A Shift in Communicating Salvation

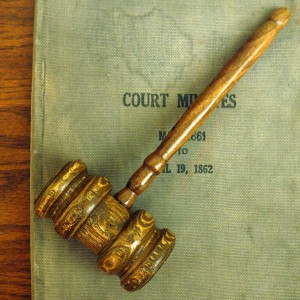

There was a pause in the conversation. My visitor considered seriously the illustration I had presented to him. He then spoke words that became a critical turning point in my ministry in Pakistan – he challenged my understanding of salvation. To present the gospel, I would often use an illustration of a judge in order to communicate the need for Jesus’ death and resurrection. My argument was that if someone commits a crime, a just judge can’t forgive wrongdoing based on past good deeds; he must punish the crime. By implication, God cannot forgive our sins without payment or intervention from someone who can pay the price.

There was a pause in the conversation. My visitor considered seriously the illustration I had presented to him. He then spoke words that became a critical turning point in my ministry in Pakistan – he challenged my understanding of salvation. To present the gospel, I would often use an illustration of a judge in order to communicate the need for Jesus’ death and resurrection. My argument was that if someone commits a crime, a just judge can’t forgive wrongdoing based on past good deeds; he must punish the crime. By implication, God cannot forgive our sins without payment or intervention from someone who can pay the price.

I had presented this scenario to my Muslim visitor. After thinking for a few minutes he said, “It is true that a judge must be just, but a just judge can also be merciful. Mercy need not be in conflict with justice, and God is a merciful God. God can forgive without undermining justice.” I had been long enough in the country to realize the implication of this statement and I was struck silent for a time. I finally replied, “You are right. I will need to think about this.”

This was a crisis point for me and I realized that the judicial view of salvation that I had been teaching, based on Paul’s forensic metaphors in Romans, did not resonate in this Muslim setting. My assumption was that people were depending on their good works for forgiveness, but this was not necessarily the case. Their hope was in the mercy of a God who knows our weakness and is willing to forgo punishment. In Canada, we live in a guilt–innocence culture; sin is doing wrong against a moral code and we have a high regard for the rule of law. On the other hand, Pakistani Muslims live in a shame-honor culture.1 Forgiveness is always possible when a command is broken, but a person who dishonors their family faces disastrous consequences, often without the hope of redemption. I set aside a couple of days to wrestle with this question and discovered a perspective on the salvation of Christ that connects more closely with their felt need for a savior: through bearing the cross of shame (Gal 3:13), Jesus joins us in our separation from God. Because his relation to the Father has not been broken and he is alive with God, we can have a restored relationship with God by becoming “in Christ” (to use Paul’s phrase, eg. Rom 8:1).

This was a crisis point for me and I realized that the judicial view of salvation that I had been teaching, based on Paul’s forensic metaphors in Romans, did not resonate in this Muslim setting. My assumption was that people were depending on their good works for forgiveness, but this was not necessarily the case. Their hope was in the mercy of a God who knows our weakness and is willing to forgo punishment. In Canada, we live in a guilt–innocence culture; sin is doing wrong against a moral code and we have a high regard for the rule of law. On the other hand, Pakistani Muslims live in a shame-honor culture.1 Forgiveness is always possible when a command is broken, but a person who dishonors their family faces disastrous consequences, often without the hope of redemption. I set aside a couple of days to wrestle with this question and discovered a perspective on the salvation of Christ that connects more closely with their felt need for a savior: through bearing the cross of shame (Gal 3:13), Jesus joins us in our separation from God. Because his relation to the Father has not been broken and he is alive with God, we can have a restored relationship with God by becoming “in Christ” (to use Paul’s phrase, eg. Rom 8:1).

Through this experience I realized that people with a history, culture and traditions unlike ours need to hear the message of salvation in a way that is relevant to them, a way that resonates with their sense of brokenness and need. The way we understand Jesus’ salvation in our setting may not connect with the view of reality in another setting. Effective communication means that the hearer understands within the categories they use to make sense of the world. By using words and concepts that they are familiar with, we are able to contextualize the gospel message.

Contextualization in Canada

Marie2 took a break from her emotionally taxing work at a charity in downtown Victoria to visit a family friend who made a comment about her spiritual search by means of an eastern meditation technique. Marie responded by asking, “Does that satisfy you?” The colleague was silent for a moment and then said, “Actually, no. It doesn’t.” The honesty of Marie’s friend has opened the door to further significant conversations, but where does she go from here? Would a description of the death and resurrection of Christ be accepted as the fulfillment of her colleague’s spiritual search? How is Marie to discover and communicate how the message of the gospel resonates with her colleague’s yearning?

Marie2 took a break from her emotionally taxing work at a charity in downtown Victoria to visit a family friend who made a comment about her spiritual search by means of an eastern meditation technique. Marie responded by asking, “Does that satisfy you?” The colleague was silent for a moment and then said, “Actually, no. It doesn’t.” The honesty of Marie’s friend has opened the door to further significant conversations, but where does she go from here? Would a description of the death and resurrection of Christ be accepted as the fulfillment of her colleague’s spiritual search? How is Marie to discover and communicate how the message of the gospel resonates with her colleague’s yearning?

When a Christian believer interacts with a person with different beliefs there are a number of barriers that must be crossed in order for them to converse intelligently about their respective faiths. Furthermore, intercultural encounters require lengthy and elaborate communication to facilitate reciprocal understanding. For example, an outline of the gospel that makes sense to the Christian will be met with incomprehension from a Muslim:

Christian: “Because Jesus died, we can be forgiven.”

Muslim: “But is not God free to forgive whomever he wants?”

This gap of understanding needs to be bridged by discovering how the cross of Christ resonates with the spiritual need of those who do not know Jesus.

Steps to Discover Gospel Resonance

Fortunately, there are steps that can be taken by the believer to make the gospel message comprehensible to a friend whose allegiance is with another faith. In Learning to talk ENGLISH, we considered four steps provided by Wen-Shu Lee that can help an English speaker converse comfortably with an ESL (English as second language) speaker.3 These same steps can be adapted to provide a process through which the gospel message can be shaped in a way that resonates with others.

Step 1. Establish a Conversational Etiquette that facilitates open dialogue about faith.

Younas sighed and looked ruefully at the end of his burning cigarette. He had given up drinking “bhung,” a narcotic, he had quit chewing betel nut, but he couldn’t give up smoking. Whenever I meet with Younas, we share our faith journeys with each other and through the drifting smoke we discussed some Sufi sayings that he found significant (Sufism is a mystical expression of Islam popular among the Sindhi people). On this occasion one of the sayings reminded me of a lesson from the Sermon on the Mount, and I showed him the Scripture passage. Laughing, he replied, “Every time I tell you a Sufi teaching, you are able to show me something similar that Jesus said.” I concurred and explained, “In the Bible it says that Jesus is the Word of God. He is the source of truth and all truth originates in him.” Our established conversational etiquette permitted us to be open with each other about our faiths.

Younas sighed and looked ruefully at the end of his burning cigarette. He had given up drinking “bhung,” a narcotic, he had quit chewing betel nut, but he couldn’t give up smoking. Whenever I meet with Younas, we share our faith journeys with each other and through the drifting smoke we discussed some Sufi sayings that he found significant (Sufism is a mystical expression of Islam popular among the Sindhi people). On this occasion one of the sayings reminded me of a lesson from the Sermon on the Mount, and I showed him the Scripture passage. Laughing, he replied, “Every time I tell you a Sufi teaching, you are able to show me something similar that Jesus said.” I concurred and explained, “In the Bible it says that Jesus is the Word of God. He is the source of truth and all truth originates in him.” Our established conversational etiquette permitted us to be open with each other about our faiths.

As emphasized in the articles on Significant Conversations, a conversation is not a battle to be won, but a pleasant interchange of ideas and experiences. The purpose should not be to establish superiority of belief. Such a stance will damage the relationship by initiating arguments, not conversations, about faith. Instead seek to establish an environment in which both faiths can be discussed, and be respected even in their differences. There are a number of actions that will ensure this:

- Listen to understand your friend’s faith, not to find weaknesses or inconsistencies.

- Articulate your friend’s faith back to them so that they are convinced that you not only understand what they believe, but appreciate this intimate part of their lives.

- Communicate your own faith with the goal of transparency so your relationship with your friend can deepen.

- Follow the ABC process: Agree, Build and Contrast (See article: Tools for Talking about Jesus).

- Don’t spend time developing arguments about why your faith is true, except where such concepts shape your life. Tell stories about how Jesus makes a difference in your life.

(For further discussion on ways to hold Significant Conversations see “God will not let me not into heaven”)

Step 2. Differentiate between explanations about faith and stories of personal faith

Joanne was adjusting her chair so she could better view the other members of the committee around the table when one of her colleagues declared, “I am a very spiritual person.” My friend was taken aback and interpreted this as arrogance and an expression of superiority, which is how it would be understood in our Christian or churched culture. She only realized later that her colleague was referring to a sensitivity to and interest in a reality beyond the material needs of life. Metatalk is important when conversing with people of other faiths in order to avoid misattribution: judging someone’s actions according to incorrect assumptions.4

Joanne was adjusting her chair so she could better view the other members of the committee around the table when one of her colleagues declared, “I am a very spiritual person.” My friend was taken aback and interpreted this as arrogance and an expression of superiority, which is how it would be understood in our Christian or churched culture. She only realized later that her colleague was referring to a sensitivity to and interest in a reality beyond the material needs of life. Metatalk is important when conversing with people of other faiths in order to avoid misattribution: judging someone’s actions according to incorrect assumptions.4

When discussing faith, communication needs to take place on two levels. The most important level is sharing stories of personal faith experiences. When we talk about what moves us spiritually, whether a passage of Scripture, appreciation for salvation in Christ or the intimacy of prayer, we are being transparent and vulnerable about who we are. This is what it means to be a “witness” to our faith.

However, a second level of metatalk is critical when speaking to someone of another faith. Metatalk happens when we step back from the content of the conversation and ensure that communication is actually occurring. Linguistic Metatalk occurs when we discuss the meaning of vocabulary and concepts to ensure a common understanding. A colleague related her frustration as a missionary in Latin America while dialoguing with nominal Catholics. Although the religious terminology was the same, the assumed meaning of the words was different which hampered communication. I have started to develop a new vocabulary to avoid using Christian words that tend to be misunderstood in the Canadian context. For example:

Instead of… I say…

Fear of God = don’t be careless with God

Sin = telling God “we can do better for ourselves than by following your way.”

Redemption = “there is a way to be good again”5

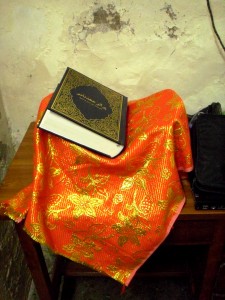

Relational  metatalk happens when we talk about the appropriate respect expected by each other when discussing spiritual things. For example, in Islam the physical Scriptures are sacred, not just the message, and must not be placed on the floor. The prophets’ names require titles of respect. The way God’s name is used needs clarification. A friend was talking to a Muslim woman who had learned English and was using the phrase, “Oh my God!” When he questioned her, she was devastated to learn that in many western contexts the expression is used as an expletive rather than a sincere reference to God. In her Islamic context, God’s name is constantly invoked with respect so that his presence is acknowledged. Metatalk provides a means to prevent inadvertent offense and discomfort.

metatalk happens when we talk about the appropriate respect expected by each other when discussing spiritual things. For example, in Islam the physical Scriptures are sacred, not just the message, and must not be placed on the floor. The prophets’ names require titles of respect. The way God’s name is used needs clarification. A friend was talking to a Muslim woman who had learned English and was using the phrase, “Oh my God!” When he questioned her, she was devastated to learn that in many western contexts the expression is used as an expletive rather than a sincere reference to God. In her Islamic context, God’s name is constantly invoked with respect so that his presence is acknowledged. Metatalk provides a means to prevent inadvertent offense and discomfort.

Step 3. Identify the spiritual yearnings of your friend.

a whole new doorway of understanding about how salvation can be communicated

Abdul Ali leaned towards me intently and responded to the story of Jesus washing the disciples feet. He said, “Jesus’ meaning, as far as I understand, is this. He was a prophet of God. According to this book and according to our faith, he was a beloved prophet of God. God gave him all knowledge to know who was true to him and who deceived him. So God gave him the wisdom to know how to make his followers holy. This means that there was a message here that Jesus said he would wash their feet and make them holy, that is, draw them towards him. With his hands he would wash the feet, make the person holy and so draw the person towards him.”6

I had never heard the washing of Jesus’ feet explained in this way, but at this point in our discussion the correct interpretation of the passage was not the point. I was discovering an aspect of the Sindhi culture that would open up a whole new doorway of understanding about how salvation can be communicated.

The way Jesus fulfills my spiritual longings will not necessarily reflect the way my friend finds Jesus relevant to his life. We cannot assume that what makes sense to us about salvation will resonate with those from another religious tradition. This was the primary discovery of the research project, Towards Contextualized Bible Storying: Cultural factors which influence impact in a Sindhi context. We need to first understand how people hear scripture from within their different culture setting in order to shape the gospel message in a way that connects with their worldview.

This is accomplished by listening carefully to our friends when they describe their faith. What are the spiritual yearnings that they hope will be fulfilled through the practice of their faith? How does their faith make a difference in their life? It is important at this stage to listen well to discover the stories, images and concepts that express their spiritual concern.

The concepts of “clean” and “unclean” as spiritual issues are lacking in our western society. In another story, when Jesus heals a woman of her constant bleeding (Lu 8:43-48), we are impressed with Jesus’ power and compassion. But the impact of Jesus reaching out his hand, touching the unclean and making them clean, is, for us, a minor part of the miracle. However, for those living in a culture like the Sindh, the state of being constantly unclean gives impact to the story. A woman in the Muslim Sindhi culture is not permitted to touch a holy book during her period. She cannot come into the presence of God because she is unclean, unfit for the holiness of God. Imagine 12 continuous years of separation from God! For the Sindhi reader, Jesus did not just heal a woman from a daily discomfort and medical distress, but released her from spiritual bondage and set her free to come into God’s presence. The concept of “unclean” for a Sindhi Muslim woman can reflect a deep spiritual longing that, when discovered, opens the door to the gospel.

Step 4. Demonstrate how Jesus addresses your friend’s spiritual desires

Manzoor raised his voice against the rattle of traffic outside the door as he related to me an expression of his faith in Jesus. He had recently donated one of his kidneys to his brother who had suffered kidney failure. After the operation, a number of people came up to him and said, “Because of that great sacrifice you are surely destined for heaven!” His reply was that his action was not the reflection of a desire for heaven, nor was it fit as credit for paradise. Instead, the action demonstrated his faith in Jesus. Jesus showed the way of giving up his life for the sake of others. Jesus’ death on the cross intersects with Manzoor’s life. Jesus’ sacrifice resonates with that expression of his faith. This powerful connection of the gospel with real life illustrates one way the gospel message has been contextualized into the Sindhi setting.

Manzoor raised his voice against the rattle of traffic outside the door as he related to me an expression of his faith in Jesus. He had recently donated one of his kidneys to his brother who had suffered kidney failure. After the operation, a number of people came up to him and said, “Because of that great sacrifice you are surely destined for heaven!” His reply was that his action was not the reflection of a desire for heaven, nor was it fit as credit for paradise. Instead, the action demonstrated his faith in Jesus. Jesus showed the way of giving up his life for the sake of others. Jesus’ death on the cross intersects with Manzoor’s life. Jesus’ sacrifice resonates with that expression of his faith. This powerful connection of the gospel with real life illustrates one way the gospel message has been contextualized into the Sindhi setting.

The final step to shape the gospel message in a way that fits the perspectives of others is to connect God’s word with the spiritual desires that have been identified in their lives. As we provide stories and examples of teaching from Scripture that connect with these desires, we illustrate how Jesus is relevant to them. Furthermore, illustrations from our friends’ own cultural context, such as in Manzoor’s example, can also reveal Biblical values. Discovering such stories will provide a clear connection between their spiritual yearnings and the Gospel message.

For the Sindhi Muslim, there are many connections between their lives and the gospel message: the sacrificial system, a concern for ritual purity, respect for God’s word, the importance of obedience and submission, the role of prayer in their relationship with God. Similar connections exist in Canada. Contextualization, whether in Pakistan or here in Canada, demands that we discover and understand the spiritual hungers that people have and then do the hard work of discovering how the gospel message can be communicated so that it resonates with those hungers.

Mark spends part of his time assisting churches in developing significant cross-cultural relationships. If you are interested, please contact him via the Contact Me form. If you would like to leave a comment about this article, please use the “comment” link at the bottom of this article.

____________________

- 1 Roland Muller proposes that each culture is influenced in different degrees by three dichotomies: Shame-honor, Guilt-innocence and Fear-power. See Muller, R 2000. Honor and Shame: Unlocking the Door. USA: Xlibris.

- 2 The names used in this article have been changed.

- 3 Lee, Wen-Shu 2000. That’s Greek to Me: Between a Rock and a Hard Place in Intercultural Encounters in Intercultural Communication: A Reader. 9th Ed. Samovar, Larry A. and Porter, Richard E. Eds. Belmont: Wadworth Pub, 222.

- 4 Patty Lane helpfully elaborates on misattribution and how it can be overcome in her book A Beginner’s Guide to Crossing Cultures: Making Friends in a multi-cultural world. IVP: Downers Grove, 27-30.

- 5 Husseini, K 2003. The Kite Runner. Canada: Random House, 2.

- 6 Naylor, M. 2004. Towards Contextualized Bible Storying: Cultural factors which influence impact in a Sindhi context. Unpublished: 68-69.