NOTE: Mark is available to work with our FEBBC/Y churches to coach missions committees in their role in leading their local church in the area of missions. Please contact Mark via the Contact Me form or view Mark’s Coaching page

A balanced diet, a balanced economic portfolio, a balanced lifestyle – we are constantly challenged to keep many things in our lives in balance, for the sake of health and sanity! What about doing missions in the local church? There are so many options today to be involved in cross-cultural, evangelistic and compassionate ministries – not to mention the demand for missions dollars from hundreds of worthy causes – that missions committees or global missions teams have to make difficult decisions concerning the limit and range of their church’s participation.

A balanced diet, a balanced economic portfolio, a balanced lifestyle – we are constantly challenged to keep many things in our lives in balance, for the sake of health and sanity! What about doing missions in the local church? There are so many options today to be involved in cross-cultural, evangelistic and compassionate ministries – not to mention the demand for missions dollars from hundreds of worthy causes – that missions committees or global missions teams have to make difficult decisions concerning the limit and range of their church’s participation.

For a variety of reasons, some mentioned in a previous article, the scope of “missions” in our churches today has broadened far beyond the traditional understanding. While affirming the missional thrust of churches who strive to be involved in God’s mission both locally and globally, I would also like to challenge churches to not neglect the task that has defined missions through the centuries: taking the gospel to those who have not heard. In this article, evidence for this focus in the modern missions movement (from Wm. Carey through to the present) is presented along with the concept of the “Acts 1:8 portfolio,” which is a helpful structure for churches to assist them in fulfilling the mandate God has given to participate in his mission.

The Modern Missions Movement: to the unreached

The desire to take the gospel to those who have not heard and who have no access to the gospel except through the initiative of an outsider reflects the apostle Paul’s description of his ministry concern in Rom 15:19-21.1 This perspective has been a defining characteristic of the modern missions movement and played an important role in setting priorities for missionaries and missions agencies.

The desire to take the gospel to those who have not heard and who have no access to the gospel except through the initiative of an outsider reflects the apostle Paul’s description of his ministry concern in Rom 15:19-21.1 This perspective has been a defining characteristic of the modern missions movement and played an important role in setting priorities for missionaries and missions agencies.

Ralph Winters helpfully divides the modern missions movement into three eras: The first era (1792-1910) he entitles “To the Coastlands”. Initiated to a large extent by the efforts of Wm. Carey, this was the beginning of mission societies who sent missionaries to lands where the gospel was unknown. The second era (1856-1980) was characterized by a movement inland to “the unoccupied fields,” again reflecting the desire to contact those who had no previous exposure to the gospel. The third era (1934-present), which Winters calls “To the Unreached Peoples,” is characterized by an increasing sensitivity to those barriers to the gospel beyond geography and the focus on people groups with distinct ethnic identities. These groups require an outside source in order to be exposed to the gospel message.2

10,000 people groups = “final frontier of missions”

Even though the unreached have been the primary focus of traditional missions, this should not be confused with the comprehensive missional responsibility of the church. At the beginning of the modern missions movement the unreached lived in the majority of the world, the concern for them in the western protestant churches was relatively small and, due to the lack of a missions effort, there were few successes in cross-cultural ministry that needed strengthening. However, because of God’s gracious actions and the sacrifice of missionaries through the past few centuries, this is no longer true. Now, with the shift of Christianity to the south and east, it is estimated that there are only 10,000 people groups remaining that are unreached.3 This has been called the “final frontier of missions” and while “there is a great need for thousands of new missionaries to reach them,”4 the vast percentage of people in the world now live within “reached” contexts. It is the 10,000 people groups that are identified as the concern of traditional missions in order to complete the mandate in accordance with the spirit of the apostle Paul’s ministry and his desire “not to build on another’s foundation.” In this understanding of missions, the end of the task is in sight, the course has been mapped. For example, Wycliffe has initiated Vision 2025 which states, “By 2025, together with partners worldwide, we envision Bible translation in progress for every language that needs it”5 – a key component towards the completion of the traditional missions mandate to reach the unreached.

Traditional Missions as one part of the Missional task of the church

But while the end of traditional missions can be postulated, it is not the only missional responsibility of the church. The apostle Paul consistently completed his task of establishing a group of believers and then moved on, even when the vast majority of people in that area were unsaved. Why? Because with the establishment of a church, an internal witness to carry on the gospel mandate had come into existence. Following this pattern, traditional missions is understood as the initiative of the church on the outside crossing boundaries to those inside a people group. But when that initiative bears fruit, God’s mission6 has only just begun, for then the missional responsibility shifts to the church on the inside of the people group. In fact, the larger missional task facing the church today is the growth of the kingdom among those people groups who do have a gospel witness, not to mention the needed re-establishment of the gospel in places where people have turned away from their parent’s faith. Churches and mission agencies rightly consider these tasks as part of their missional responsibility, even though they move beyond the traditional focus of missions.

But while the end of traditional missions can be postulated, it is not the only missional responsibility of the church. The apostle Paul consistently completed his task of establishing a group of believers and then moved on, even when the vast majority of people in that area were unsaved. Why? Because with the establishment of a church, an internal witness to carry on the gospel mandate had come into existence. Following this pattern, traditional missions is understood as the initiative of the church on the outside crossing boundaries to those inside a people group. But when that initiative bears fruit, God’s mission6 has only just begun, for then the missional responsibility shifts to the church on the inside of the people group. In fact, the larger missional task facing the church today is the growth of the kingdom among those people groups who do have a gospel witness, not to mention the needed re-establishment of the gospel in places where people have turned away from their parent’s faith. Churches and mission agencies rightly consider these tasks as part of their missional responsibility, even though they move beyond the traditional focus of missions.

This distinction between … missions … and the broader missional task … is not one of importance

This distinction between the narrowly defined traditional task of missions – the church on the outside reaching across ethnic boundaries – and the broader missional task of the newly formed church on the inside, is not one of importance or even of priority when speaking of participating in God’s mission. God’s concern is for the whole world. Influencing others locally or globally for God’s kingdom is equally a part of God’s mission, whether or not it is classified as missions. Affirming the reality that all levels of participation in God’s mission are equally valid and important reflects the spirit of the apostle Paul when he spoke of being called to the Gentiles, while Peter was called to the Jews (Gal. 2:7,8). Separate ministries, both are equally valid and needed, but it is only the former that is traditionally referred to as “missions.”

Assessing your Missional Portfolio

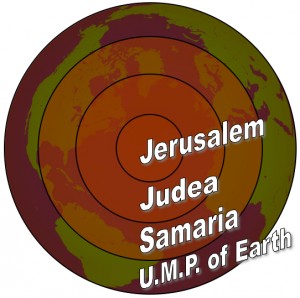

A helpful way to understand these concepts is to use Jesus’ vision of the expanding impact of the gospel in Acts 1:8 as a “portfolio”7 for local church involvement in God’s mission: “you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.” Using this model, the traditional understanding of missions parallels the final element in Acts 1:8, “the ends of the earth,” the pioneer extension of the kingdom to those people who have no access to the gospel.

A helpful way to understand these concepts is to use Jesus’ vision of the expanding impact of the gospel in Acts 1:8 as a “portfolio”7 for local church involvement in God’s mission: “you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.” Using this model, the traditional understanding of missions parallels the final element in Acts 1:8, “the ends of the earth,” the pioneer extension of the kingdom to those people who have no access to the gospel.

“Samaria” can refer to cross-cultural partnerships with established churches who welcome support in needed areas, such as leadership development or ministries of compassion. The people group is “reached” – the believers have taken up their missional task – but the consolidation and expansion of previous missions efforts requires outside involvement. Both “Samaria” and “the ends of the earth” can also be identified by the boundaries that must be crossed in order to participate in God’s mission, including boundaries of culture, language, identity, geography, misinformation, prejudice, values, and worldview, as well as psychological and socio-economic barriers.

“Judea” describes regions and people outside of the immediate influence of the local church, but because of a common identity through shared culture, language and history, the primary boundary is geographical. In order to provide a lasting impact in this area, churches often join forces, e.g., the Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches of Canada (FEBCC), to cooperate in joint ministries such as planting churches.

“Jerusalem” refers to the local missional task of an established church. It includes all the ministries, individually and collectively, that affect the people who come in contact with the members of that church. Even as Paul expected the churches he planted to expand the kingdom where they were, so this is a major responsibility of local church members in their daily relationships.8

The challenge of the Acts 1:8 portfolio approach for churches today is to play a strategic role in each of these four areas. At the same time, it is neither necessary nor helpful to closely define the borders between these four areas of concern. The borders will be fuzzy and porous, and some ministries may span more than one area, making it impossible to precisely categorize them. The key is to be involved in what God is doing in the world, while recognizing that God’s mission encompasses the whole world. What is needed is a comprehensive missional agenda with a diversified portfolio, so that each church can participate in God’s mission close to home while not neglecting traditional missions: Jesus’ vision for the ends of the earth.

needed is a comprehensive missional agenda with a diversified portfolio, so that each church can participate in God’s mission close to home while not neglecting traditional missions: Jesus’ vision for the ends of the earth.

Unlike today’s economic portfolios, your missional portfolio is guaranteed to produce eternal dividends!

Mark spends part of his time coaching churches for effective involvement in missions. If you are interested in taking advantage of this, please contact him via the Contact Me form. If you would like to leave a comment, please use the “comment” link at the bottom of this article.

- ____________________

- 1 For further explanation of how the apostle Paul’s ministry relates to missions see the article, “If every activity is “missions,” how do we set priorities?“

- 2 Winters, Ralph. 1981. Four Men, Three Eras, Two Transitions: Modern Missions in Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: 253-261. see especially the chart on p. 259.

- 3 A 2006 update from Jason Mandryk of Operation world divides the unreached people groups as follows: Muslim 4100, Hindu 2700, Tribal 2000, Buddhist 1000, Others 600. See “State of the Gospel” download at http://www.operationworld.org/index.html

- 4 Wilson, Nate. Motivations for Missions in http://www.globaltribesoutreach.org/articles.php?id=7. Accessed Dec 21, 2008.

- 5 http://www.wycliffe.ca/aboutus/vision2025.html. Accessed Dec 21, 2008.

- 6 As defined in “If every activity is “missions,” how do we set priorities?” God’s mission “refers to his gracious acts within history to bring redemption to the world.”

- 7 I was introduced to this helpful terminology from 1615 missions coaching material. See http://www.1615.org/about/

- 8 See Significant Conversations for a helpful way to support believers in this role.

A missional church is a church that recognizes that it is on the margins of society and therefore moves out relevantly into its context.

A missional church is a church that recognizes that it is on the margins of society and therefore moves out relevantly into its context.  Even as the vision of Zion in the Old Testament was of the glory of God drawing the nations to the temple for worship, so this church seeks to be an alternate society whose communal expressions as the body of Christ are so influential that it is natural for people to come and be a part of their experience of the kingdom of God. This phenomenon can be observed in small, traditional rural settings and, arguably, in the case of megachurches.

Even as the vision of Zion in the Old Testament was of the glory of God drawing the nations to the temple for worship, so this church seeks to be an alternate society whose communal expressions as the body of Christ are so influential that it is natural for people to come and be a part of their experience of the kingdom of God. This phenomenon can be observed in small, traditional rural settings and, arguably, in the case of megachurches. The essential distinction between missional and communal oriented churches is the outward, incarnational orientation of the former verses the inward, attractional orientation of the latter. But missional churches also differ from communal oriented churches in the way they are structured. Missional churches will prefer a more centered approach, while communal oriented churches tend to adopt a bounded structure. A church with a bounded approach is concerned about determining who is “in” and who is “out” and thus an evangelistic communal church will provide programs designed to draw outsiders into their community or sphere of influence.

The essential distinction between missional and communal oriented churches is the outward, incarnational orientation of the former verses the inward, attractional orientation of the latter. But missional churches also differ from communal oriented churches in the way they are structured. Missional churches will prefer a more centered approach, while communal oriented churches tend to adopt a bounded structure. A church with a bounded approach is concerned about determining who is “in” and who is “out” and thus an evangelistic communal church will provide programs designed to draw outsiders into their community or sphere of influence. A church with a centered approach seeks to maintain the core value of living as disciples of Christ with little concern about defining who belongs to the organization or developing a sphere of influence controlled by the church. Thus a missional congregation defines its identity as followers of Christ within a non-Christian context where they are seeking to point others to the way of Christ. The goal is not to have people “join a church,” but to develop significant social networks with those who are not disciples of Christ in order to awaken them to the realities of the kingdom of God.

A church with a centered approach seeks to maintain the core value of living as disciples of Christ with little concern about defining who belongs to the organization or developing a sphere of influence controlled by the church. Thus a missional congregation defines its identity as followers of Christ within a non-Christian context where they are seeking to point others to the way of Christ. The goal is not to have people “join a church,” but to develop significant social networks with those who are not disciples of Christ in order to awaken them to the realities of the kingdom of God.

The communal oriented church can be compared to a theater. The goal is to encourage people to come in and be a part of what is happening within the program of the organization. To facilitate this the atmosphere is comfortable and appealing, the programs presented are satisfying, and the hope is that people will want to come back and support the agenda. For a theater the agenda is that people enjoy the movie, for the church the agenda is that people should become committed participants.

The communal oriented church can be compared to a theater. The goal is to encourage people to come in and be a part of what is happening within the program of the organization. To facilitate this the atmosphere is comfortable and appealing, the programs presented are satisfying, and the hope is that people will want to come back and support the agenda. For a theater the agenda is that people enjoy the movie, for the church the agenda is that people should become committed participants. The missional church is more like a computer company whose goal is to bring the product into the homes where people live. Their efforts are focused on making the product relevant and appealing to the needs of the person within their context. For example, my wife, Karen, buys her computers from one local company because it provides excellent support coupled with the technology to design computers to meet their customers’ business needs. Their offices and organization are shaped to fulfill this goal. In a similar fashion the aim of the missional church is to make the gospel relevant to people where they live, rather than seeking to create appealing programs that will draw people in.

The missional church is more like a computer company whose goal is to bring the product into the homes where people live. Their efforts are focused on making the product relevant and appealing to the needs of the person within their context. For example, my wife, Karen, buys her computers from one local company because it provides excellent support coupled with the technology to design computers to meet their customers’ business needs. Their offices and organization are shaped to fulfill this goal. In a similar fashion the aim of the missional church is to make the gospel relevant to people where they live, rather than seeking to create appealing programs that will draw people in. In E. R. McManus provides a powerful river metaphor to illustrate the dynamic way church relates to culture 2. I will take some liberty with the picture by adding fish. The missional church lives dangerously in the rapids with the fish that are struggling to swim upstream, while the communal oriented church scoops up the fish in buckets and puts them

In E. R. McManus provides a powerful river metaphor to illustrate the dynamic way church relates to culture 2. I will take some liberty with the picture by adding fish. The missional church lives dangerously in the rapids with the fish that are struggling to swim upstream, while the communal oriented church scoops up the fish in buckets and puts them  in quiet pools on the shore. Rather than seeking protection and security within institutional walls, the missional church trusts in the endurance and indestructibility of the gospel and lives recklessly within the rushing rapids of the world. Leaders of the communal oriented church standing on the edge recognize the dangers of syncretism and compromise, "Be careful, you are getting too close to the rocks!" The riverbank represents a controlled environment that provides a place of refuge and facilitates security from destructive influences in the world. However, for the missional church, the task of the leader is three-fold: to push believers towards the rapids, equip them to thrive in that environment, and keep them away from the rocks.

in quiet pools on the shore. Rather than seeking protection and security within institutional walls, the missional church trusts in the endurance and indestructibility of the gospel and lives recklessly within the rushing rapids of the world. Leaders of the communal oriented church standing on the edge recognize the dangers of syncretism and compromise, "Be careful, you are getting too close to the rocks!" The riverbank represents a controlled environment that provides a place of refuge and facilitates security from destructive influences in the world. However, for the missional church, the task of the leader is three-fold: to push believers towards the rapids, equip them to thrive in that environment, and keep them away from the rocks.

It provides the power to keep going and support for mechanical problems to ensure that the car will continue to run well.

It provides the power to keep going and support for mechanical problems to ensure that the car will continue to run well.