My experience as a Bible translator living cross-culturally, along with completing a missiology DTh in intercultural studies, has given me an understanding of how language and culture affect communication. I have come to believe that the dynamics of human interpretation—both its power and its limitations—point us toward a hermeneutical lens that can guide our faithful interpretation of God’s communication in Scripture.

Some material in these articles has been taken from my Intercultural Theology course given as an instructional lecture series with Northwest Baptist Seminary. That course provides a more extensive examination of some concepts introduced here.

I know I have blindspots; the trouble is I can’t see where they are. My desire is not to be right, but to pursue truth and so I am open to correction. All readers are invited to respond and challenge what I have written. I will be grateful for your insights and for continuing the conversation.

The occasion for this reflection is the dispute over women in church leadership—a disagreement that may lead to division within our Canadian Fellowship of churches. My aim is to propose a biblically faithful way of reading Scripture that allows for the affirmation of women in leadership. I hope to show that this position does not arise from cultural compromise, disobedience, or a rejection of Scripture. While it may not change convictions about male-only leadership, I pray that it will encourage a gracious recognition that this view is rooted in a high regard for Scripture, a desire to glorify Jesus, and a passion for God’s kingdom. Therefore, rather than separation, I pray for a response marked by grace and continued mutually beneficial partnership.

Recognizing the many influences that shape how we read and obey the Bible can make us more aware of our limitations, lead us to interpret with greater care and skill, foster a humble posture of ongoing dialogue, and help preserve our unity.

There are seven articles that develop the hermeneutic as follows:

- Reading the Bible as revelation: An introduction to the hermeneutic

- Rather than reading the Bible as a manual of commands to obey, the Bible is a revelation of God’s will, character and mission to which we conform

- Obedience as conformity to the heart of God

- Obedience is about children striving to be like their father rather than servants following rules

- Why we ask “why:” The Limits of Culture and Language

- Recognizing the limitation of our cultural location gives us pause so that we do not take illegitimate shortcuts in our understanding.

- A Framework to guide the Process of Interpretation

- Useful responses to help navigate cultural limitations and lead us to a more robust interpretation of Scripture.

- Developing theology through the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation

- Since we generate our interpretation through a theological grid and within a cultural context, the development of theology needs to be done with care.

- Biblical support for the proposed hermeneutic

- Discovering Jesus’ and the apostles’ hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation.

- Addressing disputed verses on women in leadership through the hermeneutical lens

- Examining verses that are used to forbid women from ecclesial leadership through the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation.

NOTE: Chatgpt was used for editing, but not generative purposes

Part 1: Reading the Bible as Revelation: An introduction to the hermeneutic

Hermeneutics “is the science and art of interpreting the Bible.”[1] It involves discerning how we move from the biblical text to theological understanding taking into account the complexity of that process. Hermeneutics can be described as reading Scripture in community for the purpose of bringing our beliefs, commitments and behaviors into alignment with God’s revealed purposes. This work is complex because of the historical, geographical, linguistic, and cultural distance between the world of the biblical authors and audiences and the contexts of modern readers.

The hermeneutic proposed in this series of articles arises from the process of theological development that naturally takes place among believers in their contexts: Readers engage with the text through the assumptions, questions, and priorities they bring to it, and they shape their theological understanding according to the perceived relevance of the message within their setting. When they are committed to being faithful to the intention of the divine Author, the Holy Spirit guides them to understand and embody the will, character, and mission of Jesus.

The hermeneutic I will propose is grounded in the understanding that we are not called to obey and follow the Bible; instead, the Bible calls us to obey and follow Jesus. For those who struggle with discerning the difference, consider the Pharisees who diligently studied the OT scriptures. They had obedience to God—known as the tradition of the ancestors (Mt 15)—down to a science, but in their attempts to obey God’s commands, they missed (and dismissed) the incarnate Word.

Jesus claimed he brought “new wine” that disrupted those traditions (Mt 9:17; Mk 2:22; Lu 5:37-39). He challenged the religious teachers to re-evaluate their understanding through the lens of who he was, the nature of his kingdom, and what it would mean to follow and obey him. Jesus declared to the Pharisees in Matthew 12 that “something greater” than the temple, the law and the insight of Solomon was present, something that not only overthrew nationalistic visions, legal foundations and established wisdom, but also established a kingdom-centered way to engage life beyond conformity to commands—a kingdom with a person, Jesus, on the throne, who rules by his Spirit.

The implications of these passages for this hermeneutic will be explored in a later article, but these comments establish at least one reason to clarify how we are to discern God’s will from our reading of Scripture: we are not responsible to maintain the theology of godly leaders of the past, no matter how much we respect them. Instead, we are called to test the spirits, the theologies, and the narratives that surround us according to Jesus’ “new wine.” A hermeneutic that does justice to Jesus’ new wine should help us address conflicting theologies of gender, theologies of hierarchy, and theologies of human authority in the kingdom God.

Summary Description of the Hermeneutic

The following is a summary of the “hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation,” or the “contextually sensitive hermeneutic,”[2] which will be referred to throughout the articles:

We are called to read Scripture as God’s self-revelation, given through prophets and apostles within their historical and cultural settings. By discerning God’s will, character, and mission in each passage, we focus on the divine Author, engage a broad theological framework and acknowledge the differences between the biblical context and our own. This keeps us from assuming that culturally shaped instructions or practices in Scripture must be reproduced today. Instead, we pursue obedience by conforming our lives to God’s revealed character and purposes. God’s people express obedience in ways that (1) navigate cultural differences, (2) remain consistent with what we have discerned about God from Scripture, and (3) embody God’s mission within the local body of Christ through contextually meaningful behaviors.

This hermeneutic addresses the following challenges to interpretation that will be explored in these articles:

- We always interpret from a theological perspective—a human construct developed over time through exposure to God’s revelation and other influences.

- We always interpret from an enculturated position, using the language and concepts granted to us from our context.

- Communication is complex and requires dialogue within community in order to move to appropriate action and application.

- As fallen humans, we are limited and susceptible to misunderstanding and inconsistency. Humility before God and openness to correction is required.

- A biblical understanding of concepts such as authority and the implications of gender should not be assumed when reading a verse. Instead, we need to recognize the influences and assumptions that shape our theology (faith) and then test them.

- We cannot assume that even a “clear” verse is properly understood. Because of the historical and conceptual distance between us and the original author/audience, there are contextual dilemmas and tensions that are not immediately obvious.

- Obedience is not about following rules and emulating biblical patterns, but conforming to God’s revealed will, character and mission.

- Conforming to God’s revealed will, character and mission requires expressions that are contextually meaningful.

- We are constantly engaging in a dialogical process between theology (faith), text (Scripture) and context (the influences that shape our thinking and understanding of reality). This liminal reality is our human condition and it encourages us not to establish practices based on a few verses but on a robust theology that reveals God’s deeper purposes. Only then can we confidently apply our conclusions to ecclesial contexts today.

This hermeneutic welcomes dialogue with others—across history, within our own culture, and interculturally—to confirm that our interpretation aligns with Scripture and that our application genuinely reflects the message we aim to live out.

It also implies that it is not appropriate to take any narrative, command or promise in the Bible and apply it directly to our situation today. Nor is it possible to extract a “kernel” of truth or a timeless principle that can be understood apart from a cultural context or that can be applied universally. All communication is culturally embedded.

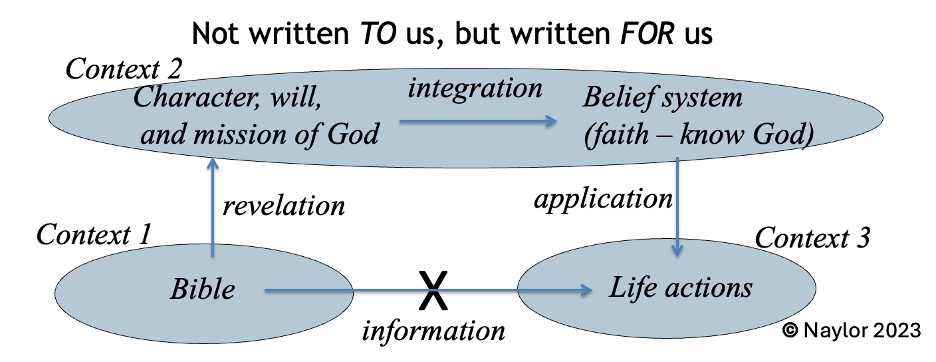

The following Contextually Sensitive Hermeneutic diagram illustrates the process:

The bottom (information) arrow with the “X” shows that we should not read the Bible as if its teachings move directly from the text to our situation without interpretation. We cannot simply take biblical instructions and apply them straight to our context because we are dealing with two different cultural contexts—the biblical culture and our own. A direct, culture-to-culture transfer is impossible because of assumptions, priorities, and questions that shape our beliefs.

Instead, we approach Scripture as God’s self-revelation—his nature, will, and mission—communicated in a time, place, and cultural setting different from our own (left arrow—revelation). From that revelation, we develop a theological understanding of who God is and what he desires (top arrow—integration). Only then can we express our obedience in culturally appropriate actions today (right arrow—application).

In summary: The meaning of any passage reveals God’s intention within a particular context distinct from our own. Discerning God’s will, character, and mission from that intention calls us to trust in him and to shape our lives in conformity with his purposes—grounded in our relationship with God in Christ, rather than by mere adherence to instructions or commands found in the passage[3].

Examples of how the hermeneutic is used

It may be helpful at this stage to point out how the discovery method of disciple making uses this hermeneutic to engage God’s word in order to develop theology. In disciple making the goal is not to pass on a theological system or doctrinal statements, but to assist believers in their discovery of who God is, what he wants, and what he is doing in this world. Group participants learn to read the Bible as revelation. Thus, key questions for any passage are, “How does this message show us God’s will, God’s character and God’s mission?” Once agreement is reached on what God is like, what he wants and what he is accomplishing, participants are challenged to conform their life to that vision[4].

A personal motivation for promoting this hermeneutic arises from my experience ministering among orthodox Muslims in Pakistan whose religious orientation parallels that of the Pharisees. When our focus is on submitting to Scripture as the primary way of following Jesus, we risk adopting an Islamic understanding of obedience—submission to Allah by conforming to traditions and laws. We evangelicals distort our theology when we treat Scripture as a collection of commands to obey rather than as a revelation of God our Father to whom we conform our lives.

Without doubt, the Bible has been given to us as a guide into obedience, but how that process should be worked out is the question.

No text is directly applicable to us or our context today, no matter how “plain” the meaning may appear. Scripture is written for us (2 Tim 3:16 NIV: “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness”) but it is not written to us, because we are not the original audience being addressed.

What does it mean for the Bible to be given “for us” but not “to us”? The point of the Bible is not primarily to help us live a moral life pleasing to God but to bring us into relationship with God through Christ (Jn 3:16; 20:31). We come alive “in the Spirit” so that we can live out our adoption as children (Rom 8). Our ultimate aspiration is not to be obedient servants but children whose lives are conformed to the image of Christ.

Obedience that is not rooted in the outworking of the gospel drifts toward the legalism of the Pharisees. In orthodox Islam, the true believer is the one who submits to Allah’s will—a noble aim as far as it goes, evoking the image of a servant awaiting the master’s command. When the master is God, such devotion is honorable. But this is not the orientation of a follower of Jesus. We are called to embody the vision of the kingdom which goes beyond keeping commands to sharing the heart and desires of the One who gives them. Our task is to discern the purposes of Jesus in each situation and respond out of love for the King, desiring what he desires. Jesus loved the Rich Young Ruler not because he had kept the commands from his youth, but because he hungered for the kingdom in a way that reached beyond the commands.

We are called to live under a new covenant of grace—not to bind ourselves to commands, however clear they may appear. Consider children being told, “Do not touch the stove!” This is a clear command, and obedience means staying away from danger by literally not touching the stove. But maturity means learning to touch the stove properly; understanding both the command and the purpose behind it allows the command to be obeyed by appropriately touching the stove.

This conviction is parallel to the theological realization that Jesus did not come primarily to save us from guilt, shame and fear. Those conditions are the result of sin—rebellion against God—and therefore, they are appropriate consequences. Rather, by saving us from sin (Mt 1:21; Jn 1:29; 2 Tim 1:15; 1 Jn 3:5) and bringing us into a right relationship with God, Jesus simultaneously frees us from guilt, shame and fear. Our focus, then, is not on the secondary symptoms but on the primary issue—rebellion from which we must repent. To be saved from sin is to be redeemed into a right relationship with God (Rom 3:21-26[5]) with a desire is to live “in Christ.”

Similarly, but with a profound hermeneutical rather than theological reorientation, our primary use of Scripture is not to find commands to obey—that would be focusing on secondary concerns. We first discover and then conform ourselves to God’s will, character and mission as good children who want what their father desires for them. This does not lead to disobedience but to conforming to the “new wine” of kingdom living expressed in ways fitting for our context. For the believer, it is the only way to be truly obedient.

The pathway from text to application

The pathway from the biblical text to its appropriate application is not straightforward or simple and there is potential for error—even for those who desire to follow God’s will. It is possible even for dedicated biblical scholars to misinterpret or misapply God’s word, missing God’s intent for a specific time and place. The Pharisees in the time of Jesus are an obvious example of this danger. Nevertheless, by remaining aware of interpretive pitfalls and by following the hermeneutical patterns and priorities evident in Jesus’ own ministry—reflected and reiterated throughout the New Testament—we can live out biblically informed expressions of our faith.

At the same time, it would be unwise to ignore the wealth of understanding and insight provided by godly scholars throughout the centuries who have guided the church in how to live out the Christian life in a worshipful and impacting manner. What is required is to refresh our theology in each new setting and generation by revisiting the authoritative text (the Bible). This allows us to benefit from and critique the wisdom and traditions of our past by giving priority to how Jesus dealt with Scripture and the issues of his day.

This wrestling between traditional theologies and Scripture does not happen in a vacuum. We struggle to be “in the world, but not of the world” (John 17:14-16) and every generation and culture is faced with narratives that clash with kingdom values. Like the churches of Pergamum and Thyatira (Rev 20:14-15, 20), we can be tempted towards compromise. How can we find expressions of our faith that both resonate authentically with our context and uncompromisingly reflect the light of Jesus and what is true to God’s will, character and mission?

As an example of how our interpretive process can go wrong, one of my students reported that in Africa some tribes “are Christian, but still practice polygamy and believe it is biblical. These tribes argue their case by stating that the fathers of our faith (Abraham, Jacob, David, etc.) practiced polygamy, showing that it is a cultural matter—not a sin issue.”[6]

I view this interpretation as poor contextualization based on an inappropriate hermeneutic. It reveals a legalistic approach to Scripture (i.e., look for biblical examples to follow, commands to obey, or promises to claim by using the Bible as a “manual”), rather than developing theologies of marriage and gender by discovering the will, character and mission of God. Developing our theology through the lens of how Jesus revealed the Father is key for Scripture interpretation and prevents us from building theological frameworks and practices based on select biblical practices and commands.

In the following articles, I will seek to demonstrate the necessity of this less direct approach to interpreting Scripture, explain how this hermeneutic guides us toward appropriate application, show how it is employed within Scripture itself, and finally use it to examine passages often cited to restrict women’s roles in ecclesial leadership. Because the controversy prompting this reflection arises from a shared desire to obey God, the next article will explore what it means to be obedient to God’s Word.

Footnotes:

[1] Donald K. Campbell, “Foreword,” in Basic Bible Interpretation: A Practical Guide to Discovering Biblical Truth, ed. Craig Bubeck Sr. (Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook, 1991), 19.

[2] Both of these descriptions are used in these articles. “Hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation” focuses on how the Bible is to be read, while “Contextually Sensitive Hermeneutic” emphasizes the intimate connection between meaning and context.

[3] Scholars will recognize this approach as a version of theological hermeneutics. “When we speak of theological exegesis, particularly when we acknowledge the Spirit’s role… we are speaking … of the way that God, working through the text, is reshaping us.” from Richard B. Hays, “Reading the Bible with Eyes of Faith: The Practice of Theological Exegesis,” ed. Joel B. Green, Journal of Theological Interpretation, Volume 1, no. 1–2 (2007): 15.

[4] This approach affirms the sufficiency of Scripture as the curriculum, the Holy Spirit as the teacher, and the dynamic of the community for challenge and correction. This foundational engagement of believers with God’s revelation does not negate or neglect God’s blessing in the church of those with apostolic (missions), prophetic (proclamation), evangelistic (gospel message), shepherding (pastoral), and teaching (training in righteousness) callings (APEST, see Eph 4:11).

[5] “If then sin as unrighteous activity means activity that ruptures our relationship with God, righteousness or being ‘made righteous’ means to have the effects of sin nullified by entering into a restored relationship with God” (Achtemeier, P. J. (1985). Romans (p. 63). Atlanta, GA: John Knox Press).

[6] J. Claybaugh, CICA: Transforming Discipleship session 2, Fall 2025. Used with permission.

About twenty years ago, while attending seminary in Southern California, I had the opportunity to minister in the Pasadena area and to become familiar with the theological and missiological trajectory associated with Fuller’s School of Theology. During that time, one reality became increasingly clear: theological drift in the church often enters NOT through open rejection of Scripture, but through well-intentioned attempts to reinterpret biblical authority in the name of mission, cultural sensitivity, or experiential pragmatism. When Scripture’s function is subtly redefined rather than openly denied, the resulting theology often sounds faithful while quietly reshaping the church’s understanding of obedience, authority, and truth.

I’d like to offer the following critique with that concern in mind. The central problem with the hermeneutic proposed in this article is not its stated desire to follow Jesus, nor its expressed concern for humility, dialogue, or cultural awareness. Those aims, rightly understood, are commendable. The problem lies in a false dichotomy that the article repeatedly assumes and builds upon: that obedience to Scripture can be meaningfully distinguished from obedience to Christ.

This division is defended by appealing to Jesus’ confrontations with the Pharisees, suggesting that their error lay in faithfully obeying biblical commands rather than in following the living Word himself. That claim is not only exegetically indefensible; it reverses the very logic of Jesus’ rebukes and functions as the theological hinge upon which the entire hermeneutical framework turns.

If the portrayal of the Pharisees is mistaken, and I will argue that it is, then the foundation of the proposed hermeneutic is compromised at its core. Jesus did not oppose Scripture in the name of kingdom obedience, nor did he rebuke the Pharisees for submitting too carefully to God’s revealed Word. Rather, he condemned them for disobeying Scripture through the elevation of human tradition, for misreading the very texts they claimed to uphold, and for refusing to follow the clear testimony of those Scriptures concerning him. It is therefore necessary to examine whether the article’s appeal to the Pharisees represents Jesus’ actual teaching, or whether it functions rhetorically to justify a reconfiguration of biblical authority under the banner of Christ-centered interpretation.

The proposed hermeneutic rests heavily on a familiar contrast: the Pharisees represent obedience to Scripture reduced to rule-keeping, while Jesus represents a relational, kingdom-centered obedience that transcends commands. According to this framing, the Pharisees “had obedience to God… down to a science,” yet in doing so “missed (and dismissed) the incarnate Word.” This contrast is rhetorically powerful—but biblically and historically mistaken.

Truth: Jesus did not rebuke the Pharisees for obeying Scripture too carefully. He rebuked them for disobeying Scripture while claiming to uphold it. The article appeals explicitly to Matthew 15, yet Matthew 15 directly contradicts its claim. Jesus’ charge against the Pharisees is unambiguous:

“Why do you break the commandment of God for the sake of your tradition?” (Matt 15:3)

“For the sake of your tradition you have made void the word of God.” (Matt 15:6)

The issue is not excessive submission to Scripture, but the elevation of human tradition over divine command. Jesus is not warning against taking Scripture too seriously; he is condemning those who refuse to submit to it honestly. To cite Matthew 15 as evidence that obedience to God’s commands leads one away from Christ is to reverse the text’s meaning entirely.

Truth: Jesus’ method was exegetical, not anti-textual. Throughout the Gospels, Jesus repeatedly confronts the Pharisees with the question, “Have you not read?” His disputes are not rejections of Scripture, but arguments over its proper interpretation.

Jesus appeals to Moses, the prophets, and the Psalms; he reasons from Scripture, corrects distortions of Scripture, and exposes selective readings that protect power and prestige. Even when Jesus declares that “something greater than the temple” is present (Matt 12), he does not relativize Scripture; he interprets it. HIS AUTHORITY DOES NOT STAND OVER AGAINST THE WRITTEN WORD; it reveals its true intent. Jesus never contrasts “following me” with obeying God’s Word. He insists that Scripture, rightly understood, bears witness to him.

Matthew 23 is particularly decisive. Jesus says: “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat, so do and observe whatever they tell you, but not the works they do.” (Matt 23:2–3). Jesus affirms the legitimacy of their teaching authority insofar as it reflects Moses. Their failure is not command-based obedience, but hypocritical disobedience—saying one thing and doing another.

Most strikingly, Jesus adds: “These you ought to have done, without neglecting the others.” (Matt 23:23). This statement alone dismantles the article’s implied opposition between obedience and kingdom faithfulness. Jesus affirms obedience to God’s commands while condemning selective, self-serving obedience divorced from justice, mercy, and faithfulness.

The hermeneutic under review depends on separating obedience to Scripture from obedience to Christ. Scripture itself never makes this move. Jesus affirms that “Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35), insists that his followers live by “every word that comes from the mouth of God” (Matt 4:4), and teaches that love for him is expressed through obedience to his commands (John 14:15). The apostles likewise ground obedience to Christ in obedience to their written instruction, received as authoritative teaching from the Lord.

To oppose the incarnate Word to the inscripturated Word is not Christ-centered interpretation; it is a functional redefinition of authority that relocates obedience from divine revelation to theological inference.

Why does this matter? This misreading of the Pharisees is not incidental; it performs essential work for the hermeneutic being proposed. Once obedience to clear biblical instruction can be labeled “Pharisaical,” resistance to theological revision is reframed as spiritual blindness rather than interpretive disagreement. Those who submit to apostolic teaching are subtly cast as legalists, while those who revise that instruction are presented as faithfully embracing Jesus’ “new wine.”

Jesus never used the Pharisees to warn against obedience to Scripture. He used them to warn against disobedience disguised as faithfulness. A hermeneutic built on the opposite conclusion cannot sustain the weight the article places upon it.

The issue raised by this article is therefore not a difference in tone, emphasis, or pastoral instinct, but a fundamental question of authority. A hermeneutic that pits obedience to Scripture against obedience to Christ, that is justified by a misreading of Jesus’ confrontation with the Pharisees, cannot provide a stable or faithful framework for theological discernment. Jesus did not free his followers from submission to God’s Word; he called them into deeper submission to it by revealing its true meaning and purpose. Any interpretive approach that relocates authority from the text of Scripture to the theological judgments of the interpreter, however well intentioned, ultimately undermines the very Christ it claims to honour.

Dear BK Smith

Thank you for taking the time and effort to respond to the article. I hope you will continue reading the remaining pieces in the series, as I believe many of the concerns you raise are addressed there. This first article serves as an introduction to the hermeneutical framework, while the subsequent articles develop the argument in greater detail and should provide further clarity.

That said, I would like to address several key misunderstandings in your response that may help orient you more clearly to the argument I am making.

Perhaps the most helpful place to begin is your concluding comment: “Any interpretive approach that relocates authority from the text of Scripture to the theological judgments of the interpreter, however well intentioned, ultimately undermines the very Christ it claims to honour.” This concern reflects precisely the categorical issue that prompted me to address the question of women in ecclesial leadership from a hermeneutical perspective. If there is clarity at this level, then careful and constructive exegesis becomes possible.

The issue is not that authority shifts away from Scripture. Rather, authority always remains in Scripture, but access to that authoritative message is necessarily mediated through human interpretation. Hermeneutics matters because it acknowledges our finite and situated access to truth. All knowing is perspectival, and to deny this is ultimately self-deceptive. When some claim to ground their position in the “authority of Scripture,” while attributing differing views to “theological judgments of the interpreter,” they fail to recognize that their own engagement with Scripture is also shaped by interpretation. I address this issue more fully in parts three through five of the series. Recognizing our God-ordained limitations enables us to approach Scripture with humility and to learn how to interpret it more faithfully.

By way of illustration, I once had a disagreement with a pastor over a verse in one of Paul’s epistles. The substance of the disagreement is not important here, but his comment was revealing. He said, “You are not arguing against me; you are arguing against the apostle Paul.” I responded by clarifying that it was not a matter of him standing beside Paul while arguing with me, but rather that we were standing together, both seeking to understand Paul. All engagement with Scripture is an act of interpretation, and no one has privileged or unmediated access to the text.

A similar issue appears in your statement: “Once obedience to clear biblical instruction can be labeled ‘Pharisaical,’ resistance to theological revision is reframed as spiritual blindness rather than interpretive disagreement.” The phrase “obedience to clear biblical instruction” is precisely what requires careful examination. What constitutes genuine obedience, and what makes a command “clear”? If obedience turns out to be conformity to a misinterpretation, or if clarity reflects unexamined cultural assumptions rather than Jesus’ intent, then a serious problem emerges. It is at the level of hermeneutics that we learn how to approach Scripture in a way that is both faithful and fruitful, which is the central concern of these articles.

I would also like to clarify a misunderstanding regarding my statement that “we are not called to obey and follow the Bible; instead, the Bible calls us to obey and follow Jesus.” You interpreted this as suggesting a tension or opposition between Scripture and Christ. As a result, much of your response argues that obedience to Scripture should be equivalent to obedience to Christ—a position with which I fully agree and which the articles themselves affirm. There is no “implied opposition between obedience and kingdom faithfulness” in what I have written.

Rather, my point is to underscore the primary purpose of Scripture: to draw us into a living relationship with Christ. The Bible should not be approached primarily as a rulebook, but as a witness that points us to Jesus. This is a theme developed throughout the series. It is possible to “obey” biblical commands in ways that, because of misinterpretation, actually move people away from the heart and intent of Jesus. For example, the Pharisee’s complaint about Jesus’ healing on the Sabbath, or those who today insist on Saturday as the true Sabbath that includes OT restrictions. When divine authority is claimed for particular interpretations and applications that fail to reflect kingdom values, such as the argument for polygamy given in the article, a hermeneutical problem is revealed—one that these articles seek to address.

I would also like to point out that the “human tradition” Jesus critiqued among the Pharisees was, in fact, a significant part of the interpretive lens through which they read Scripture. Jesus identified this interpretive tradition as “human” because it often distorted the meaning and purpose of God’s revelation, leading to hypocrisy and a misplaced focus on what God truly desired. Because their hearts were not rightly oriented toward God, their reading of Scripture was also distorted. Jesus’ rebuke was, at least in part, an effort to reorient them toward a faithful interpretation of the very Scriptures they claimed to uphold.

I trust that the remaining articles will provide further clarification on these points and contribute to a constructive and shared engagement.

This is so timely and clear. Well done, thank you for taking the time to write this.

Thanks Wes, I appreciate the encouragement! I just posted part 4.