NOTE: A companion workshop to these articles is available to multi-ethnic churches that provides information, exercises and interaction to encourage the implementation of those disciplines that promote healthy intercultural relationships. Please contact Mark via the Contact Me form.

The High Power Distance / Low Power Distance1 Culture Clash

HPD = High Power Distance LPD = Low Power Distance

When people of the lower classes visit a medical doctor in Pakistan, they are very reticent to ask the doctor to provide an explanation for the prescriptions given, and often remain unaware of the nature of their illness, considering it sufficient to follow the doctor’s instructions. To ask for reasons would be tantamount to questioning the doctor’s competence and therefore impolite. The role of leaders as the decision makers together with the submissive, obedient attitude of followers is typical of High Power Distance (HPD) cultures.

Among the Sindhi people of Pakistan2 a popular Sufi story is told to illustrate the virtue of meekness. A king had a servant that he loved above all others, and seeing this the other servants became extremely jealous. The king was not unaware of the situation and one day he called his servants together and placed a valuable jewel before them. “Take a hammer and destroy this jewel!” he commanded. The servants looked at each other in shock and began to protest. “But Sire, this is extremely valuable. We don’t want to destroy such a precious treasure!” The king then turned to the servant he loved and gave the same command. The servant immediately seized a hammer and shattered the precious stone. The king then turned on his servant and rebuked him. “Why did you do that? Don’t you know that this was a valuable jewel? You have destroyed it beyond repair!” At once the servant bowed his head and said, “I’m sorry. You are right. I should not have done that.”

Among the Sindhi people of Pakistan2 a popular Sufi story is told to illustrate the virtue of meekness. A king had a servant that he loved above all others, and seeing this the other servants became extremely jealous. The king was not unaware of the situation and one day he called his servants together and placed a valuable jewel before them. “Take a hammer and destroy this jewel!” he commanded. The servants looked at each other in shock and began to protest. “But Sire, this is extremely valuable. We don’t want to destroy such a precious treasure!” The king then turned to the servant he loved and gave the same command. The servant immediately seized a hammer and shattered the precious stone. The king then turned on his servant and rebuked him. “Why did you do that? Don’t you know that this was a valuable jewel? You have destroyed it beyond repair!” At once the servant bowed his head and said, “I’m sorry. You are right. I should not have done that.”

Then the king looked at his other servants and revealed his lesson. “This is why I love this servant more than any other. I commanded and he obeyed. I rebuked and he did not defend himself.”

Then the king looked at his other servants and revealed his lesson. “This is why I love this servant more than any other. I commanded and he obeyed. I rebuked and he did not defend himself.”

In the high power distance context of the Sindh, the relationship between the master and the servant is praised and considered worthy of emulation. However, in a Low Power distant (LPD) culture, such as Canada, this story appears to promote an abusive and improper relationship that should be corrected, not emulated!

When LPD and HPD cultures meet with the desire to work together, such as in a multicultural church setting, there is inevitable tension due to the clash between these two very different orientations.

Navigating the Clash through their “language” of respect

Leaders of multi-ethnic3 churches who take seriously their responsibility to guide the congregation towards healthy intercultural relationships must successfully navigate these two diverse and often conflicting orientations. While it is important for the leader to understand the dynamics at play within the group, how people’s orientation affects their actions and the perception of the actions of others, and how to recognize the way these tensions are expressed (see previous articles), it is even more important to know how to cultivate an environment of graciousness and understanding that will allow these tensions to be resolved. An important step in achieving this is learning to hear and speak the “language” of respect used by those of the opposite orientation.

learn to hear and speak the “language” of respect

By “language” I refer metaphorically to the culturally defined actions and behaviors by which people express respect for others. Even when a common language of communication is used, such as English, the cultural cues, e.g., body language, are often not translated. These cultural expressions of respect are difficult to reformat into another culture’s perspective because they express values and beliefs important to the people of that cultural group. For example, even though I know that in Pakistan people crowd around and reach in to buy their train tickets, I still feel annoyed when someone “butts in front” of me because of my cultural preference not to be aggressive and to take turns in an equitable manner. I tend to misattribute4 or judge their action according to my frame of reference concerning what is appropriate and respectful.

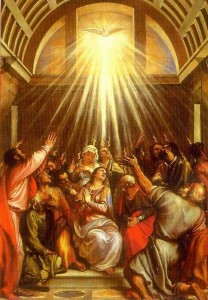

Practicing Pentecost

Eric Law points out that most people view the event of Pentecost (Acts 2:1-7) as a miracle of speaking in tongues. What is often overlooked is the second half of the miracle: people were also hearing in their own language5. This communication of both speaking and hearing is an appropriate metaphor for the intercultural discipline of learning the language of respect of other ethnic groups. Success in navigating intercultural relationships is dependent upon the practice of hearing and speaking the other’s language of respect. Without this discipline intercultural tensions will not be appropriately addressed and cultural barriers will be strengthened rather than overcome.

Eric Law points out that most people view the event of Pentecost (Acts 2:1-7) as a miracle of speaking in tongues. What is often overlooked is the second half of the miracle: people were also hearing in their own language5. This communication of both speaking and hearing is an appropriate metaphor for the intercultural discipline of learning the language of respect of other ethnic groups. Success in navigating intercultural relationships is dependent upon the practice of hearing and speaking the other’s language of respect. Without this discipline intercultural tensions will not be appropriately addressed and cultural barriers will be strengthened rather than overcome.

One day when walking to a friend’s house in Larkana, Pakistan, with my wife, Karen, a friend met me on the road. He briefly greeted me and without once glancing at or acknowledging Karen’s presence moved on. Karen responded by exclaiming to me, “What a polite man!” This was an honest comment, not sarcasm. What my friend had done was treat Karen and me with respect. In the Sindhi context a polite man does not take notice of or acknowledge another man’s wife unless they have been properly introduced and the setting is considered appropriate. In Canada, his action would have been considered rude and demeaning. However, we had been in Pakistan long enough to be able to read and appreciate the Sindhi language of respect.

Talking the talk is walking the walk

It is important to realize that this principle is not simply an exhortation to treat each other with respect. Respect in a church context is a given. But it is not sufficient to treat people of another ethnic group in ways that we consider respectful. We must also learn how they express respect (hearing the language) and then practice those expressions when in their company (speaking the language). When people greet, do they bow, shake hands, hug, kiss? What is the difference in greetings between genders, strangers and friends, children and the elderly? In Pakistan greetings are an essential part of expressing respect. Standing up to greet someone, the physical contact (handshake, half hug, full hug), the length of greeting, all speak about the relationship and how people are viewed.

Learning another language is never easy, but the attempt in itself is an expression of respect. In Pakistan, men frequently walk down the street holding hands as a common expression of friendship. I remember the first time a friend took my hand as we were walking down the street. I tensed up inside because of the message conveyed in my cultural background, but I didn’t pull away. I was determined to learn this language of friendship and use it.

Learning another language is never easy, but the attempt in itself is an expression of respect. In Pakistan, men frequently walk down the street holding hands as a common expression of friendship. I remember the first time a friend took my hand as we were walking down the street. I tensed up inside because of the message conveyed in my cultural background, but I didn’t pull away. I was determined to learn this language of friendship and use it.

Colleagues of ours in Pakistan went home to Virginia, U.S.A. for a visit. Their son of about 8 years had grown up in Pakistan and had not learned the ways of relating in his home state. He took some candy up to a store counter with his money explaining to the clerk that he wanted to buy the candy. The man refused to take the money and make the purchase because the boy had failed to address him as “sir”! Our colleague’s son had no intention of being rude, but he had failed to speak the language of respect expected in that context.

I had failed to speak their language of respect

We had a small fellowship of believers during our time in Larkana. One day after a worship service I chatted with a couple of newcomers and then took them out for a meal. When I returned I discovered that those left behind were very angry that they had not been invited to the meal. The issue was not a matter of food, or an unreasonable expectation that I should feed everyone present. Rather, the way I had excused myself and taken the two guests to lunch had inadvertently communicated rejection and disrespect. I had failed to speak their language of respect. It was not enough that my intentions were good and that I had no desire to insult anyone. In order to “walk the walk” and communicate the love and acceptance of Christ we also need to learn to talk their talk.

Love is the motivation to learn another’s language of respect

It is important for leaders in a multicultural church setting to promote on an ongoing basis the reality that learning another’s language of respect is an act of love. It is easy to become defensive and protective of our own way of doing things, especially when it viewed as the “right” way of doing things. “If they can’t understand how we do it, then they will just need to learn!” tends to be the attitude. But to demand that others adapt to our way of doing things often undermines the possibility of healthy intercultural exchange. It expresses a lack of love, that is, a lack of willingness to sacrifice our own comfort and sense of appropriateness in order to communicate effectively.

During an Intercultural Health workshop that I was leading, a woman expressed her discomfort with people who wasted food by not eating everything on their plates. A time of severe deprivation in her past had taught her to value God’s provision and therefore her language of respect and thankfulness was to ensure that nothing was thrown away. In reply, it was explained that for some cultures leaving a bit of food on the plate was an expression of gratefulness and showed that the host had provided for them over and above their need. Hearing this, the woman responded, “But can’t they learn not to waste food since that isn’t the message we understand?” We talked about how difficult that would be for them by comparing her discomfort if she was required to leave food on her plate in order to communicate appreciation to her host.

During an Intercultural Health workshop that I was leading, a woman expressed her discomfort with people who wasted food by not eating everything on their plates. A time of severe deprivation in her past had taught her to value God’s provision and therefore her language of respect and thankfulness was to ensure that nothing was thrown away. In reply, it was explained that for some cultures leaving a bit of food on the plate was an expression of gratefulness and showed that the host had provided for them over and above their need. Hearing this, the woman responded, “But can’t they learn not to waste food since that isn’t the message we understand?” We talked about how difficult that would be for them by comparing her discomfort if she was required to leave food on her plate in order to communicate appreciation to her host.

“why don’t they change and conform!”

To leave some food on her plate would be a difficult expression of love and sacrifice on that woman’s part, but necessary if she wants to speak that ethnic group’s language of respect. Similarly, those who find it difficult to eat all the food and not leave anything would be required to alter their practice in order to communicate respect to people like that woman. The key is to learn another’s language of respect out of a motivation of love. Instead of thinking, “why don’t they change and conform!” the motivation of love asks, “how can I speak their language of respect?” Learning to speak someone else’s language of respect is a practical means of living like Christ and fulfilling the law of love.

How to Discover another Language of Respect

During a Portfolio of Cross-Cultural Experiences meeting, a Korean man expressed his offense at the Canadian practice of cleaning our noses with a handkerchief in public. While considered appropriate in a Canadian setting, this seems rude and unhygienic to Korean sensibilities, particularly at the dinner table. But how would a Canadian discover this perspective since Koreans would not make a guest or host lose face by addressing such behavior?

During a Portfolio of Cross-Cultural Experiences meeting, a Korean man expressed his offense at the Canadian practice of cleaning our noses with a handkerchief in public. While considered appropriate in a Canadian setting, this seems rude and unhygienic to Korean sensibilities, particularly at the dinner table. But how would a Canadian discover this perspective since Koreans would not make a guest or host lose face by addressing such behavior?

Consider these practical suggestions to discover and explore another ethnic group’s language of respect:

- It is often awkward and unproductive to discuss the perception of a behavior, such as the example given above, in a context where people will lose face. Instead, create forums or opportunities in which the issue can be raised in an impersonal or indirect manner. For example, to ask “what do you consider rude that other ethnic groups seem to accept as normal behavior?” as a point of discussion, can result in profitable insights. As long as individuals are not directly implicated there is no danger that anyone will lose face.

- Develop a close friendship with someone from the other ethnic group who will be open and honest about how an outsider should act so that people will believe that you respect, value and care for them. The friendship needs to be at such a level of trust that the insider will be able to be direct with you about cultural faux pas that you may inadvertently commit. I have such a friend in the Sindh who has saved me numerous times from cultural offenses.

Utilize “bridge” people. Bridge people are those children, born to immigrants, who have grown up in the Canadian context and thus are fully bi-cultural. Moving back and forth from their cultural home setting to the contrasting culture in the community during their adolescent years has given them a cultural sensitivity that can be a great asset to church leaders who want to develop healthy intercultural relationships.

Utilize “bridge” people. Bridge people are those children, born to immigrants, who have grown up in the Canadian context and thus are fully bi-cultural. Moving back and forth from their cultural home setting to the contrasting culture in the community during their adolescent years has given them a cultural sensitivity that can be a great asset to church leaders who want to develop healthy intercultural relationships.- Be observant of and sensitive to any tensions that may have a cultural cause. This includes keeping your antennae up for judgmental and defensive comments: “I was being polite,” “Who does he think he is?” “Why should we have to change for him?” “I don’t see why he got so upset!” etc. Such statements are often an indication that the person has misread an action due to their cultural orientation or has failed to speak the “language” that communicates respect.

- Go beyond the passive and safe approach of being on the outside and just observing. Intercultural tensions seldom go away by themselves. They are often internalized as hurts and can be destructive to the unity in the body of Christ. Be proactive and within appropriate contexts explore the reasons for any observed tension. This will often require the help and support of respected leaders who are insiders to the ethnic group.

Facilitating discussion and input

As mentioned in a previous article, it can be difficult to facilitate discussions and decision making in a group setting, such as a business meeting, in which there are there is a mix of both HPD and LPD culture oriented people. Is there a way to conduct business so that there is a level playing field and people of both orientations can feel that their participation has been appreciated and that they have been heard?

In the next and final article on High verses Low Power Distance orientations, Eric Law’s innovative method of “mutual invitation” will be explored as a method of developing productive interaction in order to bridge the power gap between HPD and LPD cultures.

Mark spends part of his time providing churches workshops in developing cultural sensitivity. If you are interested please contact him via the Contact Me form. If you would like to leave a comment, please use the “comment” link at the bottom of this article.

- ____________________

- 1 The first article in this series, 60. Resolving Intercultural Tensions 1: Power Distance, provides an explanation of High and Low Power distance cultures.

- 2 Karen and I worked among the Sindhi people of Sindh, Pakistan for 14 years with FEBInternational.

- 3 In these article, Multi-ethnic refers to a group of people in relationship with each other with a focus on their ethnic identity. Multicultural describes a group of ethnically diverse people in relationship with each other with an emphasis on their cultural orientation. Intercultural is used to refer to the interaction between ethnic groups. Cross-cultural refers to a person from one cultural orientation engaging a group of people with a different cultural orientation.

- 4 In A Beginner’s Guide to Crossing Cultures, Patty Lane explains misattribution as “attributing meaning or motive to someone’s behavior based upon one’s own culture or experience.” (InterVarsity Press, 2002) p. 27.

- 5 Law, Eric. 1993. The Wolf Shall Dwell with the Lamb. St. Louis: Chalice Press. p. 46.