An Inward or Outward focus?

Hudson Taylor was a pioneer missionary to China who recognized the need to immerse himself in the Chinese culture in order to relate the gospel to the people in ways that made sense to his audience. He learned their language, wore his hair in a pigtail, wore their clothes and, in general, lived his as close to their lifestyle as possible. According to some of his European colleagues, this was inappropriate. Because the Bible had been in their culture for so many centuries, they reasoned, their cultural values and norms were the true expressions of Christian life and universal for all cultures. Hudson Taylor disagreed. Rather than requiring people to become like him, he deliberately sought to become like them. Rather than “bringing people in” to meet Christ, his goal was to bring Christ into their lives. Such thinking represents the heart of the missional church.

When Karen and I lived in Pakistan1 we worshipped with the Baptist church located across the road from our residence. I had a sincere young Muslim ask to attend the worship service, so I took him with me. Afterwards I was taken aside by an elder and told that this was inappropriate: the young man was not a Christian, he was not baptized, he didn’t belong. Some time later the man was baptized, but not in that church. I took him again to a worship service in the church and the same elder took me aside once more. I explained that the young man was now baptized. The elder asked, "What is his name? Where does he live?" I told him the man’s name and that he lived with his father. The elder responded by explaining that until the man changes his name to a Christian name, and until he leaves his Muslim community and joins the Christian community, he cannot attend the church.

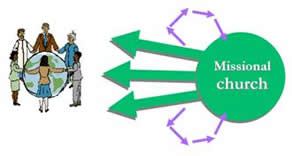

The point here is not to criticize the elder for this attitude because there are complex cultural issues that need to be understood. However, what is pertinent is the "bring them in and make them like us" mentality, an inward focus that is also prevalent in many Canadian churches. We are good at sending missionaries, we are good at bringing people into our meetings (very few churches would deny Muslims entry), but there is often a lack of conviction that we are a people who have "been sent" by Jesus to make the gospel relevant to others where they live. When churches talk of “outreach” a primary goal is usually to bring them in and assimilate them into church life. In contrast, we had gone to Pakistan with an outward focus. We attempted to learn what it means to live in a relevant Christ-like way in their culture, from the standpoint of their worldview, rather than conforming them to our culture and worldview.

There are two ways to be a church involved in God’s mission to the world:

There are two ways to be a church involved in God’s mission to the world:

1. Bring them in so they can assimilate (communal orientation) OR

2. Appreciate and interact with people in their context so they can experience the way Jesus relates to them where they live (missional orientation).

2. Appreciate and interact with people in their context so they can experience the way Jesus relates to them where they live (missional orientation).

Jesus’ Incarnation is the basis for Missional Orientation

Jesus’ incarnation, “God with us,” is the “theological prism through which we view our entire missional task in the world”2. In his high priestly prayer Jesus said, “As you (God) sent me into the world, so I send them (disciples) into the world” (Jn 17:18). Jesus came to make a difference in people’s lives by becoming like them. We are also called to be like Jesus and make a difference in people’s lives. Like Jesus this requires the maintenance of a paradox: becoming like others in order to be a transforming catalyst. Gospel transformation occurs through the cultural values and perspectives of a people group rather than by insisting on our own cultural norms. The missional church follows Jesus’ method of relating the gospel message to people’s lives within their context.

This biblical perspective of how God interacts with humanity contrasts sharply with Islamic theology. In Islam there is no accommodation of God towards humanity. God never becomes immanent with people, as in the incarnation. He is immovably transcendent. Thus, in their view of scripture, the Koran was dictated in heaven and handed down to the prophet. There is no human hand or culture involved in providing God’s revelation to humanity. It remains transcendent and pure. In contrast the biblical picture is of a God who speaks in and through human cultures, in and through human languages. Unlike the Koran, the Bible can be translated into other languages and remain the authoritative word of God. The ultimate accommodation to human frailty is found in the person Christ, the Word of Life seen with human eyes and touched with human hands (1 Jn 1:1).

God became human within a particular context, for our sake. Similarly, Jesus sends us, so that he can become Lord in many different contexts. The New Testament does not provide a blueprint for a universal form of church for all cultures to which people must accommodate. Rather the descriptions of church development and instruction reveal the missional understanding of the disciples who “worked out” the gospel message in their 1st century culture. The function of the church (e.g., fellowship, worship, teaching) was fulfilled through the cultural patterns with which the apostles were familiar. Proponents of missional churches believe that they are called to do the same: to work out salvation in other contexts using those forms that best express the message.

The Incarnation of the Gospel not the Messenger

It is important to recognize that the incarnational implications of the missional orientation do not require that the messenger literally become a full member of another culture, but that they work towards the gospel becoming an integral expression of another setting. While missionaries in Pakistan, we did not become Pakistani. That was impossible and, because of our own cultural values and priorities, would have been inappropriate if we had attempted it. When Paul spoke of becoming “like a Jew, to win the Jews” and becoming “all things to all people” (1 Cor 9:19-22), he was not speaking incarnationally, but from a desire to accommodate his practices and priorities for the sake of the gospel.

Similarly, our goal was to relate to the Sindhi people in such a way that they would recognize the gospel not as an imported western religion, but as God speaking to and relating to their lives. As foreigners, we understood and lived the gospel from within our cultural perspective because that is the means by which the gospel message is significant to us. What was required was an introduction of the gospel expressed relevantly within their cultural perspective. This involved a resolute investment in relationships with people and sensitivity to their context. We had to leave our “comfort zone” and learn to appreciate a very different perspective on life and relationships. However, the goal was not our incarnation into their reality, but the incarnation of the gospel of Christ. This is commonly referred to as a contextualization of the gospel message so that significance of the death and resurrection of Christ impacts both individual lives and the broader community in such a way that it is identified as integral to the culture.

The following article will provide a brief overview of how the missional concept has been developed by influential missiologists.

- _______________

- (1) From 1985-1999 Karen and I lived with our family as FEBInternational missionaries in Pakistan.

- (2) M. Frost & A. Hirsch, The Shaping of Things to Come: Innovation and Mission for the 21st Century Church (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), 35.