NOTE: A companion workshop to these articles is available to multi-ethnic churches that provides information, exercises and interaction so that those disciplines that promote healthy intercultural relationships can be implemented. Please contact Mark via the Contact Me form.

Multicultural Fragmentation

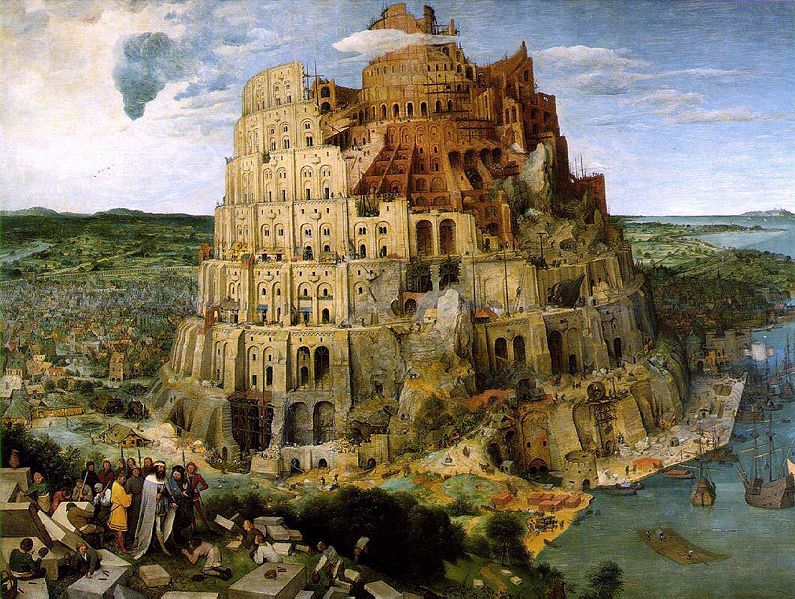

The story of Babel (Gen 11) records the story of the first failure of an intercultural enterprise. Since that time, history is replete with examples of multicultural endeavors that crumbled into monocultural fragments. On the day I write this – Feb. 16, 2008 – the morning news reported that Kosovo is declaring independence from Serbia, a division based to a large extent on cultural and ethnic distinctives. At the same time, the world population is on the move as never before, crossing geographical barriers and developing intercultural relationships. Ethnic groups who, in another age, would not have been aware of each other’s existence are living and working in close proximity to each other. Cities worldwide reflect the global phenomenon of ethnic diversity with mono- or multi-ethnic ghettos grouped together to create a montage of the broader reality. A short trip in the transit system of BC’s lower mainland exposes the rider to a variety of color, languages and accents.

The story of Babel (Gen 11) records the story of the first failure of an intercultural enterprise. Since that time, history is replete with examples of multicultural endeavors that crumbled into monocultural fragments. On the day I write this – Feb. 16, 2008 – the morning news reported that Kosovo is declaring independence from Serbia, a division based to a large extent on cultural and ethnic distinctives. At the same time, the world population is on the move as never before, crossing geographical barriers and developing intercultural relationships. Ethnic groups who, in another age, would not have been aware of each other’s existence are living and working in close proximity to each other. Cities worldwide reflect the global phenomenon of ethnic diversity with mono- or multi-ethnic ghettos grouped together to create a montage of the broader reality. A short trip in the transit system of BC’s lower mainland exposes the rider to a variety of color, languages and accents.

Despite daily contact between ethnic groups, barriers of language, history, values, priorities and beliefs create emotional distance, misunderstandings and tensions that result in uneasy interactions. The church of Jesus Christ has responded to this ethnic variety in a number of ways. Guided by multicultural visions found in the Bible, such as the event of Pentecost and John’s vision in Revelation 7, many congregations seek to establish multi-ethnic expressions of the body of Christ. Unfortunately and inevitably, tensions arise and sometimes Babel repeats itself with the failure of the multicultural enterprise and a fragmentation into monocultural groups.

power distance [is] a primary cause of intercultural tensions

This series of articles analyzes the reason for these intercultural tensions and explores ways to resolve them in a way that strengthens the unity of the church. A variety of models that churches can adopt to set an intercultural agenda for their congregations have been explored elsewhere. 1 In this article I would like to explain power distance as a primary cause of intercultural tensions, and in the following articles propose an important discipline that will allow those tensions to be successfully overcome.

Power Distance

High Power Distance cultures (HPD), such as in Korea, India and the Philippines, for example,

…accept that inequalities in power and status are natural or existential. People accept that some among them will have more power and influence than others in the same way they accept that some people are taller than others. Those with power tend to emphasize it, to hold it close and not delegate or share it, and to distinguish themselves as much as possible from those who do not have power. They are, however, expected to accept the responsibilities that go with power, especially that of looking after those beneath them. Subordinates are not expected to take initiative and are closely supervised.2

In contrast Low Power Distance cultures (LPD), such as in Canada and Australia, for example,

…see inequalities in power and status as man-made (sic) and largely artificial; it is not natural, though it may be convenient, that some people have power over others; Those with power, therefore, tend to deemphasize it, to minimize the differences between themselves and subordinates, and to delegate and share power to the extent possible. Subordinates are rewarded for taking initiative and do not like close supervision.3

HPD: stability is established through clear and constantly reinforced hierarchical relationships

In HPD cultures, stability is established through clear and constantly reinforced hierarchical relationships and unspoken rules of personal interaction. Outsiders who fail to follow the rules or undermine the structures in any way are considered rude, ignorant and even dangerous. Because such cultures are usually concerned with issues of honor and shame, such inappropriate action is not addressed directly, but through subtle and indirect gestures – such as protesting through silence – that the member of the LPD culture is usually incapable of perceiving. Maintaining harmony in relationships is a priority and competition is avoided through communal agreement of a person’s place in the hierarchy. A redistribution of power is not valued and is seen as a disruption of the stability and order of society, although people do move into positions of power through accepted channels (e.g., becoming an elder or through inheritance).

LPD: stability is established through insistence on equality, individual rights and the rule of law

In LPD cultures, stability is established through insistence on equality, individual rights and the rule of law. Clarity, reason and directness are tools used to evaluate each situation and mutually agreed upon solutions are sought through open, frank and detailed discussion with all parties. When disagreements cannot be resolved, a vote is taken and the majority rules. Competitiveness is encouraged with the belief that the process is productive, disputes should not be taken personally and resolution is ultimately possible, even though it produces winners and losers. Redistribution of power is valued and such negotiations and struggles are seen as a healthy part of societal interactions. A level playing field is considered essential where the entrepreneur or innovator can excel.

This clash of values causes the primary source of tension when LPD and HPD cultures meet with the desire to work together, such as in a multicultural church setting.

Examples of High Power Distance cultures and Low Power Distance cultures

Eric Law provides an comparative list of High verses Low Power Distance Countries taken from data collected by Hofstede 4:

| High Power Distance | Low Power Distance |

| Philippines | Austria |

| Mexico | Israel |

| Venezuela | Denmark |

| India | New Zealand |

| Singapore | Ireland |

| Brazil | Sweden |

| Hong Kong | Norway |

| France | Finland |

| Colombia | Switzerland |

| Turkey | Great Britain |

| Belgium | Germany |

| Peru | Australia |

| Thailand | Netherlands |

| Chile | Canada |

| U.S.A. |

It needs to be kept in mind that this contrast should be understood as a generality – especially when referring to countries rather than people groups – and some countries will show a greater tendency to the indicated orientation than others.

Examples of the Clash between High Power Distance cultures and Low Power Distance cultures

1. This clash of values can be illustrated by the different view of money between HPD and LPD cultures. In Europe “old money” is valued. Through inheritance of both title and wealth, the nobility maintain a status of belonging to a people of “quality,” despite the fact the heir may not accomplish anything of practical value. In North America, however, it is “new money” that is admired. To have gone from “rags to riches” is paraded as an accomplishment, whereas inherited money does not have the same air of respect.

2. During my time in Pakistan, an employee made a personal threat on my life due to a decision made in the course of my duties. Because this was considered too serious to ignore, a mediator was brought in who was related by marriage to the employee. Our missions chair and I met with the mediator who suggested that such language as used by the employee should not be taken too seriously. I asked him what language would warrant action and he deflected my question with similar comments about not reading too much into the situation. Because he hadn’t addressed my question, I repeated my question and he again deflected the issue. I persisted and asked the question a third time. This time he unexpectedly exploded in anger – unexpectedly, for the tone of the conversation was congenial – and berated me for my arrogance and pride. My problem, however, was not arrogance but insensitivity to the rules of a HPD culture. His deflection of my question was a signal that I was leading the discussion in an awkward direction that would not lead to proper resolution. However, with my LPD cultural perspective, I was unable to pick up on the subtle hint and insisted on dealing with the issue directly, a method that, in the opinion of our mediator, would have resulted in a greater breakdown of relationships.

3. At one orientation to ACTS seminaries for new students that I attended, the professors engaged in light banter with each other, calling each other by their first name. This is typical LPD culture communication seeking to downplay the distance between the professor and the student, establish an ethos of equality and togetherness and indicate that relationships can be friendly and open. However, I sensed discomfort on the part of those students who had come to Canada from HPD contexts. Rather than communicating a stable hierarchical environment with clear roles, the lack of respect for titles and undermining the status of professor was disconcerting to them.

4. Lanier, in her book Foreign to Familiar, provides a telling illustration when teaching a multicultural class in India. She offered an optional class on a particular subject for those who were interested. She reports, “Of the one hundred and fifty or so students, about twenty-five were Koreans. To my surprise, they all showed up. Some were obviously tired, yet they came. Later, I realized they came because the teacher invited them. They could not disappoint the teacher by not coming”5. Respect for the teacher was required, and non-attendance from the Korean contingent would have, in their minds, communicated a lack of respect.

The Doom of Babel

Without an understanding of the dynamic of power distance that occurs within intercultural relationships, a multiethnic church cannot succeed. The doom of Babel is not the diversity of languages and cultures. That diversity is a blessing from God providing a kaleidoscope of windows onto reality to enrich the cultural traveler who learns to see life through another’s eyes. As Charlemagne said, “To possess another language is to possess another soul.” Rather the doom of Babel is the inability to overcome the barriers that separate ethnic groups so that unity in diversity can be achieved. For the Christian, Pentecost becomes the promise of that unity: diversity retained and valued, yet with the ability to become “one.”

In the next article I will elaborate on the concept of power distance to explain the struggles of leadership within HPD and LPD settings. A further article will provide a solution to intercultural tensions by proposing a discipline of speaking and hearing the language of respect used within the other cultural orientation. Finally, Eric Law’s innovative method of “mutual invitation” will be explored as a method of developing productive interaction in order to bridge the power gap between HPD and LPD cultures.

Mark spends part of his time providing churches workshops in developing cultural sensitivity. If you are interested please contact him via the Contact Me form. If you would like to leave a comment, please use the “comment” link at the bottom of this article.

____________________

- 1 See Navigating the Multicultural Maze in Being Church: Explorations in Christian Community, published by Northwest Baptist Seminary, 2007, pp. 13-42 and the workshop Intercultural Church Dynamics described in the CILD Seminars.

- 2 Storti, Craig. 1999. Figuring Foreigners Out: A Practical Guide. Yarmouth: Intercultural Press. p. 130.

- 3 ibid. p. 131.

- 4 Law, Eric. 1993. The Wolf Shall Dwell with the Lamb. St. Louis: Chalice Press. P. 22.

- 5 Lanier, S. 2000. Foreign to Familiar: A Guide to Understanding Hot- and Cold- climate Cultures. Hagerstown: McDougal Pub. p. 94-95.