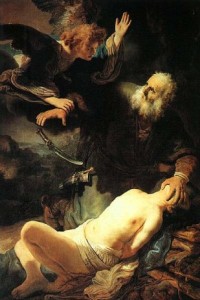

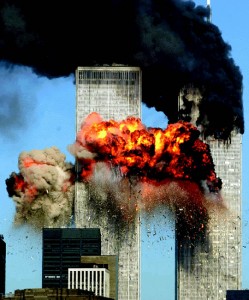

What kind of God commands people to strap bombs to their bodies and blow up crowds of people? What kind of God tells people to drive passenger planes into the sides of buildings? What kind of God commands parents to kill their children? What kind of God would come to one of his worshippers and say, “Take your son, your only son, whom you love – Isaac – and … sacrifice him…” (Gen 22:2)?

Those of us who believe in God as the loving father of the Lord Jesus Christ quickly rise to the challenge these questions represent and protest that the latter question is in a different category than the first three. There is a fundamental difference between the God of the Old Testament and the God of terrorists. Nonetheless, I suspect that the average churchgoer would find it hard to provide a defense or articulate a reasonable distinction. Furthermore, most outsiders to the faith, reading the Genesis passage, would likely categorize the God of Genesis 22 with the God of the first three questions. One friend of mine described God as “despot” and the Bible as “full of terrors” because of passages such as the sacrifice of Isaac.

In fact, skeptics often like to pose the question: “Suppose that God told you to kill your child…. If you are a God-Fearing Christian, do you have any theological grounds for refusing to kill your own child?”1 The correct answer to this question for Christians is to deny that the God of the Bible would require this, and to provide legitimate theological grounds for refusing to do such an evil deed. But such theology needs to be explained in light of Genesis 22, not by ignoring it.

A theology about the Bible

I believe that part of the reason for this uncomfortable comparison of the God of the Bible, particularly the Old Testament, with the God of terrorists is an inadequate theology about the Bible. In speaking of a theology about the Bible, I am not referring to a biblical theology, that is, a description of God and his relationship to humanity developed from an understanding of biblical content. Rather, I am referring to an understanding concerning how the Bible functions in shaping our faith.

Wm. Smalley provides a description of how the Bible is used and viewed by people around the world. Some approach the Bible as a cultural artifact of the Christian religion. Others make magical use of the Bible and view it as a fetish. For many people the Bible is primarily a law book to be obeyed. Another use of the Bible is as textbook to provide information. Others use the Bible as a reference, to answer the questions they have. Another use of the Bible is as a behavioral manual, a guide in developing moral practice. A common use of the Bible is as a devotional book, a book of worship. For many people the Bible is an oracle, through which they hear God speak.2

the Bible should be primarily viewed as revelation of the character, nature and will of God

Without denying the validity of some of the uses mentioned, I would argue that the Bible should be primarily viewed as revelation of the character, nature and will of God. We need to the approach the Bible for the purpose of understanding who God is and how he relates to us. It is only through the formulation of biblically shaped perspective of God that we can comprehend who we are: people created in his image. Genesis 22, then, is not a passage that we are to explain away in order to preserve a prior concept of God, but one through which we develop a better understanding of the God we worship. However, in order to do this, we must view the passage through the correct “lenses.”

Developing the right exegetical “lenses”

The Islamic understanding of their sacred scriptures, the Koran, is that it is a book that was written in heaven and then dictated to the prophet Mohammed. It is a book that is 100% divine without any human participation. Thus, it is pure and holy and untranslatable. The story is told of a journalist who approached a Muslim cleric and asked for a translation of the Koran that he could read in order to understand it. He was told, “There is no translation of the Koran. You must learn Arabic!”

The Islamic understanding of their sacred scriptures, the Koran, is that it is a book that was written in heaven and then dictated to the prophet Mohammed. It is a book that is 100% divine without any human participation. Thus, it is pure and holy and untranslatable. The story is told of a journalist who approached a Muslim cleric and asked for a translation of the Koran that he could read in order to understand it. He was told, “There is no translation of the Koran. You must learn Arabic!”

The Christian view of the Bible is different. Christians also believe that the Bible is 100% divine. But it is also 100% the product of human beings, albeit in a different way. God teaches us his truth, but it only occurs through human language, human understanding and human culture. In order to communicate, God accommodated to people, he did not command that they accommodate to him. “Prophets, though human, spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Peter 1:21 TNIV). Moreover, the incarnation is the ultimate accommodation to our need: “The Word became flesh” (John 1:14 TNIV). It is the realization that God spoke to people within their language, within their perspective of the world, and within their culture and worldview, that provides the basis for Bible translation. The divine message can be represented in any language, because the original is also not a divine, but a human language.

The divine message can be represented in any language

Furthermore, this human cultural dynamic of the biblical passage provides us with the “lenses” through which we can properly understand what on earth God was doing when he said to Abraham, “Sacrifice your son.”

Cultural Contrast

Abraham was surrounded by gods. He was in Canaan and the Canaanites had many gods: mountain gods, river gods, fertility gods, and gods of war. Abraham’s understanding of the gods came from the context in which he lived. His relationship and response to the God who had chosen him was shaped by the worldview that he lived in. For the people of that time, the most powerful god could do the greatest things, and the most powerful god demanded the greatest sacrifice. Some of those gods demanded human sacrifice – Molech is the best known – because they demanded the best.

It may have been a surprise to Abraham to receive this command. But, as far as Abraham knew, it was not out of character for the way gods acted. He wasn’t shocked. He didn’t go through a lot of soul searching. He didn’t argue with God. He didn’t look for a way out. Instead, “early the next morning” he set out to fulfill this command. Why would he do this? Because in Abraham’s world this was consistent with the way gods acted. The greatest god demanded the greatest sacrifice, and God was proving to Abraham that he was the greatest God. Abraham obeyed without question, because that was the response required by his cultural setting and by his vow to be the servant of this God.

However, from our modern Canadian perspective, the scenario is strange and perverse. If this happened to us, we would question it. We would look for a second opinion. We would doubt our sanity. We would do all we could to get out of this dilemma, because it doesn’t make sense. This is not the God we know. The story makes no sense to us in our culture because we understand God in Jesus Christ – a God who loves and redeems, not one who destroys. My friend looks at this story and sees a god of terror, a vindictive and a cruel god. And I know why, because I live in the same culture and see things the same way.

But for Abraham, this scenario fit perfectly in his world. This was how gods acted. This story made perfect sense to Abraham because it was played out over and over again in human sacrifice all around him. This, for Abraham, was normal. God was speaking Abraham’s language.

What Abraham didn’t know, and needed to learn, was the character of the God who had chosen him.

The Message is in the Medium

I am not that kind of god

At the point of sacrificing his son God commanded Abraham to stop, he provided a ram and Isaac was saved. In essence, God said, “I am not that kind of god. I am not like the common gods that you see around you that hurt and destroy and damage. I am not a god who destroys life, but one who gives life. I am the redeemer. I am the provider.”

This passage is one of the major turning points in understanding God in the whole history of humanity. It is a watershed lesson about the character of God. This is the beginning of the comprehension that God is a God of love, provision and redemption. That understanding begins here and grows throughout the Bible, culminating in the cross of Christ. Isaac’s sacrifice is the prelude to the cross, in which God says to humanity, “Not only do I not bring death and destruction, but I suffer death and destruction so that you may have life.” In that greatest of all accommodations to our weakness – the cross – lies our salvation. God becomes a frail human being dying on a cross, bringing life to all, showing us that the greatest God is the one who has the greatest love.

When this passage is looked at through our modern cultural lenses, it is easy to fear that God may be a god of terrors and an arbitrary despot. But this is not the intended lesson. Rather, it was understood by Moses, the Israelites and all the worshippers of God throughout scripture, as a foundational lesson revealing the sacredness of human life and God’s redemptive nature. Abraham had a lesson to learn and through him, humanity had a lesson to learn about the true character of the God who provides.

God is light; in him there is no darkness at all

Would I kill my child if God told me to? Absolutely not. Because that is not the God I worship. We know and believe that God will never do nor command that which is evil because of Jesus Christ. “This is the message we have heard from him and declare to you: God is light; in him there is no darkness at all” (1 John 1:5 TNIV).

If you would like to contact Mark, please use the Contact Me form. If you would like to leave a comment, please use the “comment” link at the bottom of this article.

Mark,

Thank you. As always, insightful, provocative and fuel for the fire. I’m currently studying the life of Hezekiah and I am finding that our culture is so far removed (the animal sacrifices, the fertility gods…) that each piece needs careful attention and explanation. I am finding it facinating, however, to find parellels to our own situation once the ground has been dug.

Thanks for your encouraging response, Tim. As with the Abraham and Isaac story, our cultural presuppositions often cause us to ask the wrong questions, questions that would never have occurred to the original audience. Careful consideration of the original context, as you are obviously doing, is important so that we can approach the text with the right set of “lenses.”

Great article, Mark. It’s very helpful and affirming. I’m in the middle of sermon prep for Sunday and discussing the same cultural filters from the ancient Near East in relation to the creation account. Thanks again for getting my gray matter working.

Thank you Mark. Very interesting. A question that I have been asked, however, is “What kind of a God would order people to kill every man, woman and child of a nation-city?” Because He didn’t stop that. I’ve heard, and thought of, varied responses, such as: “We don’t see sin as seriously as God does”, and “These city-nations were so far gone that there was just nothing else to do with them,” and “since the adults had to be killed it would have been cruel to leave the children alive” – and all of these answers fall short of anything that would satisfy most modern thinkers, myself included. My only answer (to myself) is: “I just don’t understand, but I trust God”.

Thanks John,

I appreciate you “raising the bar” by providing those questions to which I also do not have a satisfactory answer. Nonetheless, what I would hope is that this article would show that if this story, which has been also criticized by those with a modern perspective, can be understood when seen through a more culturally sensitive grid, then perhaps there are cultural dynamics going on in these other stories that we need to understand in order to judge the situation appropriately.

The second point that I would make is that we are called upon, as Christians, to view the OT through the cross and resurrection of Christ. The God of the OT must be consistent with the greater revelation of his mercy and grace found in Jesus. This doesn’t answer the question, but it does provide the foundation for the statement of faith you mentioned: “I trust God.”