NOTE: Articles 90 – 93 on Navigational tools for Church Missions have been revised and incorporated into a single article through Catalyst Services.

The transitions and tools described in this series of articles are used as the framework for missions coaching among Fellowship churches in Canada. If you are interested in exploring a coaching relationship for your church’s missions efforts, please contact Mark via the contact link below.

This article elaborates on the first transition for church missions teams1 introduced in Navigational tools for missions.

Transition 1: From a geographical to a strategic people group emphasis

Navigational tool: Identify significant activities

Biblical foundation for the unchanging reference point: Acts 13 paradigm and the Acts 1:8 portfolio

“My frustration,” said Tom, slamming his hand on the table, “is now that ‘North America is a mission field,’ and ‘missions is from everywhere to everywhere’ and we are ‘all supposed to be missionaries,’ there are no boundaries for what we call missions. Our task is too broad and undefined. How are we supposed to know what we are responsible for?”

Mariam responded, “But God’s mission includes everything he is accomplishing in the world. Shouldn’t we have a part in whatever God is doing?”

“But we can’t do it all, so how do we decide which part?” Tom countered. “And shouldn’t there be a distinction between missions and local outreach? Look at the items under the missions portion of our church budget. We support camps, church planting, chaplaincy, short term missions teams…. We even have a donation to our denomination head office. It seems to me that Stephen Neill is right, ‘[when] everything is missions, then nothing is missions.’2”

“At the same time,” Guljan interjected, “There is a general feeling in the church that you have to travel somewhere else to call it ‘missions.’ It’s not a short term missions trip unless you have to get a visa! I feel like there is a breakdown of the traditional boundaries of missions, but what now? How do we determine the extent of our responsibilities as a church missions team? What belongs under the ‘missions’ heading and what shouldn’t be considered missions? How do we know when to say ‘no’?”

some have clung to their traditional role … others … feel overwhelmed

In the past, church missions teams often operated according to a simple pattern. Their role was to act on behalf of the church to provide a connection with missionaries who went to other countries for years at a time. Due to a number of impacting global changes –immigration, the rise of third world missions, an increasing awareness that North America is also part of God’s mission, and the rise of “hands-on” local church involvement through short term missions trips, to name a few – the intersection of missions with the church has shifted significantly. An inability to adjust to these changes has left many missions teams frustrated and confused. In reaction, some have clung to their traditional role defined by geographical boundaries and have failed to take advantage of the new opportunities. Alternatively, others have welcomed the new opportunities and pushed aside the old “maps,” but now feel overwhelmed by the options and the demands being made upon them. They are facing the new and exciting possibilities for participation in missions without adequate parameters to define the limits of their responsibilities. This reality has paralyzed some missions teams into being reactive, responding to needs presented to them whether or not those tasks should be regarded as missions.

Mary and Joe,3 a retired couple, had a fantastic vacation in a Latin American country. While there, they fell in love with the children at a local church. They noticed that there was no Sunday School, and so they offered to teach the children. They felt so fulfilled with this ministry that they decided to live there for a year and continue teaching the children. They approached their home church in Canada and asked the missions team for support. The couple is greatly loved by the congregation, but is this a strategic use of missions funds? On what basis should the missions team decide if they should respond positively to this request?

A local ministry had initiated a program without adequate funding. In desperation, the leaders wrote to supporting churches for help since they were now in debt with bills to pay. The missions chair read the letter to the team. “Why should we be responsible for their lack of planning?” grumbled one member. “How about we send a token amount?” suggested another. An amount was agreed upon, but the dissatisfaction with this reactive way of responding remained.

A local ministry had initiated a program without adequate funding. In desperation, the leaders wrote to supporting churches for help since they were now in debt with bills to pay. The missions chair read the letter to the team. “Why should we be responsible for their lack of planning?” grumbled one member. “How about we send a token amount?” suggested another. An amount was agreed upon, but the dissatisfaction with this reactive way of responding remained.

Church mission teams recognize the challenges brought about by the global changes, but many are unable to respond in a satisfying manner. The tidy framework of support and prayer for missionaries traveling to foreign lands to preach the gospel has become unraveled through the emergence of many other expressions of potential missions activities. In some cases, these activities are put on the agenda of the missions team without serious consideration of their legitimacy for the missions task. Very often, the team has neither the authority nor the tools to be appropriately discriminating in facing these challenges. The default mode has been to defer to the appeals of missions agencies or the vision of individuals connected to the church. How can a missions team function effectively in light of these demands?

Sorting the puzzle

Imagine taking 5 different puzzles, mixing them together and then trying to assemble them without using the original photos provided to guide you. You know that something should make sense, but the pieces don’t fit together properly. There is no “big picture” to guide your decisions and so you rely on intuition and guesswork, which quickly leads to frustration. Furthermore, sticking with one simple, tried and true method of assembling the pieces doesn’t help because you are presented with a number of different options that just don’t seem to fit together.

Imagine taking 5 different puzzles, mixing them together and then trying to assemble them without using the original photos provided to guide you. You know that something should make sense, but the pieces don’t fit together properly. There is no “big picture” to guide your decisions and so you rely on intuition and guesswork, which quickly leads to frustration. Furthermore, sticking with one simple, tried and true method of assembling the pieces doesn’t help because you are presented with a number of different options that just don’t seem to fit together.

In order to resolve this dilemma, two steps are required: a clear vision of the end product and a means to get there.

The vision for the puzzles is found in the original photos. With respect to missions, those “original photos” are a metaphor for a clear understanding of God’s mission (the unchanging reference point). This focus on God’s mission as the unchanging reference point in our missions endeavors is not a new concept and has been examined extensively.4

The vision for the puzzles is found in the original photos. With respect to missions, those “original photos” are a metaphor for a clear understanding of God’s mission (the unchanging reference point). This focus on God’s mission as the unchanging reference point in our missions endeavors is not a new concept and has been examined extensively.4

But further guidance is needed: a means to sort out the puzzle pieces in order to match the original photos is also required. This is equivalent to the “navigational tool” proposed below that will allow missions teams to use God’s mission as their “north star” to establish a discerning, proactive stance towards their ministry.

We will first provide a perspective on God’s mission, followed by a navigational tool that can be used by a missions team to align themselves to God’s purposes.

A Glance at a Biblical Basis of Missions (the unchanging reference point)5

In Acts 13:1-2, the church at Antioch, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, sent Barnabas and Paul away to accomplish a special work. It is both the “sending” aspect as well as the nature of the “work” that has defined the modern missions movement in the last few centuries.6 Suppose that one week after the departure of Barnabas and Paul, a deacon from the Antioch church happened upon the two men at a cross-roads in Antioch where they had opened a soup kitchen. He would have been shocked. “We sent you away,” he would have said. “Your job was to proclaim the gospel where the church cannot. In this city, it is the church’s job to proclaim the gospel. We sent you to preach the gospel to those who have not heard.” Fortunately, this did not happen, and the actions of Paul and Barnabas were in tune with the desire of the church and the moving of the Holy Spirit. The lessons learned from their ministry formed the basis for the modern missions movement:

In Acts 13:1-2, the church at Antioch, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, sent Barnabas and Paul away to accomplish a special work. It is both the “sending” aspect as well as the nature of the “work” that has defined the modern missions movement in the last few centuries.6 Suppose that one week after the departure of Barnabas and Paul, a deacon from the Antioch church happened upon the two men at a cross-roads in Antioch where they had opened a soup kitchen. He would have been shocked. “We sent you away,” he would have said. “Your job was to proclaim the gospel where the church cannot. In this city, it is the church’s job to proclaim the gospel. We sent you to preach the gospel to those who have not heard.” Fortunately, this did not happen, and the actions of Paul and Barnabas were in tune with the desire of the church and the moving of the Holy Spirit. The lessons learned from their ministry formed the basis for the modern missions movement:

- They went where the gospel was not being preached (crossing new barriers).

- They did the work that the sending church could not do (proclaiming beyond the church’s reach).

These priorities are clear from Paul’s ministry. He declared that he did not want to “build on someone else’s foundation” (Rom 15:20), and whenever a church was planted in a particular region, he considered his work completed and he moved on. Why? Because it is the role of the newly established church to be a witness to Christ in their area. Paul’s apostolic (= being sent) ministry was to go where the gospel was not being preached and do work that was beyond the reach of the established churches.

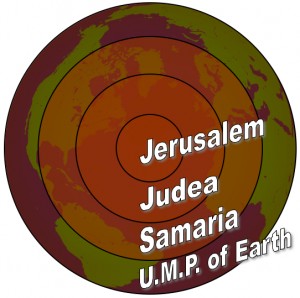

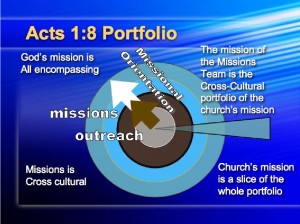

Acts 1:8 provides further clarification of the relationship of missions to the local church. The geographical descriptions of Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria and the ends of earth have commonly, and helpfully, been understood as a “portfolio” of involvement for the local church.7 Seen as a series of concentric rings, the first two, Jerusalem and Judea, can represent the evangelism work of the local church, and the third and fourth rings, Samaria and the ends of the earth, correspond to the sending work of the church, i.e., missions. In this scenario, “Samaria” represents people groups in which the church has been established and “Ends of the Earth” refers to unreached people groups.

Acts 1:8 provides further clarification of the relationship of missions to the local church. The geographical descriptions of Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria and the ends of earth have commonly, and helpfully, been understood as a “portfolio” of involvement for the local church.7 Seen as a series of concentric rings, the first two, Jerusalem and Judea, can represent the evangelism work of the local church, and the third and fourth rings, Samaria and the ends of the earth, correspond to the sending work of the church, i.e., missions. In this scenario, “Samaria” represents people groups in which the church has been established and “Ends of the Earth” refers to unreached people groups.

The discerning reader will remember that this transition was supposed to be away from a geographical focus. Instead the Acts 1:8 and the concentric rings appear to emphasize the geographical. However, even though geography is one barrier, it is not the fundamental concern. God’s concern for people and the lengths that he is willing to go in order to provide redemption indicates that the issue is not merely geography (an understandable emphasis before the impact of globalization), but any and all barriers that separate people from God’s salvation in Christ. God is a missionary God who overcomes barriers. Physical distance has been the most obvious barrier in the past, but it not the most significant one. It was through the leadership of McGavran and Townsend in the first half of the 20th century, that the more important aspects of cultural identity and the heart language of a people group began to be highlighted in missions. Although recognized throughout history, the need to cross these boundaries in order to engage people on their terms and make a gospel impact did not become a strategic focus in evangelical missions discussions until that time. It is far more difficult to become competent in these areas than to merely span geographical distance.

The discerning reader will remember that this transition was supposed to be away from a geographical focus. Instead the Acts 1:8 and the concentric rings appear to emphasize the geographical. However, even though geography is one barrier, it is not the fundamental concern. God’s concern for people and the lengths that he is willing to go in order to provide redemption indicates that the issue is not merely geography (an understandable emphasis before the impact of globalization), but any and all barriers that separate people from God’s salvation in Christ. God is a missionary God who overcomes barriers. Physical distance has been the most obvious barrier in the past, but it not the most significant one. It was through the leadership of McGavran and Townsend in the first half of the 20th century, that the more important aspects of cultural identity and the heart language of a people group began to be highlighted in missions. Although recognized throughout history, the need to cross these boundaries in order to engage people on their terms and make a gospel impact did not become a strategic focus in evangelical missions discussions until that time. It is far more difficult to become competent in these areas than to merely span geographical distance.

Furthermore, the expressed concern in the Bible as it reveals God’s mission is not geographical distance but the separation between the “nations” (e.g., Mt 28:19-20: “make disciples of all nations”).8 The term “nations” refers to distinct people groups, underscoring their unique linguistic, cultural and historical identities. These are the primary barriers irrespective of geographical location. Thus, the sending aspect of missions remains, but with a recognition that the criteria to determine what constitutes “missions” are primarily cultural rather than geographical.

Navigational Tool: Identify Significant Activities

Admittedly, this overview of the basis of missions provides only the broadest of brush strokes, but I have found it sufficient so that churches can refocus their missions efforts with a sense of connecting to God’s purposes. Based on this perspective, the following four part navigational tool can be used by missions teams to identify those significant activities that will align their activities to God’s mission:9

Admittedly, this overview of the basis of missions provides only the broadest of brush strokes, but I have found it sufficient so that churches can refocus their missions efforts with a sense of connecting to God’s purposes. Based on this perspective, the following four part navigational tool can be used by missions teams to identify those significant activities that will align their activities to God’s mission:9

For an activity to be a significant and strategic part of missions (as commonly understood by the modern missions movement), it must include:

- A clear connection to the establishment of the kingdom of God

- A “sending” that crosses cultural boundaries

- A strategic task with a gospel focus that the local believers cannot do.

- A concern for people groups (the “nations”)

Use this navigational tool to take action –

Use this navigational tool to take action –

A clear connection to the establishment of the kingdom of God: Adopt the Acts 1:8 portfolio as a paradigm for the church. The church’s portfolio then becomes a “slice” of God’s mission to the world. The inner two circles refer to local outreach where the church is directly involved. The outer sections provide boundaries that limit and clarify the focus of the missions team – cross-cultural activity requiring “sending” beyond normal local involvement of the congregation. It is paradoxical, but true, that creativity and enthusiasm abounds where there are clear limits to a task, together with freedom within those limits for the participants to choose their own course.

A “sending” that crosses cultural boundaries: Ensure that any missions effort includes a “sending” or commissioning aspect to a task beyond the direct responsibility of the church. This concern underscores the need for cross-cultural workers to have training that meets the demands of the task and that they develop key relationships so that they may function effectively in another cultural setting. The importance of taking part in God’s mission is underscored when commitments are taken seriously and are initiated by the church for the benefit of those being sent.

A strategic task with a gospel focus that the local believers cannot do: Establish a clearly articulated task for each missions initiative that focuses on bringing the gospel where it would not otherwise be heard. This does not limit the task to mere proclamation, as if the gospel was only a message to be heard. There are many important ways the gospel can be communicated. However, the priority of gospel communication through both word and deed needs to be explicit. If the task chosen is truly part of God’s mission as understood biblically, the gospel will be at the heart of the ministry.

A concern for people groups: Identify a people group that would not otherwise be impacted if a particular ministry was not initiated by the sending church. This restriction helps ensure that the task is strategic and necessary. As noted above, there are two sections of the Acts 1:8 portfolio that are the responsibility of the missions team: (1) establishing and broadening the impact of the gospel where the church has already been established, and (2) bringing the gospel to the unreached. The latter is obviously a missions focus and fits well within the biblical basis of missions as outlined above. However, working with a reached people group can be much more delicate. The danger is that we would take on responsibility that belongs to the local believers in that setting and thus, inadvertently, undermine the growth of the church. A helpful rule of thumb is to ensure that all work is done in partnership with a local congregation and to remember that partnerships are not one-way. That is, helping a church among a reached people group so that the church itself can grow is NOT a partnership. It may be a valid ministry, but it is not a partnership. The beneficiary of any missions partnership should be a third group that is not a member of the partnership team. Partnering within a reached people group should not be for the benefit of either partner, but rather enable them to work synergistically for the benefit of an identified group outside of the partnership.10

A Significant Purpose

In the summer of 2010, the FIFA World Cup was held in South Africa. With incredible fanfare, expense and determination, 32 teams were vying for the glory of their country. For them, and for fans worldwide, this was a significant purpose. God is on mission in this world for a different purpose that is as grand and far reaching as eternity. With far less fanfare, fewer funds, but no less determination, God’s church is invited to join his mission. The transition outlined above is one way to help churches comprehend that mission and align themselves to God’s great purpose. By identifying significant activities through the use of the navigational tool, church missions teams will:

In the summer of 2010, the FIFA World Cup was held in South Africa. With incredible fanfare, expense and determination, 32 teams were vying for the glory of their country. For them, and for fans worldwide, this was a significant purpose. God is on mission in this world for a different purpose that is as grand and far reaching as eternity. With far less fanfare, fewer funds, but no less determination, God’s church is invited to join his mission. The transition outlined above is one way to help churches comprehend that mission and align themselves to God’s great purpose. By identifying significant activities through the use of the navigational tool, church missions teams will:

Discover real needs

Existing among identified people groups

That can be met by active involvement

That advances God’s kingdom

And would not occur unless believers from outside those people groups were to intervene.

The following two articles build on this initial vision so that church missions teams can own the task and motivate others.

Mark spends part of his time assisting churches in developing effective and impacting missions committees. If you are interested, please contact him via the Contact Me form. If you would like to leave a comment about this article, please use the “comment” link at the bottom of this article.

____________________

- 1 The phrase “missions team” is used here to refer to the group of people within a church who have been assigned the task of overseeing the church’s missions responsibility.

- 2 Quoted in Bosch, D.J. 1991. Transforming Mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission. Maryknoll: Orbis, 115.

- 3 The examples given here are based on true examples, only the details have been changed.

- 4 Courses such as Perpectives on the World Christian Movement can provide a biblical and historical basis for the strategic focus on people groups.

- 5 A powerpoint called Understanding Missions that provides the graphics used in the coaching presentations is available for download.

- 6 For further description of the eras of modern missions, see Winters, Ralph. 1981. Four Men, Three Eras, Two Transitions: Modern Missions in Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: 253-261. Note especially the chart on p. 259. For a more detailed theological basis for the concept of “sending” as a basis for missions, see Miley, G. Loving the Church…Blessing the Nations, Waynesboro: Gabriel Pub. 2003. Also see the Cross-Cultural Impact article, Balancing your Missional portfolio.

- 7 The concept of the “portfolio” along with the concentric rings diagrams are further discussed and developed in the Cross-Cultural Impact article, Balancing your Missional portfolio.

- 8 The importance of the Hebrew “goiim” and the Greek “ethne” for missions theology have been discussed often. For example, see John Piper’s discussion of “ethne” in Let the Nations be Glad, 1993. pp. 93-130.

- 9 My role in coaching missions is to stimulate discussion among the participants leading to unity in a direction of their choosing and conviction. Therefore, the presentation of a biblical basis for missions as an unchanging reference point, along with the suggested navigational tool, should lead to discussion and evaluation. Rather than assuming that the participants will accept the navigational tool as authoritative, the coach helps them challenge and think through the concepts until the participants come to “own” them. Suggested questions to create discussion are: “Can the four parts of the navigational tool be rephrased so that they communicate better?”, “What changes would occur in your church’s missions program if this navigational tool was acted upon?”, or “What would it take to initiate this?”

- 10 This deliberately narrow definition of partnership is provided as a important guideline that helps prevent wealthy churches, inexperienced with the complexity of cultural dynamics, from providing aid in a way that can hamper, rather than strengthen, the growth of a cross-cultural sister church.