Theologizing is the personal rational exploration, development, and reflection of theological understanding. It is “faith seeking understanding” (Anslem of Canterbury).

- We all do this because we are constantly making sense of our world.

- We all do this differently because we start in different contexts with a variety of experiences. There are many paths to choose from and questions to prioritize; a multitude of voices clamor for our attention and there are innumerable distractions. Moreover, we are limited in time, ability and interest.

- Some do this better than others. Teachers of theology have spent considerable time exploring different areas of Christian doctrine and can provide important information like a tour guide in the holy land. Without a guide, all we see isa pile of bricks and dirt, but with a guide we are able to connect history with the Bible.

- It is possible to get lost. Inadequate or inappropriate theology is a real danger. The danger cannot be avoided by ignoring theological development; that will only ensure a weak or misguided theological position. Instead, diligence and ongoing interaction with God’s word, other believers, and trusted teachers can keep us growing in our understanding of how God’s revelation of his will and nature can be expressed appropriately within our cultural context.

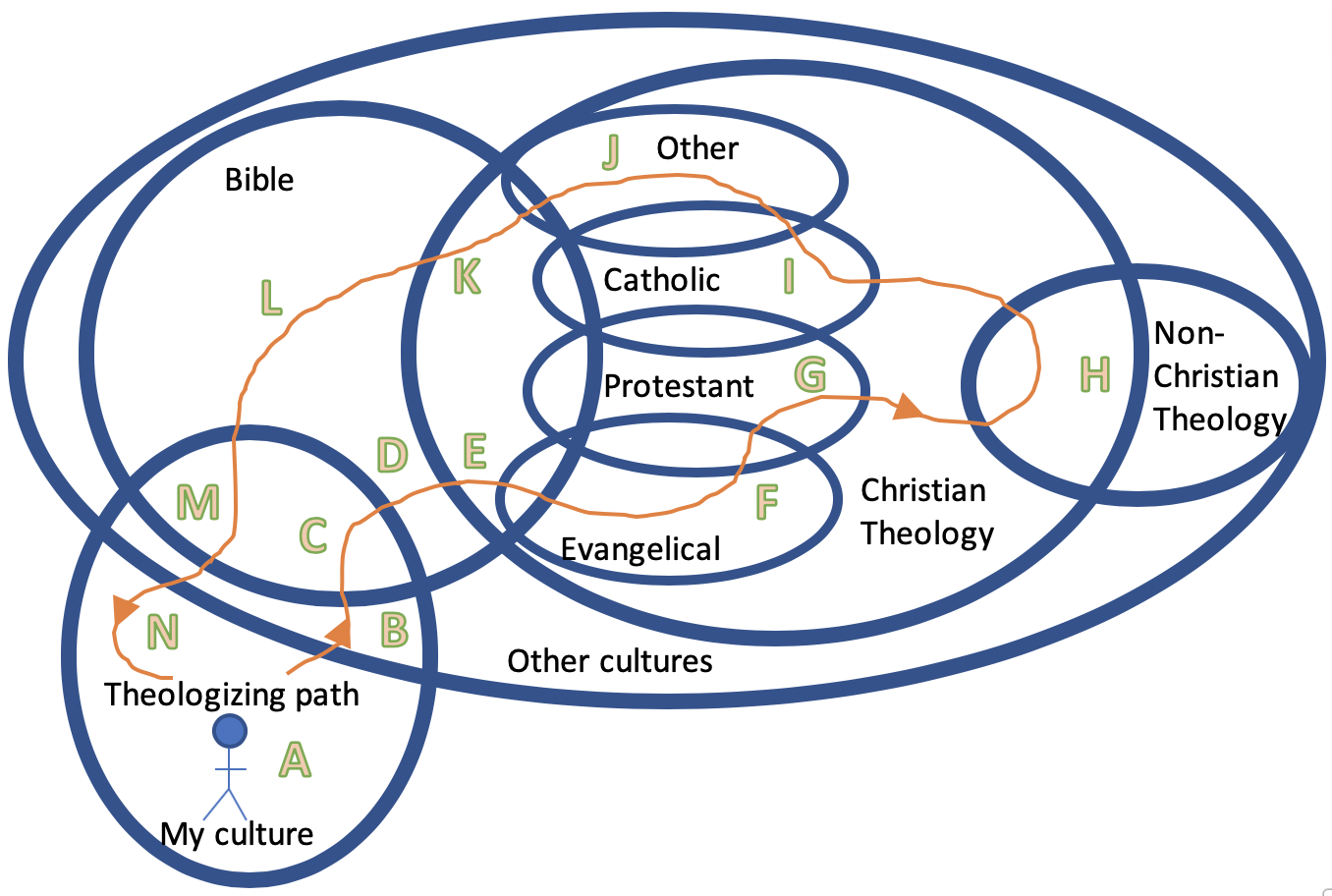

The following “theologizing map” of interlocking circles is a visual aid to understand some key interactions that influence people in the development of their theological perspective.

Explanation of circles:

- Culture is “a way of life – everything that people say, do, have, make, and think – that is learned and shared of a particular society” (Vanhoozer, Everyday Theology, 2007). All of us live and perceive reality through cultural lenses; culture is the “language” through which we perceive, engage, and communicate reality.

- My culture is, of course, just one of many cultural settings. The point is that all people begin their theologizing from within a particular orientation and evaluate all other cultures and teaching from that perspective.

- Bible is located within the culture circle because it is a contextually shaped accommodation for the sake of communication. It is 100% human language and culture and 100% God’s word since it is the channel through which God has revealed his will and nature.

- The four small circles (F, G, I, J) within Christian theology represent foundational doctrines that are formative for particular Christian traditions and they intersect with each other to some extent.

- Doctrine is the “making sense” of faith. That is, it is the rational articulation of faith that categorizes and justifies, from a biblical basis, the questions and challenges of a cultural context. It is characterized by group support, historical longevity, and traditional affirmation, and provides the necessary foundational beliefs that define group identity.

- Christian theology is the study of God rooted in God’s self-revelation found in theBible. This can be formal or informal, profound or simple, written or unarticulated, reasoned or assumed.

- Non-Christian theology is all development of theology not based on biblical sources, including general revelation and the beliefs of non-Christian religious systems.

Explanation of the points on the map:

- Theologizing path is a visual representation of key interactions that are possible in the development of a personal theology.

- The image of the person indicates that as we enter into a theologizing process, we do so located in our cultural context. All that we are taught is perspectival and the questions raised and challenges faced are contextual in origin.

- A –initial theologizing consists of our enculturation in a social context. Like language, ideas about reality are absorbed, worldviews are learned and then assumed, feelings of identity or foreignness are adopted, questions and concerns are all acquired from others. The meanings of theological beliefs, such as heaven, hell, God, angels, demons, soul, and spirit, are assigned from cultural idioms, images and concepts.

- B –indicates the way our initial theologizing is reshaped when we realize that our way of understanding is not absolute.

- C –reflects the beginning of the development of true Christian theology as we engage God’s word.

- D – occurs when there is a realization that the Bible has been influenced by cultural influences other than our own and we begin to explore how those contextual realities have shaped the message.

- E –is the interaction with others who are also engaged in Christian theological development.

- F,G,I,J –are the doctrinal stances of different Christian traditions that can be explored through the writings of those who represent those beliefs.

- H –is the interaction and influence that comes from non-Christian sources or nature (general revelation). Questions, challenges and insights from these sources influence the way we see the world and thus how we describe and understand our theology.

- K –is parallel to E, except that the interaction with other theologizers includes an exploration of their orientation to Christian traditions.

- L –is parallel to D but with the added ability to evaluate how the Christian traditions have interpreted God’s word in light of our own exegetical study ofGod’s word.

- M –is parallel to C but more robust since we have explored and evaluated the theology of others.

- N –represents the need to express our theology verbally and through action in the context of life. Theology that does not shape faith and behavior is a futile exercise. Living out our theology provides further motivation to continue our theologizing as we are faced with more questions and deeper challenges.