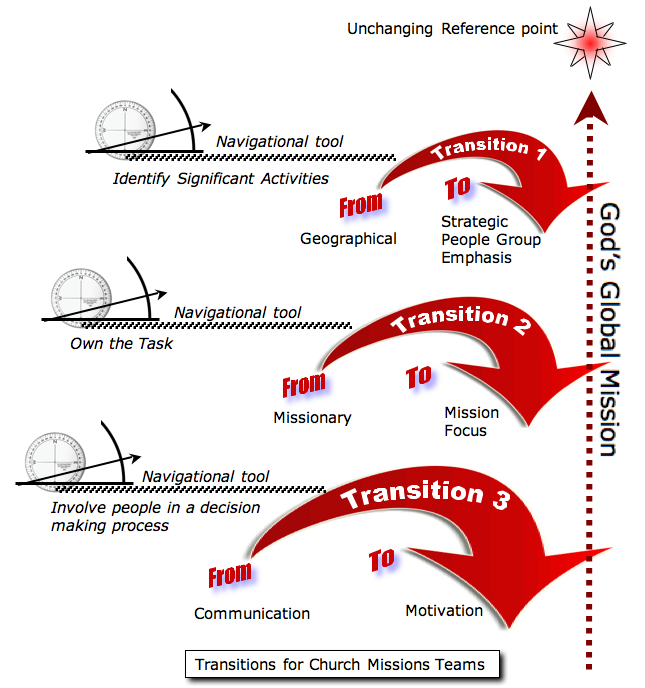

In the previous article, a second transition to move the missions team1 in the direction of “owning the task” was considered. This article elaborates on the third transition for church missions teams introduced in Navigational tools for missions.

Transition 3: From communicating with to motivating the congregation

Navigational tool: Involve people in a decision making process

Biblical foundation: One body, many gifts

“I give up!” said Dave2, a missions chair. He had faithfully and conscientiously kept the needs of the missionaries before the church. His discouragement was evident, “Every week I have information about our missionaries in the bulletin. Then this last Sunday while talking to one of the elders I mention one of our missionaries and he asks me who they are! He didn’t even know we supported them. What a waste of time.”

“I give up!” said Dave2, a missions chair. He had faithfully and conscientiously kept the needs of the missionaries before the church. His discouragement was evident, “Every week I have information about our missionaries in the bulletin. Then this last Sunday while talking to one of the elders I mention one of our missionaries and he asks me who they are! He didn’t even know we supported them. What a waste of time.”

I was on the phone recently to one of our churches and spoke to the pastor’s assistant. I mentioned the name of a missionary who has been supported for years by the church, but she was unaware of who he was. When faced with the reality that many people in the church lack knowledge about their church’s missionaries, a common response by missions teams is to increase communication. The assumption seems to be that providing more information to the congregation will result in greater understanding about missions and an increase in commitment to the missions program.

people only retain information that is immediately perceived as relevant

Unfortunately, increased information does not necessarily result in greater involvement by the congregation or even alter people’s awareness of the missionaries’ work. One reason for this reality is that, in general, people only retain information that is immediately perceived as relevant, the rest is dismissed. In our information saturated age, people have developed extremely efficient filters; any information that does seem relevant is dismissed and forgotten. Increasing communication is, therefore, a waste of time if there is no corresponding increase in personal relevance. Whether watching TV, surfing the internet or scanning the church bulletin, people connect with what interests them, and immediately discard that which does not relate to their lives. Buy-in and ownership are a priori requirements in order for information to be valued and accepted. Providing more information without also ensuring perceived relevance for the intended hearer results in little or no impact.

This article advocates for a transition from a communication emphasis to a process of motivating the congregation. Once people are motivated, communication is effective.

How does motivation work?

Motivation follows a distinct pattern:

1. Motivation is the natural orientation of people who have ownership

1. Motivation is the natural orientation of people who have ownership

If your neighbor tells you that their car needs a tune-up, the chances are that you would not receive that information as a call to action. Because you do not own the car, nor are responsible for it, you listen with only mild interest. However, if it was your car, the natural response would be to take steps to correct the problem.

2. Ownership is the acceptance of ongoing responsibility initiated by an act of commitment.

When you sign the papers to purchase a house, perform your wedding vows, make a promise or merely hand over money to buy a litre of milk, you have committed yourself to a particular action or relationship. There is an obligation or expectation that you will follow through on the implications of that commitment. You will live in the house, care for your spouse, fulfill your promise and take the milk home.

3. Commitment is the end result of a decision making process

Why do people commit? There are a number of steps a person must go through to get to the point of commitment. A series of decisions precede the act of binding oneself to a particular relationship, whether it is something as simple as purchasing milk, or as life-changing as getting married. The decision making process leading up to the commitment may be incremental and develop slowly, or it may occur quickly with little hesitation, but it is a necessary prerequisite for a person to make a legitimate and sincere commitment.

A decision making process leads to commitment, which creates ownership, which causes motivation

Information makes sense when (and only when) there is perceived relevance. Perceived relevance stems from a sense of ownership (buy-in) to a particular issue. Ownership requires an act of commitment. Commitment is developed through a process of involvement and decision making. If people are not responding well to communication about missions in the church, the likely cause is a lack of perceived relevance. In that case, the job of the missions team is not more or better communication. Rather the task becomes one of developing commitment by involving people in a decision making process. When people invest in how a project or ministry shaped, there will be perceived relevance.

Biblical foundation: One body, Many gifts (1 Cor 12)

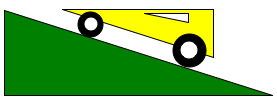

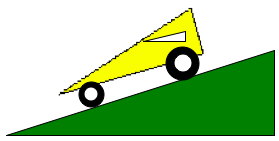

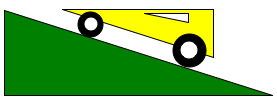

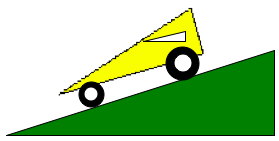

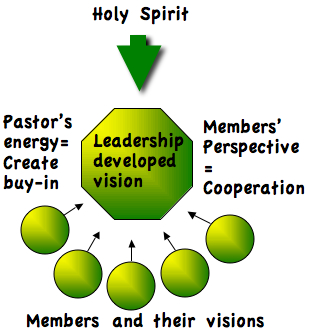

There is an unfortunate tendency with some leaders to assume that their responsibility is to make the decisions, while it is the responsibility of others to cooperate. That method is efficient and facilitates uncomplicated structural diagrams, but it does not resonate with the way human beings get involved in a common cause. Making a plan and getting people to cooperate is like pushing a car uphill – those pushing are exhausted, while the passengers are bored. However, developing a cooperative plan that reflects what is significant and important for all the participants, as expressed and developed by them, is like pushing a car downhill. There is soon momentum far out of proportion to the initial thrust, and the direction and results are often unexpected. But very few are bored.

There is an unfortunate tendency with some leaders to assume that their responsibility is to make the decisions, while it is the responsibility of others to cooperate. That method is efficient and facilitates uncomplicated structural diagrams, but it does not resonate with the way human beings get involved in a common cause. Making a plan and getting people to cooperate is like pushing a car uphill – those pushing are exhausted, while the passengers are bored. However, developing a cooperative plan that reflects what is significant and important for all the participants, as expressed and developed by them, is like pushing a car downhill. There is soon momentum far out of proportion to the initial thrust, and the direction and results are often unexpected. But very few are bored.

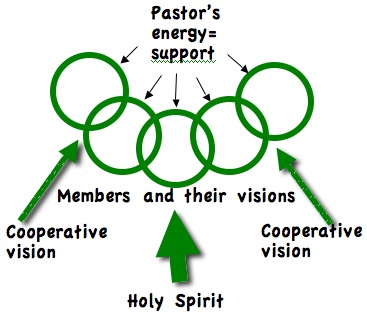

This method of engaging all participants so that they are driven by what is significant to and expressed by them is especially important for churches because of the particular dynamic laid out for us by Paul in 1 Cor 12. Using the analogy of a human body, Paul informs us that all believers have a coordinated role to play in building each other up. However, an important basis for the unity of the body is found in the individual connection of each person to the Holy Spirit (12:4). It is God who puts the body together (12:24). One implication of this teaching is that all believers can make a contribution to the mission and direction of the church based on what they have been given by the Spirit. The ministry task in which they become involved should be according to the concerns that God has placed in their hearts. When believers work together to shape the vision of the church in a way that is significant for and revealed through each individual, the result is commitment and ownership of the task.

This method of engaging all participants so that they are driven by what is significant to and expressed by them is especially important for churches because of the particular dynamic laid out for us by Paul in 1 Cor 12. Using the analogy of a human body, Paul informs us that all believers have a coordinated role to play in building each other up. However, an important basis for the unity of the body is found in the individual connection of each person to the Holy Spirit (12:4). It is God who puts the body together (12:24). One implication of this teaching is that all believers can make a contribution to the mission and direction of the church based on what they have been given by the Spirit. The ministry task in which they become involved should be according to the concerns that God has placed in their hearts. When believers work together to shape the vision of the church in a way that is significant for and revealed through each individual, the result is commitment and ownership of the task.

Navigational tool: Involve people in a decision making process

Rather than making decisions for people and asking them to come on board with our plans, good motivators involve the participants in a decision making process. What might this look like for a missions team that wants to involve the church more deeply in the missions efforts of the church? The following three motivational examples provide gentle, medium and major impacts to the church.

Rather than making decisions for people and asking them to come on board with our plans, good motivators involve the participants in a decision making process. What might this look like for a missions team that wants to involve the church more deeply in the missions efforts of the church? The following three motivational examples provide gentle, medium and major impacts to the church.

Gentle Impact: The Bucket vote

Some churches have a yearly special project chosen by the missions committee which the congregation supports financially. This praiseworthy practice can be adjusted so that it becomes a decision making process and draws people deeper into their commitment to missions.

Instead of presenting only one project, promote 5 suitable and worthwhile short term projects out of which the congregation can choose. In a suitable place, arrange information about each of the projects together with separate donation boxes (the “buckets”). Hand out, or place in the bulletin, $500 in play money in $100 notes and ask people to put the money towards the projects that they believe are the most impacting and worthwhile. They can spread the money around to as many as they like, or put the whole amount towards one project. The project that collects the most play money will be the one promoted that year.

Instead of presenting only one project, promote 5 suitable and worthwhile short term projects out of which the congregation can choose. In a suitable place, arrange information about each of the projects together with separate donation boxes (the “buckets”). Hand out, or place in the bulletin, $500 in play money in $100 notes and ask people to put the money towards the projects that they believe are the most impacting and worthwhile. They can spread the money around to as many as they like, or put the whole amount towards one project. The project that collects the most play money will be the one promoted that year.

This is not just a gimmick to draw people’s attention towards missions, but an application of motivational principles:

evaluate and prioritize … active participation … create buy-in

- It engages people in a decision making process by encouraging them to evaluate and prioritize. They need to think through why one particular project may be more strategic and important than another. This stimulates missiological questions: What values and principles should guide my choices when it comes to missions? Which project will provide the greatest impact for God’s kingdom?

- It promotes active participation. By putting in the play money into a bucket, people act out their commitment to a particular missions project. Making a decision to be involved in this exercise will likely translate into a level of commitment and ownership to the project itself.

- It creates buy-in. This is not an empty exercise because people’s choices count. Because they have been involved in a decision making process that produces results they have participated in, they will recognize the project chosen as the one that they voted for and will have a sense of ownership (assuming that it was their project that won). Thus, there is a development of emotional identification with something they have declared as significant and worthy of support.

Medium Impact: Find Advocates

A prayer meeting for missionaries was arranged. Prayer is significant and believers affirm the need to pray for missionaries. Yet, very few people participated. Can this be done differently, so that people are committed and involved? One church thought so.

A prayer meeting for missionaries was arranged. Prayer is significant and believers affirm the need to pray for missionaries. Yet, very few people participated. Can this be done differently, so that people are committed and involved? One church thought so.

Using the navigational tool of engaging people to make decisions, the missions committee stopped planning for people and assuming cooperation, and instead moved to planning with people. Rather than providing an opportunity to pray, they created a decision making process through which the nature and arrangement of prayer for missions was accomplished. First, missionaries were asked if they would be interested in having advocates in the church who would promote their ministry and interests. There was a 100% positive response. Then individuals in the congregation were approached and asked if they would consider becoming advocates for a missionary. All those willing to consider the possibility were invited to a workshop in which they advised, discussed and individually decided what being an advocate would mean for them.

another motivational principle: manage agreements (not people)

Agreements were then drawn up that corresponded to each advocate’s desire to participate. This step takes advantage of another motivational principle critical for volunteer organizations: it is much more relaxing and effective to manage agreements3, rather than trying to encourage cooperation with a job determined by someone else. These advocates now look for opportunities and create venues where the missionary’s task can be promoted for prayer according to the plan that they have established.

Major Impact: Follow the interests of the congregation

One pastor took advantage of this decision making dynamic by taking the time to discover where people in the congregation were already committed or interested in missions. Rather than promoting a missionary supported by the church and assuming people would cooperate, he started by discovering where people’s interest in missions lay. He took advantage of existing commitments and concerns and provided those people opportunity and encouragement to get others informed and involved.

One pastor took advantage of this decision making dynamic by taking the time to discover where people in the congregation were already committed or interested in missions. Rather than promoting a missionary supported by the church and assuming people would cooperate, he started by discovering where people’s interest in missions lay. He took advantage of existing commitments and concerns and provided those people opportunity and encouragement to get others informed and involved.

In a similar vein, another church initiated a decision making process through which teams were assigned who developed their own purpose and direction for missions. These teams grew out of individuals’ existing interest and involvement and took advantage of the momentum already in place. These teams were guided and challenged to “dream big.” Impact is now being felt both within the church and around the world. Two years ago the missions committee consisted of one dedicated man who corresponded with all the missionaries supported by the church. Recently, he joyfully informed me that there were now 50 people involved in a variety of ways and people are coming up to him asking, “How can I take part?” During one planning session, the senior pastor declared, “This is changing our church.”

For this level of transition and impact, coaching is recommended.

Getting people involved in a decision making process is not necessarily efficient, but use of this navigational tool can create dramatic changes. It is important for missions teams to remember that they are not just working on behalf of the church, but are also working to engage the church. Their role is to get the church involved in and excited about missions. Engaging the congregation in a decision making process whenever possible may be more complex and less controllable than decisions made during a committee meeting, but this process will pay dividends through increased commitment and a greater global impact.

Mark spends part of his time assisting churches in developing effective and impacting missions committees. If you are interested, please contact him via the Contact Me form. If you would like to leave a comment about this article, please use the “comment” link at the bottom of this article.

____________________

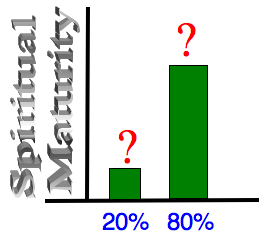

In my responsibility of providing outreach and missions resources to churches, I have come across a curious phenomenon. My experience is that there are a number of people in church leadership who do not have a positive view of the spiritual maturity and commitment of their congregation. Comments such as “a mile wide and an inch deep,” “20% do 80% of the work,” “half an hour after the sermon is over they don’t remember it, let alone apply it,” “they don’t take advantage of opportunities to go deeper,” and “they don’t know their Bibles” have been expressed in my hearing. Why this is curious is that my experience with the people of God in our churches has given me quite the opposite opinion. I have been constantly impressed, motivated and encouraged by the level of spiritual maturity and commitment to Christ in the people I meet.

In my responsibility of providing outreach and missions resources to churches, I have come across a curious phenomenon. My experience is that there are a number of people in church leadership who do not have a positive view of the spiritual maturity and commitment of their congregation. Comments such as “a mile wide and an inch deep,” “20% do 80% of the work,” “half an hour after the sermon is over they don’t remember it, let alone apply it,” “they don’t take advantage of opportunities to go deeper,” and “they don’t know their Bibles” have been expressed in my hearing. Why this is curious is that my experience with the people of God in our churches has given me quite the opposite opinion. I have been constantly impressed, motivated and encouraged by the level of spiritual maturity and commitment to Christ in the people I meet. I have an uncomfortable suspicion that a significant part of this negative view of congregations stems from an inadequate approach to ministry by the leadership. The average church organization, whether labeled traditional, seeker sensitive or missional, has a leadership-driven program which members of the church are encouraged to support. The response by the congregation tends to be less than expected, especially if support has been indicated by a congregational vote.

I have an uncomfortable suspicion that a significant part of this negative view of congregations stems from an inadequate approach to ministry by the leadership. The average church organization, whether labeled traditional, seeker sensitive or missional, has a leadership-driven program which members of the church are encouraged to support. The response by the congregation tends to be less than expected, especially if support has been indicated by a congregational vote. A couple of months ago, Karen and I proposed to our church

A couple of months ago, Karen and I proposed to our church  I do not see that people are asking, “What’s in it for me?” Instead, they want to know, “Why me?” This is not a self-serving question. It is a self-identifying, individual question.

I do not see that people are asking, “What’s in it for me?” Instead, they want to know, “Why me?” This is not a self-serving question. It is a self-identifying, individual question. He plays the essential part of empowering leaders to pursue their callings and passions. He strengthens others’ obedience by creating a culture where they can say yes to the Spirit…. [All] the ministries he told me about happened away from the church. This same pastor went on to say, “I wouldn’t have a clue how to do what they do.” The very thought that clergy could preside over these kingdom expressions is ludicrous. Yet many congregational leaders do not trust people to minister out of their sight. (140)

He plays the essential part of empowering leaders to pursue their callings and passions. He strengthens others’ obedience by creating a culture where they can say yes to the Spirit…. [All] the ministries he told me about happened away from the church. This same pastor went on to say, “I wouldn’t have a clue how to do what they do.” The very thought that clergy could preside over these kingdom expressions is ludicrous. Yet many congregational leaders do not trust people to minister out of their sight. (140) “Coaches help people.” Coaching is a relationship…, not a program. It is focused on the [believer], not the program. You coach a [believer], not his or her ministry….

“Coaches help people.” Coaching is a relationship…, not a program. It is focused on the [believer], not the program. You coach a [believer], not his or her ministry….