Responding to Theological concerns about Disciple Making Movements #2

Preamble:

Critics of Disciple Making Movements (DMM) have raised biblical and theological concerns about some DMM principles and practices (DMM P&Ps). Because Fellowship International (FI) has adopted and adapted DMM P&Ps with the desire to be used by God to catalyze kingdom growth around the world, such critiques should be taken seriously and answered with care. The previous article on Obedience-Based Discipleship (OBD), this article on Discovery Bible Study (DBS), and the following article on People of Peace (POP) attempt to address three significant critiques with the invitation to respond as we participate together in the missio Dei.

Theological concern: Discovery Bible Study (DBS)

Obedience-based discipleship (OBD) uses an inductive or discovery method of Bible reading where participants discern the meaning of a passage in a group setting through interactive engagement with a passage of Scripture. Usually, these groups follow some form of Discovery Bible Study (DBS) that uses a set of open-ended questions suitable for any passage of Scripture. For example, a core question is “What does this passage reveal about what God is like, what God wants, and what God is doing?” Each meeting is led by a facilitator who reads out the questions and encourages others to respond. The DBS process I prefer is available here.

Discovery methodology prioritizes the engagement of participants, both believers and seekers, to discern the meaning of a Bible passage rather than depending on the prepared explanation of a teacher. Three concerns raised by critics are that (1) people who do not have the Holy Spirit are guiding others in Bible study, (2) without appropriate spiritual oversight by a mature believer, participants will misunderstand or misapply Scripture, and (3) DBS displaces teaching and proclamation so that these spiritual gifts are not given appropriate biblical emphasis.

In response to these concerns, this article will

- Describe the three key issues found in public critiques of DBS,

- Affirm those convictions that are consistent with Fellowship International’s theology,

- Describe the DBS dynamic,

- Provide a summary explanation of how Fellowship International’s use of DBS is theologically consistent and appropriate,

- Introduce the theology and hermeneutic used in the discovery method, and

- Provide examples of how DBS is being used in missions along with reasons why these accord with the way God’s Spirit brings transformation.

A. Summary of the case against DBS

The following DBS critique is summarized from podcasts by Berger & DeMars and articles by Morell, Kocman and Vegas, and Rhodes’ book, No Shortcut to Success. Bibliographic information can be found in the list of references.

The use of this methodology as the primary disciple-making practice has drawn criticism for three reasons:

- Unbelieving facilitators: It is inappropriate for someone who is not a professing believer to facilitate a Bible study because they do not have the Spirit of God guiding them. This is unheard of in the New Testament. If DBS is the way people are discipled in DMM, then unconverted unbelievers are engaged in the process of making “disciples” and thus disciple-making movements are being encouraged where there is no conversion to the gospel.

- Lack of Spiritual Oversight: Related to the previous concern, but examined separately, is the practice of encouraging Bible study without the oversight of a mature believer. Such a practice is spiritually irresponsible because people can easily misunderstand or misapply Scripture.

- Disparagement of preaching and teaching: In DBS, discovery is emphasized while teaching and preaching are disparaged as “knowledge-based discipleship,” as if obedience can be separated from knowledge. The biblical pattern of evangelism is proclamation, not inductive Bible study. After Pentecost the apostles engage in preaching and teaching. They never promote the idea that believers, let alone unbelievers, should facilitate a self-corrected, untaught, Bible study. The biblical methodology is proclamation by Holy Spirit-appointed believers in whom the authority to teach rests. Historically Protestants hold that evangelism is carried out by the preaching of the gospel, not by the study of God’s Word by unbelievers.

B. Fellowship International affirmations of theology

- Unbelieving facilitators: Since teaching, prophesying, and evangelism are all described as gifts of the Spirit given for the building up of the church (Eph 4:11-16), it is inappropriate to appoint, promote, or encourage an unbeliever to take on the position and responsibility of teaching others the Bible and the message of the gospel.

- Lack of Spiritual Oversight: Mature believers should take seriously their responsibility to give guidance to seekers who are pursuing Jesus and to new believers who are learning how to live out their covenant with Jesus (1 Tim 4:11-13, 2 Tim 4:1-2, Tit 2:1-15). It is irresponsible to refuse, ignore or downplay such interaction and oversight.

- Disparagement of preaching and teaching: Since teaching, prophesying, and evangelism are all described as gifts of the Spirit given for the building up of the church (Eph 4:11-16), the proclamation and teaching of God’s Word is to be encouraged, not disparaged.

C. The DBS Dynamic

An understanding of the DBS dynamic is important for clarity before responding to the critiques.

DBS is a method of Bible reading, not teaching: The facilitator creates an environment for people to engage God’s Word directly so that all can discern together how the character, will, and mission of God are revealed in the text.

Discovery at the heart of disciple making: Fellowship International views the discovery method as the heart of disciple making because a deep and appropriate engagement with God’s Word brings transformation as people conform their lives to the revelation of God’s character, will, and mission. DBS emphasizes that the primary and authoritative source for the proclamation of the gospel and the teaching of who God is and what he wants is Scripture itself; God’s self-revelation is the foundation of a true relationship with God. The primary focus of DBS is that both believers and seekers will know how to read, interpret, and respond to God’s Word.

Facilitators not teachers: DBS facilitators are not teachers but participants who hold a posture of submission to God’s Word along with others, expecting a sacred message they can understand. A facilitator provides opportunity for God’s Spirit to act as the teacher rather than being the one to explain what the Bible means.

Anyone can facilitate. Because DBS is primarily a way to come to know God’s character, will, and mission by reading the Bible and discussing the implications, all group members are encouraged to take turns facilitating. This is as simple as following a one-page outline of instructions and questions.

DBS is a means for all believers to be disciple-makers: Fellowship International interprets the Great Commandment as applicable to all believers. Therefore, all believers are called to be disciple-makers and DBS is a clear process that any believer can use to engage interested people – seekers or believers – so that they have opportunity to reflect on what God has revealed. Not all believers can be teachers, but all can become disciple-making facilitators. Being a facilitator is not an authoritative position, but a method by which people are exposed to the Bible as God’s self-revelation.

DBS prioritizes the apostles’ teaching and proclamation: DBS is a simple, reproducible method of Bible reading that engages people directly with God’s Word rather than by removing the reader from the text by one degree through the filter of a human teacher.

The discovery process empowers participants to develop their theology: Since participants read God’s word primarily as God’s self-revelation, they are gaining a biblical understanding of who God is. The message in a passage of Scripture is not interpreted or claimed as a direct communication from God to the reader but as a revelation of God’s character, will, and mission. From that understanding, an appropriate application can be determined. See below for an introduction to the theology and hermeneutic of the discovery method.

DBS allows for intercultural catalyzing: Because people discover for themselves the meaning of God’s word, the cross-cultural worker does not need to cross the cultural bridge with their own understanding of God’s word; instead, they create access so that others can read God’s Word for themselves. This does not negate the need for language and cultural learning, but it provides a pathway into significant disciple-making engagement of God’s word even before the cross-cultural worker has mastered communication skills.

D. How Fellowship International’s use of DBS is biblically and theologically appropriate

Fellowship International believes that DBS is an appropriate and effective disciple-making practice for both believers and seekers because it is centered on God’s Word. The specific critiques mentioned above are now addressed:

1. Unbelieving facilitators: Some have expressed concern that DMM practitioners are encouraging people who are not yet committed followers of Jesus to take spiritual leadership within a Bible study. This would be in violation of the concern laid out in the pastoral letters that spiritual leaders be committed followers of Jesus (e.g., 1 Tim 4). Fellowship International affirms this concern. However, DBS, while an important disciple-making process, is primarily a Bible reading method suitable for anyone, whether believer or seeker. Furthermore, the facilitator is not considered a spiritual leader but a fellow participant, although the hope is that the person will become a committed believer and develop into a spiritual leader.

In FI’s DMM approach, all people whether believers, unbelievers, or seekers, are encouraged to read and engage God’s Word in any setting. The reading of God’s Word is always a good thing and should not be discouraged. The hope is that unbelievers will become seekers, seekers will become believers, and believers will be strengthened in their faith to become mature disciple-makers. In DBS, the authority of the message remains in God’s Word, not in the facilitators or participants. They are the recipients and the ones discovering what God has revealed. It is the Word alone that speaks authoritatively.

Because facilitation of DBS is a means of reading Scripture with others, it is appropriate for a non-believer to take on a facilitation role and everyone is encouraged to take their turn by following the DBS aims and questions. It is normal for one person to instigate the gathering of the group to guide and monitor the DBS process – referred to in this article as the “facilitator,” even though others are encouraged to facilitate during a meeting – but they do not have the authority of a teacher.

2. Lack of Spiritual Oversight: A key DMM principle is to multiply DBS groups among people who have the desire to discover God’s character, will, and mission by engaging Scripture. Establishing a new group requires someone capable of being a facilitator, either a believer who embraces Jesus’ command to be a disciple-maker or a seeker who wants to read the Bible with their friends or relatives. Where movements are happening, people are establishing their own groups (e.g., reading the Bible at home with their family) even without the instigation of a DMM practitioner.

The history of missions has been founded on God’s Word. A lack of oversight by mature believers should not be a reason to keep God’s Word from people hungry to learn. In many places, people are being exposed to God’s Word through technology that does not allow for oversight (internet, radio, Scripture distribution). While not ideal, such realities do cause us to rely on the Holy Spirit, especially when we are not able to follow up, like Philip and the Ethiopian Eunuch who continued alone back to his home country (Acts 8). DBS anticipates and provides for rapid distribution of the gospel message through a simple, reproducible method of reading to understand and obey that helps seekers understand how to engage God’s Word appropriately and with impact, even without oversight.

To make oversight the limiting factor for the spread of the gospel seems inappropriate in light of New Testament patterns. The apostle Paul expressed thanksgiving for the spread of the gospel (1 Thess 1:8-10), even when it was accomplished through those who were less than sincere (Php 1:15-18).

Nonetheless, in the normal course of catalyzing a disciple-making movement, the DBS process is instigated by a DMM practitioner who continues to monitor and debrief the primary facilitator of a group. This spiritual support and oversight allow the disciple-maker to gauge how the group is engaging God’s word, not by taking responsibility for the group, but through interaction with the facilitator. This approach requires a deep faith in God’s Word and confidence in the Holy Spirit to guide the process as the facilitator is encouraged and empowered. This not only aids the multiplication of groups who engage God’s Word, but also establishes a means for the intentional training, teaching, and disciple-making of facilitators. In addition, the disciple-maker can challenge facilitators concerning their own personal faith response. If a person has not yet made a commitment to Christ, that will be an essential part of the conversation.

3. Disparagement of preaching and teaching: Some have expressed concern that proclamation and teaching are discouraged in the DBS process, noting that the New Testament clearly describes proclamation and teaching as the primary ways people were introduced to the gospel. Three responses:

a. DBS is not a forum for teaching:

Fellowship International affirms the importance of teachers, prophets, and evangelists in the building up of the church and does not discourage or disparage such gifting. However, proclamation and teaching are discouraged in a DBS context because such actions undermine the discovery process that is essential to develop a conviction that anyone can read and interpret Scripture sufficiently in order to discover God’s character, will, and mission.

Preaching and teaching must be true to the authority of Scripture and DBS equips people by developing a familiarity with Scripture so they can engage and even evaluate a teacher’s message based on their understanding of God’s Word.

DBS can also be a welcome correction to an unhealthy dependence on preachers and teachers whose knowledge and competence encourage believers to become passive and rely on the insights of the teacher rather than exploring the Word for themselves. DBS mitigates the concern that people may come to faith with a desire for salvation but without a commitment to obey. Trusting the instruction and guidance of teachers rather than exploring Scripture in order to obey weakens the disciple. DBS begins with and maintains its focus to know God’s character and conform to his will and mission. “What you win them with is what you win them to.”

The claim that personal engagement of God’s Word through a discovery process is a legitimate priority for a disciple is based on the Protestant doctrine of the perspicuity of the Bible[1]. This doctrine assumes that God intended to communicate a message for all people through his prophets and apostles who were guided by the Holy Spirit in what they wrote, and that he was successful – 2 Tim 3:16-17, Heb 4:12. Thus, anyone who reads God’s word with care and sincerity can discern God’s message, especially in the self-correcting environment of a group. Through DBS people learn that they can read and discover God’s self-revelation with understanding and confidence. Rather than assuming a position between God’s Word and listeners in order to explain and interpret, facilitators together with all participants, submit themselves to the authority of Scripture. The Holy Spirit remains the teacher; the facilitator and the participants, are the learners.

At the same time, while personal engagement with God’s Word is necessary and foundational for disciples, it is not sufficient because the input of believers who can teach is also important. Such teachers are a gift from God to Christ’s body and are to be encouraged as they help others understand God’s Word and grow in their discipleship journey. Such teachers complement the personal engagement of God’s Word, but should not undermine or become a substitute for personal discovery.

b. DBS promotes direct engagement of the apostles’ proclamation and teaching:

Despite discouraging a teaching posture for DBS facilitators, DMM practitioners encourage people to engage the record of proclamation and teaching in the New Testament. At the time of the book of Acts, proclamation was necessary for people to hear the gospel because the New Testament was not yet written or collated. The New Testament was written by the apostles through the prompting of the Holy Spirit to expand the proclamation of the gospel beyond verbal messages to written text. Reading the Bible is therefore a form of hearing Jesus’ and the apostles’ proclamation and teaching. DBS, therefore, does not downplay proclamation and teaching; it is exposing participants to a God-given, inspired means of proclamation and teaching found in the text itself.

There is much to be learned from other believers about the way of Jesus and how to live in the kingdom of God, and apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds, and teachers (APEST – Eph 4:11-12) are all gifts to the church for this purpose. We must never quench the Spirit by discouraging those to whom God has given these gifts but give them full scope to fulfill the task God has called them to. A fuller and deeper engagement of God’s Word is gained through the supplementary gifts of preaching and teaching, as long they enhance and do not undermine the primary engagement of Jesus’ and the apostles’ teaching through a discovery process.

c. DBS prioritizes disciple-making over passive listening:

All believers are called to be disciple-makers who make disciple-makers (Mt 28:19-20). This responsibility is effectively carried out in a group setting through a discovery process as participants work out the meaning of God’s message and its implication for their lives. This follows the pattern evident after Pentecost when believers “devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching” (Acts 2:42) and were often “together” (Acts 2:44,46) for fellowship and worship. The testimony that the “Lord added to their group others who were being saved” (Acts 2:47) likely implies that seekers joined with believers to engage that teaching. Furthermore, the apostles often addressed the whole church in their epistles (e.g., 1 Thess 1:1) indicating that all believers were expected to engage the apostles’ teaching directly, not just through the authority of a local leader. Engaging the apostles’ message in our time occurs first through such readings of the New Testament as DBS offers.

While DBS provides a foundational pathway by which seekers can become disciples and believers can be strengthened in their faith and become involved in making disciples, this process does not displace preachers and teachers within the body of Christ. Rather, it emphasizes the priority of Scripture reading that needs to be complemented and supplemented by the guidance of Spirit-filled believers whom God appoints for such ministry. The discovery process is how disciples are made and the responsibility for this task is not limited to those with APEST gifts.

E. An introduction to the theology and hermeneutic of the discovery method

DBS promotes an important hermeneutic: the Bible as revelation. The Bible is an authentic, necessary, and sufficient revelation of God’s character, God’s will, and God’s mission within cultural, historical, and geographical contexts that are different from the contexts of today’s readers. The Bible also provides an authentic, necessary, and sufficient representation of humanity and the human condition described within diverse cultural, historical, and geographical contexts. Both unfamiliarity with the biblical contexts and the inevitable influence of the reader’s personal worldview and cultural assumptions challenge the ability of the reader to interpret and apply Scripture. These challenges indicate that to understand the text the reader needs (1) familiarity with the Bible, (2) community support to interpret and apply God’s Word, and (3) teachers and scholars.

The role of DBS is to (1) expose people to God’s Word, (2) guide people to read God’s Word as his self-revelation, (3) help people read the Bible with understanding and confidence, (4) ensure that the Bible is read in community, and (5) challenge participants to respond to what they have discovered. DBS demonstrates a high reliance on the perspicuity of the Bible, the work of the Holy Spirit, and a community of believers and seekers. When the discovery process happens regularly over time an ever-increasing familiarity with Scripture is developed.

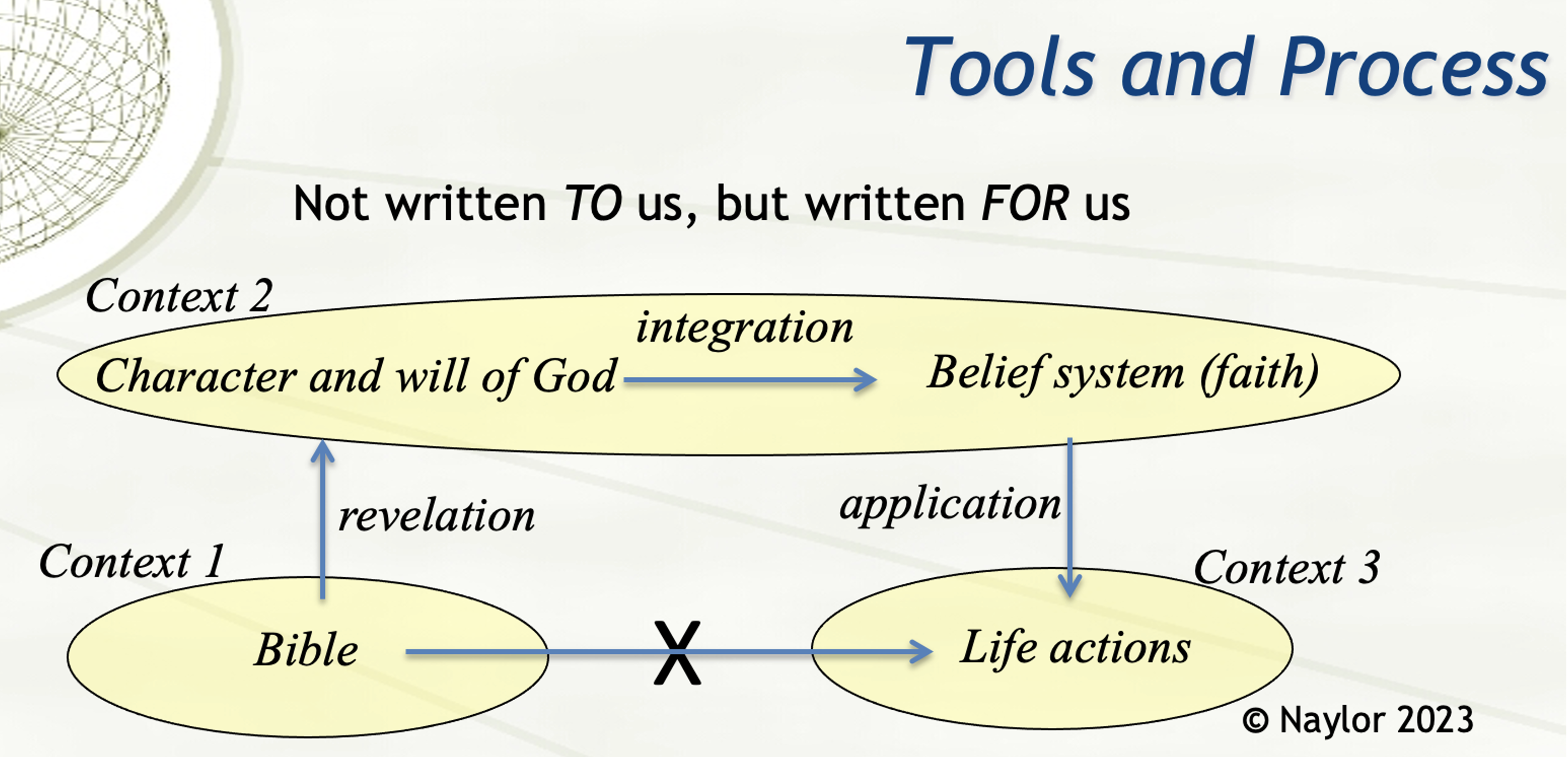

The following diagram shows the interpretive process used by DBS:

The Bible is not read in order to find a direct application to life as if contextual interpretation is not needed (bottom arrow). At least two cultural contexts need to be considered: the biblical culture and our own culture. Because of this reality, a direct connection between the Bible and our situation is not possible. Instead, Scripture is viewed as the revelation of God given in another time and place and through a different cultural lens (left arrow). The discernment of God’s revelation in a passage then shapes our beliefs as we integrate the revelation into our theology and belief system (top arrow). Only then does that belief find application as it is expressed through culturally appropriate actions (right arrow).

DBS encourages respect for and integrity with God’s Word as authoritative because the participants read and understand the meaning of a biblical text rather than using a variety of texts to support a particular doctrine. At the same time, readers in a group context are guided to self-contextualize the revelation of God as they explore how these truths can be expressed in their lives. This is a foundational practice for any congregation to become the hermeneutic of the gospel (Newbigin 1989:222) and so moves the group towards a self-identification of “church.” At the same time, this practice does not exclude contextualization of the gospel by outsiders, nor does it undermine or exclude God’s gift of apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds, and teachers (APEST). DBS allows the text to reveal God to seekers and to empower believers so that they have confidence in what they read, and it demonstrates a crucial process for how to use God’s Word to assess the truth claims of those who teach so that they are not led astray.

F. Examples of how DBS is being used in missions along with reasons why these accord with the way that God’s Spirit brings transformation.

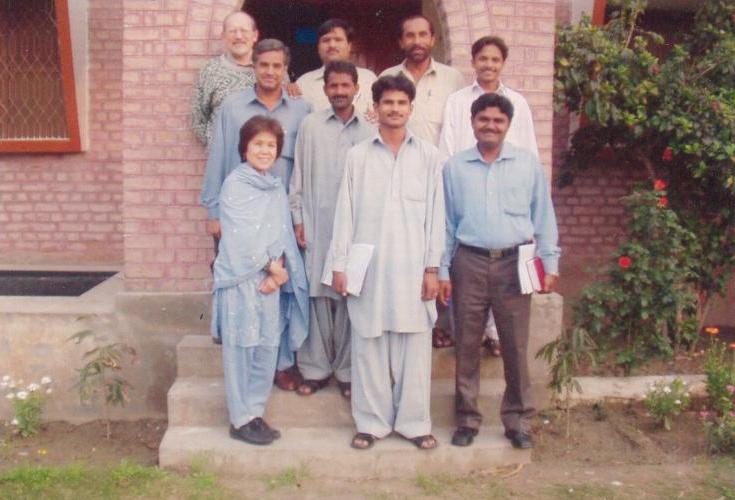

A DBS Case Study in Pakistan

Papu is a believer in Pakistan from a Hindu background whom I am coaching according to DMM P&Ps. He has 13 men from different villages that he calls People of Peace (POPs). Four are baptized believers, the rest are seekers from a Hindu background who are learning about who Jesus is and what God’s Word teaches. On Sundays they meet as a group. During the time together Papu engages them in a discovery process of Bible reading. He teaches a story to the illiterate men based on a passage of Scripture that is read by the literate men. The men take turns repeating the Bible story until everyone repeats it adequately. Papu and the POPs then go through a set of DBS questions to work out the meaning and significance of the story followed by a challenge to respond in a manner that fits with what they have discovered about the character, will, and mission of God. These questions are always the same, allowing for this process to be repeated with any Bible story or passage, and for the men to repeat the process when they return to their villages.

During the week each of the men is required to repeat the story or read the passage with their family and/or friends, ask the DBS questions, and then challenge the group members to respond. Papu visits the villages of his POPs and oversees their efforts to guide others in a discovery reading of God’s Word. These facilitators are not training to be teachers; they are like the woman at the well (Jn 4) telling people in their village what Jesus has said. The goal for the people of Sychar was not to continue learning from the woman but to turn to Jesus and learn from him. Similarly, the POPs point to Scripture so that people can hear God speak and then learn to respond.

DBS and Bible Translation

As a Bible translator, I am intrigued by the history of Bible translation and the stories of the opposition and struggle faced by those who sought to provide the average person access to God’s Word in their own language. In session three of the documentary series, The Adventure of English, the presenter explains how the Bible came to be translated into vernacular English.

At the time of William Tyndale, a Latin translation, which people could not understand, was the Bible of the church. During worship services, the priest would read passages silently so that the ordinary people would not hear, and a bell would sound to let them know when the reading was complete. The Bible was considered too sacred for their ears.

Meanwhile, outside the ornate cathedrals, people were entertained by mystery plays, similar to children’s advent plays today, that were loose portrayals of Bible stories, performed in the vernacular English. These were entertaining but poor reflections of the biblical text.

It was in this context that Tyndale envisioned and worked towards an English translation of the Bible from the original languages[2]. When a Bishop argued that it was harmful for people to have God’s law, Tyndale responded, “If God spares my life, in a few years a plowboy shall know more of the Scriptures than you do” (Brandon 2016).

Once the translation was complete, a group called Lollards who were dedicated to the reformation of Western Christianity, traveled around England secretly distributing handwritten copies of the English Bible at risk of imprisonment and execution. This conviction to give the Bible into the hands of the common person, written in their mother tongue, has been a key commitment of missionaries throughout the era of modern missions. The Gideons movement is an example of the conviction that the Bible should be made available to all so that anyone can read God’s Word for themselves.

Getting the Bible into the hands and thoughts of the average person drives DBS and is based on the belief that the foundational method for the proclamation and teaching of the gospel is God’s Word itself. Familiarity with and love for God’s Word cultivated through DBS ensures that the primacy of Scripture is established from the beginning of the seeker’s journey and that the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ remains the believer’s supreme teacher (Mt 23:10).

DBS and Bible Correspondence Courses

The Pakistan Bible Correspondence School (PBCS) invites Muslims to study the Bible. A series of lessons are sent out that consist of Bible passages and simple questions. Early on in my ministry I studied one series to help me learn the Sindhi language and religious vocabulary (I even received a certificate!). Whenever a person signs up to study the lessons, they are sent a copy of the Sindhi New Testament with the hope that they will read it, perhaps even together with family or friends. The basic introduction of the courses is supplemented by the staff of PBCS who travel to meet students, engage their questions, and give further teaching. One of their tools is DBS as they encourage seekers to effectively engage and respond to the good news of Jesus Christ.

The point of these illustrations is to demonstrate that DBS is being used as an effective and appropriate Bible reading tool for seekers and believers alike.

Conclusion

There is a claim that we remember 10% of what we read, 20% of what we hear, 30% of what we see, 50% of what we see and hear, 70% of what we discuss with others, 80% of what we personally experience, 95% of what we teach others (Dale, We Remember). Whether or not these percentages are accurate, the concept resonates. The more we engage God’s Word with others in order to understand and obey, the more we will retain and the greater the impact will be. DBS lays out some foundational practices for the sincere disciple who desires to follow Jesus fully. It is only one methodology and it is not sufficient for the building up the body of Christ. Leaders, pastors, and teachers are needed. What DBS provides is a foundational and impacting process through which disciples are made and who then know how to go on to become disciple-makers themselves. The goal is to adopt, adapt, and supplement such methodologies so that the body of Christ will be built up and there will be a missional impact of disciple-makers making disciple-makers.

Footnotes:

[1] Brackett (2010) informs us that both the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith and the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith state, “…Those things which are necessary to be known, believed, and observed, for salvation, are so clearly propounded and opened in some place of Scripture or other, that not only the learned, but the unlearned, in a due use of the ordinary means, may attain unto a sufficient understanding of them.” On p. 37 footnote 5 Brackett provides a list of the eight key points of the doctrine.

[2] John Wycliffe had translated the Latin Bible into English more than a century earlier. That translation had been outlawed in England (Wycliffe Bible Translators).

List of References

The Adventure Of English – Episode 3 The Battle for the Language of the Bible – BBC Documentary.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cZR1EXGapc&list=PLbBvyau8q9v4hcgNYBp4LCyhMHSyq-lhe&index=3

Berger, Russell & DeMars, Sean (2021). Episode 63: Obedience-Based Discipleship: Is it Biblical? Defend and Confirm Podcast. https://www.podbean.com/site/EpisodeDownload/PB112062DRUZ3N

Brackett, Kristian (2010) “The Perspicuity of the Scriptures: Presupposition, Principle or Phantasm” in KAIROS – Evangelical Journal of Theology, Vol. IV. No. 1, pp. 31-50

https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/81840#:~:text=The%20Perspicuity%20of%20Scriptu%2D%20re,Bible%20may%20find%20in%20some

Brandon, Steve (2016). The Plowboy. https://enjoyinghisgrace.wordpress.com/2016/01/27/the-plow-boy/

Dale, Edgar. We Remember. https://uh.edu/~dsocs3/wisdom/wisdom/we_remember.pdf

Kocman, Alex (2021). Is ‘Obedience-Based Discipleship’ Biblical? https://www.abwe.org/blog/obedience-based-discipleship-biblical

Morell, Caleb (2019); Book Review: The Kingdom Unleashed, by Jerry Trousdale and Glenn Sunshine.

https://www.9marks.org/review/book-review-the-kingdom-unleashed-by-jerry-trousdale-and-glenn-sunshine/

Newbigin, Lesslie (1989). The Gospel in a Pluralist Society. Grand Rapids: Eerdmanns.

Rhodes, Matt (2022). No Shortcut to Success: A Manifesto for Modern Missions. Wheaton: Crossway.

Vegas, Chad (2018). A Brief Guide to DMM.

https://radiusinternational.org/a-brief-guide-to-dmm/

“William Tyndale: A Master Translator.” Wycliffe Bible Translators. https://wycliffe.org.uk/story/william-tyndale?gclid=CjwKCAjw5MOlBhBTEiwAAJ8e1nAJ16UKZvMkSmzJ-LbpXz4bPRayytra9IJCNEM4tYbrBKEYITCpDhoCh4cQAvD_BwE

Additional resources related to DMM controversies

Coles, David (2022) Book Review: Matt Rhodes, No Shortcut to Success: A Manifesto for Modern Mission

http://ojs.globalmissiology.org/index.php/english/article/view/2662

___________ (2021) Addressing Theological and Missiological Objections to CPM/DMM in Motus Dei: The Movement of God to Disciple the Nations. Ed. Warrick Farah. Littleton: Wm Carey Pub.

Jolley, Ken (2020) 111. Exploring Vegas’ Critique of DMM. https://impact.nbseminary.com/exploring-vegas-critique-of-dmm/

Naylor, Mark (2020). 109. Defending DMMs: A response to Chad Vegas. https://impact.nbseminary.com/109-defending-dmms/

___________(2020). 110. Response to Stiles’ Critique of DMMs. https://impact.nbseminary.com/110-response-to-stiles-critique-of-dmms/

___________(2020). 112. DMM Critiques addressed at FI Summit 2020. https://impact.nbseminary.com/dmm-critiques-addressed-at-fi-summit-2020/

___________(2021). 114. Does DMM suffer from NA pragmatic arrogance?https://impact.nbseminary.com/114-does-dmm-suffer-from-na-pragmatic-arrogance/

Watson, David L. & Watson, Paul D. (2014). Contagious Disciple Making: Leading Others on a Journey of Discovery. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

Waterman L.D. (2019). A Straw Man Argument to Prove What God Shouldn’t Do: A Critique of Chad Vegas’ “A Brief Guide to DMM”

http://btdnetwork.org/a-straw-man-argument-to-prove-what-god-shouldnt-do-a-critique-of-chad-vegas-a-brief-guide-to-dmm/

Yinger, Ken (2020) 113. We are all Heretics,

https://impact.nbseminary.com/we-are-all-heretics/

I recently gave a message from the book of Ruth focusing on the meaning of the Hebrew concept of go’el, the “kinsman–redeemer” (NIV), which is one of the key themes of the book. While struggling to find the best way to communicate the reality that the meaning of the term is dependent upon the underlying cultural context, I realized that a comparison of Bible versions provided a means to that end, while also revealing the difficulties of the task of Bible translation. The diversity between the translations also underscores the importance of comparing translations when studying the Bible in order to come to a fuller understanding. The translations used are Today’s New International Version (TNIV), Today’s English Version (TEV) and the English Standard Version (ESV). Exegetical and cultural analysis is used to demonstrate how the underlying context determines the meaning of the verse. The examples also serve to illustrate the contrast between the translation principles used by these versions.

I recently gave a message from the book of Ruth focusing on the meaning of the Hebrew concept of go’el, the “kinsman–redeemer” (NIV), which is one of the key themes of the book. While struggling to find the best way to communicate the reality that the meaning of the term is dependent upon the underlying cultural context, I realized that a comparison of Bible versions provided a means to that end, while also revealing the difficulties of the task of Bible translation. The diversity between the translations also underscores the importance of comparing translations when studying the Bible in order to come to a fuller understanding. The translations used are Today’s New International Version (TNIV), Today’s English Version (TEV) and the English Standard Version (ESV). Exegetical and cultural analysis is used to demonstrate how the underlying context determines the meaning of the verse. The examples also serve to illustrate the contrast between the translation principles used by these versions. In this verse, the ESV and the TNIV have chosen different vowel markings to determine the translation of “wings” or “garment.”

In this verse, the ESV and the TNIV have chosen different vowel markings to determine the translation of “wings” or “garment.” The term translated as “family guardian” (TNIV), “close relative” (TEV) or “redeemer” (ESV) proved to be an extremely difficult concept to represent in our Sindhi Bible translation, and we spent hours trying to shape the text in a way that would do it justice. The problem is that this concept is absent in both Sindhi and English cultures. No one word or phrase can carry the weight of meaning represented by four Hebrew letters (go’el). Furthermore, the meaning of the word is, as with the examples above, revealed only through an understanding of the cultural dynamic. The male members of the Israelite community of that time had all the rights and powers. Even as the branches of a tree only remain green when attached to the trunk, so women and children were totally dependent upon the patriarch of the family. Only the patriarch had the power to rescue the female members of the family and raise them to a position of honor and security. This function of the patriarch was so crucial to the life of the Israelites that they had a separate term (go’el) to describe it.

The term translated as “family guardian” (TNIV), “close relative” (TEV) or “redeemer” (ESV) proved to be an extremely difficult concept to represent in our Sindhi Bible translation, and we spent hours trying to shape the text in a way that would do it justice. The problem is that this concept is absent in both Sindhi and English cultures. No one word or phrase can carry the weight of meaning represented by four Hebrew letters (go’el). Furthermore, the meaning of the word is, as with the examples above, revealed only through an understanding of the cultural dynamic. The male members of the Israelite community of that time had all the rights and powers. Even as the branches of a tree only remain green when attached to the trunk, so women and children were totally dependent upon the patriarch of the family. Only the patriarch had the power to rescue the female members of the family and raise them to a position of honor and security. This function of the patriarch was so crucial to the life of the Israelites that they had a separate term (go’el) to describe it.

When our main translator walked into the translation office last December in Shikarpur, Pakistan, I greeted him with, “I have a problem with heaven.” He laughed and responded, “Well, if you have trouble with heaven, what’s left? There is not much more to hope for!” I explained that it was not the concept of heaven that bothered me, but the terms used in our Sindhi Bible translation.

When our main translator walked into the translation office last December in Shikarpur, Pakistan, I greeted him with, “I have a problem with heaven.” He laughed and responded, “Well, if you have trouble with heaven, what’s left? There is not much more to hope for!” I explained that it was not the concept of heaven that bothered me, but the terms used in our Sindhi Bible translation. Moreover, when pre-existing teaching within the Sindhi community parallels biblical teaching, it is a cause for rejoicing. Not only is the task of translation made easier, but such teaching acts a bridge for the truth of God’s word. When Sufi teaching is assumed true by the Sindhi reader and similar teaching is encountered in the New Testament, the result is an affirmation of the truth of God’s word and encouragement to trust the NT.

Moreover, when pre-existing teaching within the Sindhi community parallels biblical teaching, it is a cause for rejoicing. Not only is the task of translation made easier, but such teaching acts a bridge for the truth of God’s word. When Sufi teaching is assumed true by the Sindhi reader and similar teaching is encountered in the New Testament, the result is an affirmation of the truth of God’s word and encouragement to trust the NT.