Overcoming Obstacles in Disciple Making Movements (DMM)

In their book, TerraNova: A Phenomenological Study of Kingdom Movement Work among Asylum Seekers in the Global North – which provides an overview of DMM critiques in chapter 3, Cocanower and Mordomo divide these critiques into theological, ecclesiological and methodological issues (p. 55). The following focuses on 4 critiques that are pertinent for what Fellowship International is seeking to implement through its DMM efforts.

1. Is it valid to prioritize a discovery process in disciple making over teaching and preaching? (Ecclesiastical).

Is a discovery process such as DBS sufficient for disciple making, or should it be supplemented by more directive and instructional teaching? Does an emphasis on discovery learning as superior for disciple making devalue traditional means of transferring information from the knower to the learner? Is a discovery process appropriate from a biblical and theological perspective? Do discovery Bible studies result in the increase of heretical ideas?

An explanation of the concern:

God uses those with experience and training to help others see new things, things they may be blind to and understanding about what God wants in their lives. Being the church as a community means that we rely on our different perspectives to help each other grow as disciples. Is it possible to become too extreme in embracing a discovery process that we do not engage when we should? Trusting the Holy Spirit to guide is not just an individual issue, but an issue of God speaking through community and through those who are well versed in the Scriptures (cf the apostles seeing their role in community as proclaiming the word) – Phil Webb (private correspondence).

CPM churches have no identifiable leadership gifts in accordance with Ephesians 4, no emphasis on the central role of teaching or proclamation of the Word, and a de-emphasis on the role of the shepherd. – John Massey (quoted in TerraNova, p. 75).

In seeking to avoid one extreme – i.e., passivity – the T4T paradigm has gone to the other – i.e., antipathy towards knowledge or expertise…. Here the dichotomy is between either absolute dependence on the Spirit as Teacher on the one side, or on the other side an excessive dependence on human teachers…. This excluded middle is T4T’s most puzzling and serious failure. – George Terry (quoted in TerraNova, p. 75-76).

My response:

There is a tension between the responsibility of each believer to engage and be obedient to God’s Word trusting the Holy Spirit alone to guide them in faith and obedience and the role of mature leaders to speak prophetically or pastorally into the lives of individuals. The struggle of all DMM practitioners will be to establish a “both-and” approach that ensures (1) a discovery process in which people grow in confidence that they can understand and obey because of their personal relationship with God through Jesus and (2) a communal setting in which mature leaders shepherd believers and speak into their lives. At least part of the answer lies in avoiding the extremes of JUST discovery without the input of competent teachers and JUST following a human teacher as a substitute for discovery and personal obedience.

The discovery process may be a necessary pendulum swing away from an unhealthy dependence on human teachers that sidelines the work of the Spirit, the clarity (perspicuity) of Scripture and the personal responsibility of obedience.

One argument for prioritizing the discovery process is that establishing disciple making through a discovery process leaves open the possibility for teachers to supplement that learning process, while early dependence on a teacher can undermine the responsibility of disciples to learn dependence on the Holy Spirit as they engage God’s Word directly.

2. Are DMMs biblically valid and worth investing in, or are they a recent “fad” that will soon be replaced? (Theological).

Are we so certain that DMMs are a valid, biblically-based mission strategy that we should abandon traditional approaches? If CPMs and DMMs are a renewal or revival of New Testament practices does this undermine the value of the way missions has been practiced to this point? Or has DMM strayed from an appropriate biblical approach?

An explanation of the concern:

CPM is new — and it is new in the overall history of missions. But in the world of modern missionary methods, CPM (circa 2001) is old. It is already being shelved for something newer. Another missionary friend says, “DMM (Disciple-Making Movement) is a kind of next-generation CPM with a focus on obedience-based discipleship and discovery Bible studies, and with less focus on planting churches.” But this new method only serves the point: Missionary fads come and go. Clear proclamation of gospel truth in the context of healthy biblical churches will last until Jesus returns. – Mark Stiles (What could be wrong with Church Planting).

Are the proponents of DMM correct? Is their model as biblical as they claim? Have they restored the proper biblical understanding of missions methodology that has been lost for nearly 1600 years? We will examine these claims of DMM as we shine the light of biblical revelation on each aspect of DMM methodology. We will see that DMM is not the biblical methodology it claims to be. Quite the opposite is true. Major components of DMM are built upon a faulty understanding of the gospel, conversion, discipleship, and the church. – Chad Vegas (A Brief Guide to DMM)

My Response:

The history of the church has been a series of reformations as committed followers of Christ have revisited the teaching of the Bible and then moved towards practices that more closely align with God’s will and nature. DMM principles and practices are an example of such a re-orientation that brings both challenge and hope to those whose current strategies have not been fruitful. This is not a condemnation of past practices, but a recognition that mission practices require evaluation in the light of Scripture that includes acknowledgement of those practices that God is blessing.

By embracing a DMM orientation the goal is not to blindly adopt new tactics, but to reconsider our own practices in light of what is possible, along with a willingness to do whatever it takes. We recognize DMM fruitful practices as strategies that are biblical and effective and therefore should be adopted by those seeking to initiate movements to Christ, while at the same time promoting contextualization of those strategies. Responsible missions looks to what God is doing in the world and seeks to be challenged and informed by what we find. As practitioners we are called to recognize the pattern of the missio Dei that is evident in DMM fruitful practices and adjust our vision and efforts in that direction.

3. Do DMM principles and practices work in every context, or only in specific places? (Methodological)

Are DMM principles and practices universal, requiring only contextualization in specific contexts? Or are DMM principles and practices only valid under certain conditions, such as communal societies that have a respect for Scripture?

An explanation of the concern:

Though T4T may have the most rigid and aggressive approach to evangelism, all Kingdom Movements have some sort of intentional, fast-paced and reproducible model for “seed-sowing.” George Terry expresses a series of concerns, including the biblical basis for such an approach: “The T4T model undervalues the importance of context in evangelism and proof texts [the parable of the sower in Matthew 13] to support its indiscriminate approach” (TerraNova, p. 67).

George Terry [suggests] that, “The more resistant a context is, the more important the relationship becomes. And in this context, I do believe we need to slow it down a bit and take more time, not necessarily to negate our responsibility to share… we share early, but in the context of relationship” (TerraNova, p. 68).

My research and experience have lead me to believe that Kingdom Movements undervalue incarnational ministry prior to sharing the gospel. This is partly a pragmatic issue ― knowing that each person has a limited amount of time that can be invested in discipleship relationships and wanting to prioritize those individuals who are eager to move forward (TerraNova by Bradley Cocanower, João Mordomo, p. 68).

My Response:

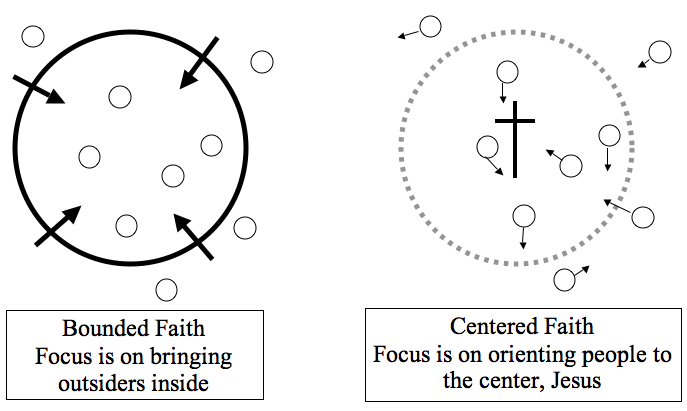

Contextualization is essential. I believe this is a key message of the New Testament from Acts through Revelation as the apostles work out the message of the four Gospels in a first century setting. We have a similar calling to take the contextualized message of the New Testament and contextualize it again for the settings of our ministries. In DMM principles and practices we have an example of modern day contextualizations that God has blessed. Our goal is neither to unconditionally embrace DMM practices that work elsewhere and thoughtlessly practice them, nor to reject the principles as impractical within our contexts without doing the work of contextualizing them.

For example, the principle of “abundant gospel sowing” asks if there is a way to “filter” contacts to discover those with spiritual hunger and openness who become the people we invest in and develop relationships with. Such an approach does not deny the need for building relationships. Rather it suggests that (1) alongside of other relationships we are developing, it is good missions strategy to cast a wide net in order to discover those within whom God is working, and (2) when we find people with a spiritual hunger to know Jesus, those are the ones we invest in.

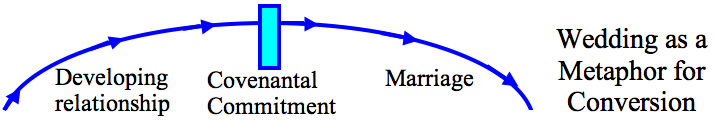

4. Is it appropriate to include seekers in obedience-based disciple making (OBD) before full faith commitment? (Theological)

Does the maxim “What you win them with is what you win them to” apply to disciple making so that seekers are invited to engage God’s Word as if they were believers, or does disciple making only occur after conversion? Is the claim “faith is obedience” biblically appropriate or does it undermine true faith that requires a two-step process: faith followed by obedience?

An explanation of the concern:

Jesus called us to make disciples. But when we place an emphasis on any particular aspect of discipleship, obedience or otherwise, we can stray from the type of holistic and balanced discipleship that Christ calls us to. – Joey Shaw (quoted in TerraNova, p.66).

[Discipleship should be] neither primarily knowledge-based, nor obedience-based, but rather doxologically based, “an intrinsic motivation, a desire and passion based upon love and recognition of the great worth of the Lord Jesus Christ, who desires and deserves to be glorified” – João Mordomo (TerraNova, p. 66).

We simply never see a command, nor a pattern, from our Lord, nor his Apostles, where unbelievers are discipled through regular obedience until they finally have sufficient trust in Christ to be baptized. Rather, the consistent method is the proclamation of the doctrine of the gospel. The proper response is faith and repentance, followed by baptism and teaching toward maturity in Christ. – Chad Vegas (A Brief Guide to DMM).

My Response:

DMM proponents consider obedience to be an essential element of a faith commitment. This contrasts mere faith acknowledgement that does not respond in submission and obedience. When James said, “even the demons believe – and tremble” (Jas 2:19) he was not commending the demons for making the first steps of belief, but condemning them for not having saving faith, which is submission to the will of God.

This commitment to obedience is reflected in the conviction within Fellowship International that “What you win them with is what you win them to.” As people come to saving faith through obedience to God’s Word, that practice and response will continue as the way they live out their faith. Consider the following quote from G. MacDonald:

Do you ask, ‘What is faith in him?’ I answer, The leaving of your way, your objects, your self, and the taking of his and him; the leaving of your trust in men, in money, in opinion, in character, in atonement itself, and doing as he tells you. I can find no words strong enough to serve for the weight of this necessity—this obedience. It is the one terrible heresy of the church, that it has always been presenting something else than obedience as faith in Christ.

…

Instead of asking yourself whether you believe or not, ask yourself whether you have this day done one thing because he said, Do it, or once abstained because he said, Do not do it. It is simply absurd to say you believe, or even want to believe in him, if you do not do anything he tells you (Unspoken Sermons: The Truth in Jesus).

This unwillingness – even embarrassment – to talk about spiritual issues is common in Canada, but it is a cultural, not a universal phenomenon. In Pakistan, where we served among the Sindhi people for a number of years, conversations about religion are common and natural. I would bring Sindhi booklets with me while traveling on the bus. As I sat and read them, curious onlookers would ask me about the booklets and I would respond by explaining that they were about Jesus and the Bible. Inevitably, people would ask for copies and some of them would come to visit me so that we could talk more about spiritual things.

This unwillingness – even embarrassment – to talk about spiritual issues is common in Canada, but it is a cultural, not a universal phenomenon. In Pakistan, where we served among the Sindhi people for a number of years, conversations about religion are common and natural. I would bring Sindhi booklets with me while traveling on the bus. As I sat and read them, curious onlookers would ask me about the booklets and I would respond by explaining that they were about Jesus and the Bible. Inevitably, people would ask for copies and some of them would come to visit me so that we could talk more about spiritual things. But is this approach legitimate, or are we selling out to cultural pressures? By choosing the route of Significant Conversations because it is more comfortable and natural for us in our pluralist society, does this mean we are neglecting our call to proclaim the gospel? Are we in danger of “watering down the gospel” by presenting it as only one of many beliefs? Apart from the important clarification that this approach does not claim to replace proclamation, there are a number of reasons why dialogue represents an appropriate contextualization of evangelism that fits with our cultural “language” and mood, rather than an inappropriate capitulation to societal pressures.

But is this approach legitimate, or are we selling out to cultural pressures? By choosing the route of Significant Conversations because it is more comfortable and natural for us in our pluralist society, does this mean we are neglecting our call to proclaim the gospel? Are we in danger of “watering down the gospel” by presenting it as only one of many beliefs? Apart from the important clarification that this approach does not claim to replace proclamation, there are a number of reasons why dialogue represents an appropriate contextualization of evangelism that fits with our cultural “language” and mood, rather than an inappropriate capitulation to societal pressures. Dialogue is a

Dialogue is a  In our Canadian context, the task of determining the true faith among all the available options through the use of logic is impossible. If the gospel is proclaimed in an objective propositional manner, the implication is that it can be verified against a normative standard through a rational and logical process. The response in our Canadian context is to challenge absolute declarations and to question normative standards. When this happens, the task shifts from proclamation to an attempt to verify absolute claims and to defend norms. This very quickly becomes unwieldy. Not only is the information that needs to be evaluated too vast to process (think of trying to sort out the internet!), but the assumptions that determine which facts should take priority cannot be proven by a logical process. Unless both parties are committed to a long academic and potentially tedious process of collecting the facts and challenging assumptions, the discussion is usually unhelpful, resulting in stalemate and frustration. Because the presenter of the gospel is required to be an expert in providing objective proofs in this model, it is one reason why many Christians shy away from sharing their faith.

In our Canadian context, the task of determining the true faith among all the available options through the use of logic is impossible. If the gospel is proclaimed in an objective propositional manner, the implication is that it can be verified against a normative standard through a rational and logical process. The response in our Canadian context is to challenge absolute declarations and to question normative standards. When this happens, the task shifts from proclamation to an attempt to verify absolute claims and to defend norms. This very quickly becomes unwieldy. Not only is the information that needs to be evaluated too vast to process (think of trying to sort out the internet!), but the assumptions that determine which facts should take priority cannot be proven by a logical process. Unless both parties are committed to a long academic and potentially tedious process of collecting the facts and challenging assumptions, the discussion is usually unhelpful, resulting in stalemate and frustration. Because the presenter of the gospel is required to be an expert in providing objective proofs in this model, it is one reason why many Christians shy away from sharing their faith. We need to ask ourselves “what do we really want?” If we want to win and be proved right and others proved wrong, then a powerful proclamation may be called for. However, if the goal is to see people come to Christ, then it should be recognized that in our cultural setting the way of dialogue will often result in a greater willingness to explore the gospel message. At the very least, it provides a means by which the discussion of spiritual issues can be brought into the public forum in a way that frees Christians to express their beliefs without needing a philosophical or theological education to prove the truth of the gospel.

We need to ask ourselves “what do we really want?” If we want to win and be proved right and others proved wrong, then a powerful proclamation may be called for. However, if the goal is to see people come to Christ, then it should be recognized that in our cultural setting the way of dialogue will often result in a greater willingness to explore the gospel message. At the very least, it provides a means by which the discussion of spiritual issues can be brought into the public forum in a way that frees Christians to express their beliefs without needing a philosophical or theological education to prove the truth of the gospel. Evangelism is traditionally thought of as proclamation. Because we have a message, the message, that the world needs to hear, we are encouraged to tell the world the story of Jesus. This approach has a strong history, from Paul’s declaration on Mars hill (Acts 17) through to Billy Graham’s gospel meetings. Most evangelical churches consider preaching from the pulpit an important aspect of spreading the message. There are also many programs that encourage Christians to memorize key verses, produce creative diagrams and use provocative questions to communicate the gospel message. This article does not intend to undermine the value of these methods when used in the right context, nor suggest that we should not communicate the message of Jesus to others. I have spent many productive years in ministry focusing on proclamation and appreciate this activity. However, my experience tells me that, in our Canadian context, expressions of superior knowledge, certainty and exclusivity usually result in opposition and rejection. People are hardened against exclusive proclamations of the gospel message, and to avoid uncomfortable and potentially disastrous confrontations, many Christians leave attempts to talk about the gospel to those who have a “gift” of evangelism.

Evangelism is traditionally thought of as proclamation. Because we have a message, the message, that the world needs to hear, we are encouraged to tell the world the story of Jesus. This approach has a strong history, from Paul’s declaration on Mars hill (Acts 17) through to Billy Graham’s gospel meetings. Most evangelical churches consider preaching from the pulpit an important aspect of spreading the message. There are also many programs that encourage Christians to memorize key verses, produce creative diagrams and use provocative questions to communicate the gospel message. This article does not intend to undermine the value of these methods when used in the right context, nor suggest that we should not communicate the message of Jesus to others. I have spent many productive years in ministry focusing on proclamation and appreciate this activity. However, my experience tells me that, in our Canadian context, expressions of superior knowledge, certainty and exclusivity usually result in opposition and rejection. People are hardened against exclusive proclamations of the gospel message, and to avoid uncomfortable and potentially disastrous confrontations, many Christians leave attempts to talk about the gospel to those who have a “gift” of evangelism. One young woman related the following incident to my wife, Karen. She was working at Starbucks and commented to a customer who was heading to a Halloween program with her young children, “I don’t believe in Halloween.” The response was immediate, aggressive and abrupt, “Well, I do!” There was an uncomfortable pause until the drink was finally ready and handed over. Such interactions are far from uncommon. Unfortunately, rather than working out an alternative style that could lead to more productive conversations, such approaches are often justified with comments such as, “Well, maybe it will cause her to think about it.”

One young woman related the following incident to my wife, Karen. She was working at Starbucks and commented to a customer who was heading to a Halloween program with her young children, “I don’t believe in Halloween.” The response was immediate, aggressive and abrupt, “Well, I do!” There was an uncomfortable pause until the drink was finally ready and handed over. Such interactions are far from uncommon. Unfortunately, rather than working out an alternative style that could lead to more productive conversations, such approaches are often justified with comments such as, “Well, maybe it will cause her to think about it.” As noted in the article

As noted in the article  This past week I had a discussion with a couple of fellow believers who had had a significant conversation with an elderly person who was in the last days of his life. They were talking to him of the grace and forgiveness offered by God. His response was, “I have cheated and lied. I have not treated people properly. God will not let me into heaven.” They did not know how to respond.

This past week I had a discussion with a couple of fellow believers who had had a significant conversation with an elderly person who was in the last days of his life. They were talking to him of the grace and forgiveness offered by God. His response was, “I have cheated and lied. I have not treated people properly. God will not let me into heaven.” They did not know how to respond. The goal is to provide a support network in the church that will enable believers to be intentional Christians in their day-to-day relationships. This process is a form of contextualization in which we learn how to engage the common opinions and beliefs of those around us from the perspective of our own convictions and view on life. Because we are followers of Christ, our perspective on life will be centered on our faith in him.

The goal is to provide a support network in the church that will enable believers to be intentional Christians in their day-to-day relationships. This process is a form of contextualization in which we learn how to engage the common opinions and beliefs of those around us from the perspective of our own convictions and view on life. Because we are followers of Christ, our perspective on life will be centered on our faith in him. So how could the conversation be continued when someone declares, “God will not let me into Heaven”? If this question was brought up for discussion in a significant conversations forum, I would probably add my thoughts to the exchange in the following way.

So how could the conversation be continued when someone declares, “God will not let me into Heaven”? If this question was brought up for discussion in a significant conversations forum, I would probably add my thoughts to the exchange in the following way. Conversations

Conversations

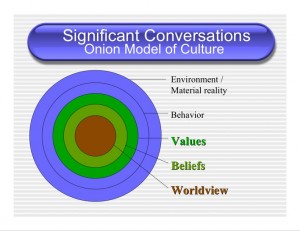

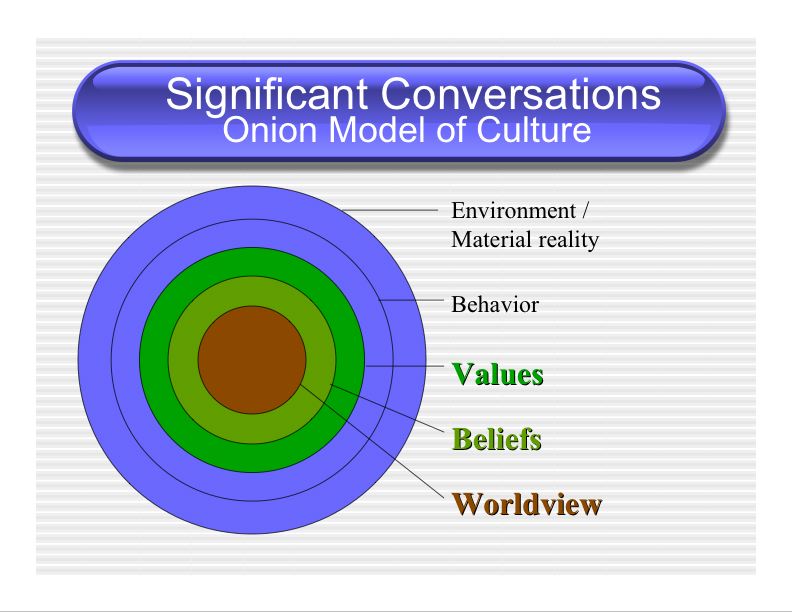

Moving Deeper in the Onion Model of Culture

Moving Deeper in the Onion Model of Culture