A Model for developing a Contextualized presentation of the Gospel

In the previous articles of this series, I argued that there are cultural reasons why one biblical picture of the atonement may resonate1 with a people group, while others will be problematic. I suggested that believers who seek to communicate the significance of the cross of Christ across cultural barriers will need to be aware of the cultural values and perspectives of the people they are addressing in order to discover appropriate metaphors that reveal the gospel message in a way that speaks to their felt needs. In this article, I use Roland Muller’s three cultural dichotomies as a model towards analyzing cultures for the purpose of discovering an explanation of the atonement that will connect with the hearers.

In the previous articles of this series, I argued that there are cultural reasons why one biblical picture of the atonement may resonate1 with a people group, while others will be problematic. I suggested that believers who seek to communicate the significance of the cross of Christ across cultural barriers will need to be aware of the cultural values and perspectives of the people they are addressing in order to discover appropriate metaphors that reveal the gospel message in a way that speaks to their felt needs. In this article, I use Roland Muller’s three cultural dichotomies as a model towards analyzing cultures for the purpose of discovering an explanation of the atonement that will connect with the hearers.

Understand the Intended Audience

A missionary to Japan, Norman Kraus,2 realized that the forensic metaphor of the atonement, familiar to North American evangelicals – that Jesus died to pay the penalty for our sins – did not make sense to the majority of Japanese. In exploring the assumptions behind this rejection of the atonement, he discovered that they were interpreting the presentation according to a very different understanding of justice. The Western concept of justice requires an impartial decision based on immutable laws leading to a debt that must be paid. For the Japanese the issue is not guilt banished through punishment, but shame that must be overcome through the establishment of right relationships and the restoration of honor.

A missionary to Japan, Norman Kraus,2 realized that the forensic metaphor of the atonement, familiar to North American evangelicals – that Jesus died to pay the penalty for our sins – did not make sense to the majority of Japanese. In exploring the assumptions behind this rejection of the atonement, he discovered that they were interpreting the presentation according to a very different understanding of justice. The Western concept of justice requires an impartial decision based on immutable laws leading to a debt that must be paid. For the Japanese the issue is not guilt banished through punishment, but shame that must be overcome through the establishment of right relationships and the restoration of honor.

Evangelical scholars excel at exegeting3 the Scriptures. At the heart of our faith is a commitment to God’s word, and much work has been done to understand the meaning of God’s word within the setting of the author and original audience, as well as to determine the relevance and impact of that revelation for a 21st century audience. The cross-cultural worker, however, has to move one step further, and discover ways to communicate that message in a relevant and impacting manner to hearers with different values, perspectives and worldview. They must not just exegete the Scriptures, but also the cultural context in which the audience lives. The way the gospel impacts and is significant to cross-cultural communicators may be very different from their hearers because of the cultural grid through which they organize and perceive the world and reality.

It takes time, relationships and intentional exploration to discover and comprehend the cultural complexities of a people group. There are a number of resources available to cross-cultural communicators that aid in the development of a “Cultural Quotient,” and promote the development of the skills needed to understand a different people group.4

Identify the Cultural Orientation towards Spiritual Brokenness

If Kraus is correct in his assessment, the implications for the presentation of the gospel are critical. The communicator of the gospel must either explain the Western paradigm for justice within which the forensic metaphor can be understood, or discover a different metaphor for the cross, one that would resonate with the Japanese view of reality. The former approach is not viable for a number of reasons.5 First, it requires the hearers to adjust their assumptions and accept foreign values. This limits the attractiveness of the gospel message to those who are willing to move away from their culture to some extent. Second, the message remains unattractive to the majority of community members who only value those things that fit within their way of perceiving reality. Third, time and energy are required for a hearer to understand and assess the value of the message for their lives. Unless the person has a strong dissatisfaction with their current spiritual condition, has the patience to spend the time it takes to puzzle through the presentation, and has a significant relationship with the messenger, they are unlikely to make the investment required to decipher a message that, at first hearing, seems irrelevant to their context. Fourth, even if the hearers can grasp the presentation intellectually, it still does not touch their felt need. Understanding is insufficient, there must also be perceived significance.

Roland Muller proposes three dichotomies6 at work in cultures that reveal people’s sensitivity to brokenness and dysfunction in their lives. These three dichotomies provide a helpful framework7 that can be used discover the primary spiritual felt need of a specific people group. He suggests that all cultures exhibit each of these dichotomies to some extent, but usually one will be the predominant, default way of judging, processing and alleviating dysfunction.

Roland Muller proposes three dichotomies6 at work in cultures that reveal people’s sensitivity to brokenness and dysfunction in their lives. These three dichotomies provide a helpful framework7 that can be used discover the primary spiritual felt need of a specific people group. He suggests that all cultures exhibit each of these dichotomies to some extent, but usually one will be the predominant, default way of judging, processing and alleviating dysfunction.

Guilt – Innocence

The rule of law is a high value in Canadian society. It is not unheard of, in fact, it is expected, that a father turn his son into the authorities if the son commits a crime. This elevation of law to absolute status, beyond even family loyalty, is a feature of Western societies. There are many reasons for this orientation, not least of which is the preeminence of individual values over community concerns or family ties. To maintain a reasonable level of control, boundaries are set by governments within which an individual has the freedom to function. These boundaries are continually being renegotiated, but the point here is the establishment of an external standard to which we are obliged to conform. Because this is such a high value, a dysfunctional action is primarily understood as acting against a law, which is understood as guilt whether or not transgressors feel guilty.

A prominent politician in BC was caught drinking and driving in another country. It was a scandal when reported in BC, but part of the politician’s defense was that the laws of that country were more lax than in BC, and therefore he should be judged according to those standards and not as harsh as if he had been caught in BC. For him, guilt was based on a standard of law, rather than on a deeper moral foundation or a sense of identity with a particular community to guide his actions.

A prominent politician in BC was caught drinking and driving in another country. It was a scandal when reported in BC, but part of the politician’s defense was that the laws of that country were more lax than in BC, and therefore he should be judged according to those standards and not as harsh as if he had been caught in BC. For him, guilt was based on a standard of law, rather than on a deeper moral foundation or a sense of identity with a particular community to guide his actions.

“Imagine a classroom full of grade school kids. Suddenly, the intercom interrupts their class. Johnny is being called to the principle’s office. What is the immediate reaction of the other children? “What did you do wrong?” they ask. Even our children immediately assume guilt. Perhaps the school principal is going to hand out rewards, but our society conditions us to expect the worst, and we feel pangs of guilt” (:24).

In a context where brokenness and dysfunctionality are defined in terms of “guilt,” restoration to a state of innocence is the highest value, a condition that often cannot be met.

Shame – Honor

Many cultures (e.g., Japan, Pakistan and other Asian and middle Eastern countries) function on the basis of shame and honor. People assess their value by the way they are perceived by others. Their interpersonal relationships provide the motivation for their actions. The issue of brokenness is not guilt – whether or not they have transgressed a law – but shame – how a particular action is perceived by themselves and others within the context of a community that determines their identity.

“Why did you leave?”

When Berean8 became a follower of Christ he was kicked out of his extended family and forced to live apart from his wife and three girls for a period of two years. At that time, his younger brother came to him and said, “Why did you leave? Mother has been weeping and weeping for you. Come home.” Upon his return, his father commanded, “Don’t say a word. I don’t want to hear about your faith.” He then went to the neighbors and told them that his son had turned from his Christian faith and become a Muslim again. The concern was the family honor in the eyes of the community, not adherence to a law or concern about facts.

Muller provides his own experience of living within a shame-honor culture but functioning according to a personal guilt-innocence paradigm:

“I would try to act correctly and they would try to act honorably, not shamefully. I was busy trying to learn the rights and wrongs of their culture and explain them to new people arriving from the west. But somehow my framework of right versus wrong didn’t fit what was actually happening. The secret wasn’t to act rightly or wrongly in their culture. It wasn’t that there was a right way and a wrong way of doing things. The underlying principle was that there was an honorable and dishonorable way of doing things” (:47).

Failing the expectations of those who speak for their community is the ultimate catastrophe. Restoration to acceptance and a position of honor is the need, a requirement that may be impossible.

Fear – Power

Other cultures, notably animistic cultures and many African contexts, see the world primarily as a power struggle. The spirit world is very real and much effort is spent either appeasing powers that may harm, or appealing to powers that may address the individual’s needs by giving control over harmful spirits. Transgression in this context is defined as an offence to the existing powers, the results of which are evident in disasters and personal set-backs, rather than through a set of laws.

Other cultures, notably animistic cultures and many African contexts, see the world primarily as a power struggle. The spirit world is very real and much effort is spent either appeasing powers that may harm, or appealing to powers that may address the individual’s needs by giving control over harmful spirits. Transgression in this context is defined as an offence to the existing powers, the results of which are evident in disasters and personal set-backs, rather than through a set of laws.

This perspective is evident among Sindhis as well, who often look to saints and holy men to provide amulets with Quranic verses or prescribe rituals so that difficulties in their lives can be overcome. Muller clarifies:

“In order to deal with these powers, rituals are established which people believe will affect the powers around them. Rituals are performed on certain calendar dates, and at certain times in someone’s life (rites of passage), or in a time of crisis.

In order to appease the powers of the universe, systems of appeasement are worked out. They vary from place to place. Some civilizations offer incense while some offer their children as sacrifices to gods. However it is done, a system of appeasement, based on fear is the norm for their worldview” (:44).

In a fear – power system, the transgression is often unidentified. That “sin” (offense to a spirit power) has occurred is evident from the difficulty or catastrophe that has occurred. Restoration to success or healing requires an outside power to counteract the action of the spirits who have caused the difficulty. The suffering person may need to try many different rituals before the correct appeasement is discovered.

Back to Eden

Roland Muller provides a biblical basis for these cultural dichotomies from the story of the fall in Genesis which he calls “the Eden effect” (:15). When Adam and Eve disobeyed God – the essence of sin from a biblical perspective – three things occurred. First, they realized they were naked (Gen 3:7), the experience of shame. Second, they hid themselves from God (Gen 3:8), the experience of fear. Third, their disobedience was exposed (Gen 3:17), the experience of guilt. These three aspects of the fall or brokenness of humanity are evident in every culture, and have one original cause: rebellion against God.

Roland Muller provides a biblical basis for these cultural dichotomies from the story of the fall in Genesis which he calls “the Eden effect” (:15). When Adam and Eve disobeyed God – the essence of sin from a biblical perspective – three things occurred. First, they realized they were naked (Gen 3:7), the experience of shame. Second, they hid themselves from God (Gen 3:8), the experience of fear. Third, their disobedience was exposed (Gen 3:17), the experience of guilt. These three aspects of the fall or brokenness of humanity are evident in every culture, and have one original cause: rebellion against God.

Each culture strives for wholeness in each of these areas, with one aspect being the primary concern. To some extent, cultures succeed in mitigating some of the impact of the fall, but the effects are still suffered by all. When Jesus came as the savior of the world, he addressed the heart of the matter: sin. Rather than a focus on past wrong deeds we have done, sin describes a rebellion or turning away from God’s desire for us, a rejection of the one who is the source of life and light and goodness. Therefore, Jesus begins his ministry with a call to repentance (Mk 1:15). He turned people from their rebellion and provided a way back into a right relationship with God through the cross. How that rebellion and restoration is expressed will depend on the emphasis within each people group, whether guilt, shame or fear.

Discover what Resonates

the cross demonstrates God’s love by Jesus voluntarily identifying himself with our sin, and therefore our shame

Kraus searched for an atonement metaphor that would resonate with the Japanese view of reality. This commitment is a necessity for the cross-cultural worker who believes that the gospel can be communicated through all languages and known within all cultures. The goal is to discover a metaphor that resonates with the values and perspectives of the hearers. The picture adopted by Kraus was that the cross demonstrates God’s love by Jesus voluntarily identifying himself with our sin, and therefore our shame. The establishment of a relationship with us while we are in a state of shame restores our honor. We repent of that which causes shame and rely on God’s values for our meaning in life. This brief description does not do justice to Kraus’ development of the meaning of the cross in a Japanese context and should not be critiqued solely on the basis of my representation. For the person who desires to communicate the gospel cross-culturally, his reflections are worth studying because they reveal a contextualizing process that is helpful in other contexts as well. The result is a metaphor that is “easily understood” in the Japanese setting and also uses “images that are theologically sound and not so enmeshed in the culture that they fail to challenge the culture with the scandal of the cross.”9

Each dichotomy provides a framework within which potential metaphors can be discovered that may resonate with a people group.

Guilt – Innocence

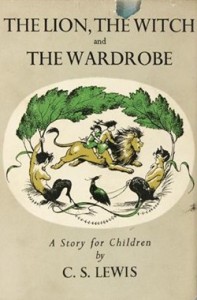

A classic metaphor for this dichotomy is provided by CS Lewis in the first book of the Chronicles of Narnia, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Edmund has repented of his treachery and been rescued from the Witch, but sin is not so easily removed. There is something that Aslan (the lion who is a picture of Jesus) needed to do:

‘You have a traitor there, Aslan,’ said the Witch. Of course everyone present knew that she meant Edmund. But Edmund had got past thinking about himself after all he’d been through and after the talk he’d had that morning. He just went on looking at Aslan. It didn’t seem to matter what the Witch said.

‘You have a traitor there, Aslan,’ said the Witch. Of course everyone present knew that she meant Edmund. But Edmund had got past thinking about himself after all he’d been through and after the talk he’d had that morning. He just went on looking at Aslan. It didn’t seem to matter what the Witch said.

‘Well,’ said Aslan. ‘His offence was not against you.’

‘Have you forgotten the Deep Magic?’ asked the Witch.

‘Let us say I have forgotten it,’ answered Aslan gravely. ‘Tell us of this Deep Magic.’

‘Tell you?’ said the Witch, her voice growing suddenly shriller. ‘Tell you what is written on that very Table of Stone which stands beside us? Tell you what is written in letters deep as a spear is long on the fire-stones of the Secret Hill? Tell you what is engraved on the scepter of the Emperor-Over-Sea? You at least know the Magic which the Emperor put into Narnia at the very beginning. You know that every traitor belongs to me as my lawful prey and that for every treachery I have a right to a kill.’

…

‘And so,’ continued the Witch, ‘that human creature is mine. His life is forfeit to me. His blood is my property.’

…

At last they heard Aslan’s voice, ‘You can all come back,’ he said. ‘I have settled the matter. She has renounced the claim on your brother’s blood.’10

Aslan “settled the matter” by giving his life to pay the penalty demanded by the “Emporer’s Magic” so that Edmund could be set free.

Shame – Honor

A Japanese woman who came to Christ as an adult was explaining her conversion experience to my wife, Karen. When she spent time with her friends, she would come away feeling dissatisfied and she concluded that her friends, although average Japanese girls, talked and acted improperly. Then, one day, the realization dawned that she was no different, and she began to be sensitive to her “dirty heart.” She did not know how to deal with her “dirty heart” until she began to explore the message of Jesus, and found cleansing in him. Karen pursued the conversation and asked, “What is the word for ‘sin’ in Japanese, and what does it mean?” The woman replied that it referred to evil deeds like murder and stealing. Karen then pointed out that the word being used for “sin” did not fit with her conversion story. She had not committed “sin” (according to the Japanese word mentioned). Instead, she had grown to be ashamed of the way she had fallen short of an ideal that she longed for. Most Japanese would not feel a need for salvation from “sin,” but it is possible that many, like this woman, would sense the brokenness and shame of a “dirty heart.”

A Japanese woman who came to Christ as an adult was explaining her conversion experience to my wife, Karen. When she spent time with her friends, she would come away feeling dissatisfied and she concluded that her friends, although average Japanese girls, talked and acted improperly. Then, one day, the realization dawned that she was no different, and she began to be sensitive to her “dirty heart.” She did not know how to deal with her “dirty heart” until she began to explore the message of Jesus, and found cleansing in him. Karen pursued the conversation and asked, “What is the word for ‘sin’ in Japanese, and what does it mean?” The woman replied that it referred to evil deeds like murder and stealing. Karen then pointed out that the word being used for “sin” did not fit with her conversion story. She had not committed “sin” (according to the Japanese word mentioned). Instead, she had grown to be ashamed of the way she had fallen short of an ideal that she longed for. Most Japanese would not feel a need for salvation from “sin,” but it is possible that many, like this woman, would sense the brokenness and shame of a “dirty heart.”

Fear – Power

Paul Long provides a powerful true story of the conversion of a chieftain, Kalonda, within a fear – power worldview. Kalonga summoned Long who went to see him with a few other Congolese Christian leaders. After proper greetings, Long asked Kalonda what the meeting was about:

Kalonda’s reply startled me. “Tell me about the white man’s God.”

When I throw down this medicine … my spirits will withdraw their protection. And I will die

“The God I follow is not a white man’s God. He is the Father of the New Tribe. His people. Jesus Christ is the great Chieftain of the New Tribe. And He accepts anyone who will follow Him. My friends here are also members of the· New Tribe. They will tell you about it.” And I turned to my Congolese colleagues who really understood the battle old Kalonda was facing. One of my companions was an old witch doctor turned Christian and now an effective pastor among his people. I accompanied with deep concern the battle taking place between the powers which are real and the liberation which is possible.

Copper charm bracelets adorned the once-strong spear arm at the old chief. “You still trust in your medicine,” observed Pastor Mutombo. “Why do you ask about another God?”

With great reluctance, the old man slipped the bracelets from his arm, dropped them in the dust, and said, “Now tell me, ‘Teller of the Word’ about your powerful God.”

With those copper bands lying at our feet, I began to realize something of the price he was having to pay for what he asked. He had just renounced his potency.

…

“Now,” the pastor continued, “the war medicine on your belt shows where you look for power.”

After a long, thoughtful pause, the old warrior cut the small skin bag from his belt and dropped it in the dust.

“Now the ‘counter-hex’ packet at your neck.” The old man put a trembling hand to the thong around his neck. This little charm held his protection against all his enemies and made their magic of no power. Silently we waited until, at length, he broke the thong and let his “security” fall at our feet. Grunts of respect for his courage echoed around the ring of watching tribesmen.

…

“This is all the protection I have,” Kalonda said. But the pastor was evidently waiting for another, more costly surrender. “Now get your ‘life charm’ Kalonda, and I will tell you about the God of the New Tribe.”

The old man trembled, broke out in perspiration, shook his head and wrapped his tattered blanket across his bony chest. The three old wives had remonstrated with his renunciation of his medicines, and, with this last demand, they commenced the death wail, and started tossing dust in the air over their heads.

…

“Teller of the Word,” he said, holding out his little packet in his bony hands, “you have asked the life of Kalonda! This medicine has protected my life from all my enemies for many years. Many still live who hate me and have curses on my life. When I throw down this medicine all their curses will fall on me, my spirits will withdraw their protection. And I will die. But Kalonda is not afraid to die.”

As the packet dropped in the dust, the old chieftain straightened to his full height, lifted his old eyes to the distant hills, and waited for death.

…

It took a long time to answer questions from old Kalonda and his people. Questions about the God, he said, he had always feared but never known. As the afternoon shadows lengthened, the old chieftain arose with dignity before his people. In a quiet, confident voice he announced, “Kalonda has a new chieftain. I follow ‘Yesu Kilisto’ and He will help me across the river, lead me through the dark forest, and take me to His village where I can sit with His people. I belong to the New Tribe. Kalonda wants all his people to follow Nfumu Yesu, [Chieftain Jesus], and go with Him to the Village of God.”11

Conclusion

The essence of contextualization is the communication of a truth using the concepts, metaphors and categories of understanding that form the frame of reference and communication of a group of people. The right terminology and images cannot be discovered without serious reflection of their culture and worldview. The cross-cultural communicator of the gospel is required to initiate a “dance” between the text of God’s word and the reality of the context in order to discover those “bridges” that communicate the truth of the cross. Even if the message is not accepted at first, the response should be, “Oh, we need that. I wish it was true!”

Mark spends part of his time assisting churches in developing significant cross-cultural relationships. If you are interested, please contact him via the Contact Me form. If you would like to leave a comment about this article, please use the “comment” link at the bottom of this article.

____________________

- 1 As in the other articles in this series on conversion metaphors, “resonance” refers to the way the hearer perceives and responds to the message. It goes beyond comprehension to describe the impact of the passage upon the values and beliefs of the reader or listener. But it is not limited to positive acceptance by a people group. When the message resonates, this “does not mean that a challenge to or contrast with cultural values is not possible. The concept of resonance refers to any concept which speaks either negatively or positively to the reality within which the person lives. The point is that it speaks relevantly and significantly” (Naylor 2004:7-8).

- 2 In Jesus Christ our Lord: Christology from a Disciple’s perspective (Scottdale, Penn: Herald, 1990), Norman Kraus examines Christology as an exercise of contextualization within a Japanese society. Joel B. Green & Mark D. Baker summarize his work with helpful illustrations in Recovering the Scandal of the Cross: Atonement in New Testament & Contemporary Contexts (Downers Grove: IVP, 2000), 153-170. The latter is the primary source for this illustration.

- 3 To “exegete” is to interpret or explain a text or context so that the meaning intended by the author (or “meaning-makers” of the context) is communicated to others.

- 4 I would be glad to send you a list of my recommended books on developing cross-cultural skills. Please use the form below to contact me.

- 5 The adoption of a shame-based metaphor presentation of the atonement should not be misrepresented as a rejection of the penal substitution picture of the atonement. Even as North American Christians can grow in their appreciation of the cross of Christ by seeing the impact of the cross through the eyes of a shame culture, so believers in Japan who have been delivered from shame can in turn develop a deeper sense of gratitude by recognizing how Jesus’ sacrifice also saves us from guilt.

- 6 The three dichotomies, complete with underlying theory and theology are developed in Roland Muller’s book, Honor-Shame: Unlocking the Door (Xlibris, 2000). The page numbers in the body of the text refer to his book.

- 7 All models have their limitations, and this is no exception. However, it is a helpful tool to begin the complex process of understanding another culture for the purpose of gospel communication.

- 8 Not his real name.

- 9 Green and Baker, 168.

- 10 CS Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1950), 128-130.

- 11 Recounted in Hiebert, P Anthropological Insights for Missionaries. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1985), 199-201.