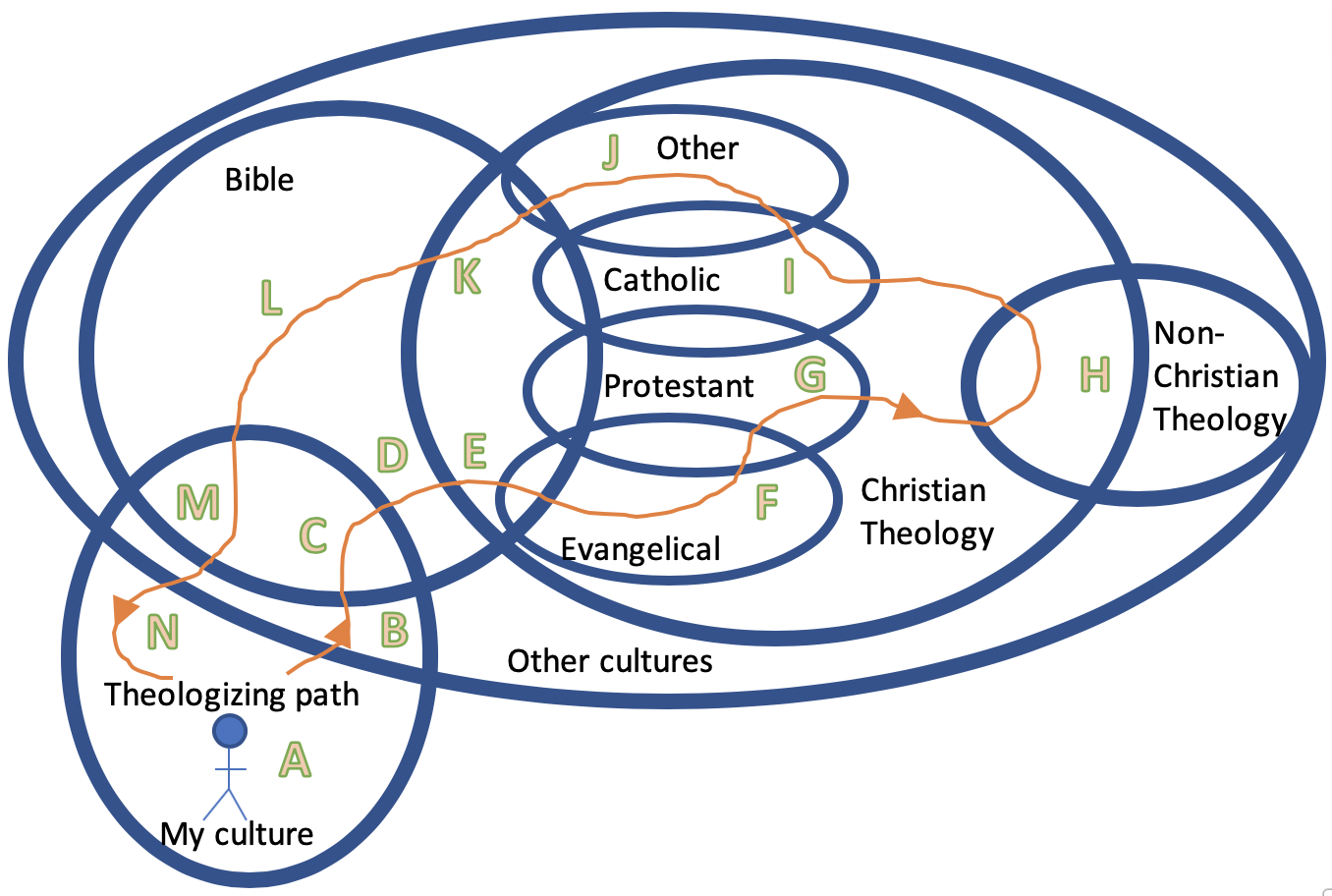

Recognizing the many influences that shape how we read and obey the Bible can make us more aware of our limitations, lead us to interpret with greater care and skill, foster a humble posture of ongoing dialogue, and help preserve our unity. All readers are invited to respond and challenge what I have written. I will be grateful for your insights and for continuing the conversation.

NOTE: Chatgpt was used for editing, but not generative purposes.

Part 7: Addressing disputed verses on women in leadership through the hermeneutical lens

God created men and women to complement one another. Their differences are intended to meet and supplement each other’s needs, producing a unity and synergy that neither sex can fully embody alone. This complementarity is expressed most clearly in marriage, but it is also a vital dimension of life in the body of Christ. The church is meant to display the kingdom of God—an initial answer to the prayer, “your kingdom come on earth as it is in heaven.” Sexual difference, therefore, is a gift from God to be affirmed, protected, and celebrated in families and in the church, with the expectation that God’s kingdom vision—with full validation of that complementarian dimension—will one day be fulfilled throughout the earth.

This biblical vision of male–female complementarity is not disputed within our Fellowship of churches; it is strongly affirmed. What is disputed is how that complementarity should be expressed in ecclesial leadership, and how much diversity between churches should be permitted in the way men and women share responsibility as they work together to fulfill God’s purposes for his kingdom.

Three Complementarian Approaches

Within a complementarian framework, at least three approaches to ecclesial leadership are possible. All three affirm that God created men and women to complement one another; they differ in how they understand the relationship between gender and authority and in the contextual expressions they consider acceptable. All three perspectives are currently represented in Fellowship churches:

1. Hierarchical complementarianism (fixed pattern)

This position holds that complementarity includes a hierarchical order in which women are always under male authority, and that this order should be reflected in both church and family. The patterns and commands found in Scripture are understood as universally binding not culturally conditioned. Therefore, women are excluded from serving as pastors, elders, or leaders with spiritual oversight in any cultural context. Even if some women are gifted for pastoral ministry, God’s design reserves authoritative leadership roles for men in order to preserve distinct complementary roles and maintain stable ecclesial and family structures. Compromising this order is seen as undermining God’s purposes for both church and home.

2. Hierarchical complementarianism (contextual expression)

This approach also affirms male authority in church and family as part of God’s created intention and as a signpost toward the kingdom in its fullness. However, in contrast with the “fixed pattern” approach, it recognizes that cultures differ and therefore leadership structures need appropriate contextual expression in order to uphold both complementarity and the church’s mission. It therefore acknowledges the gifting and calling of women to serve in significant pastoral or ministry roles (for example, as associate pastors), while reserving the role of lead pastor or highest oversight for men. In this view, pastoral ministry is primarily functional—an act of service—while hierarchical order is maintained through male-only senior leadership.

3. Non-hierarchical complementarianism (the view advanced in these articles)

This position also affirms male–female complementarity as a created good that produces wholeness and shared strength. However, in contrast with hierarchical complementarianism, it argues that God-ordained gender differences do not include hierarchy or restrictions in leadership roles. Authority and decision-making based on male–female distinctions are understood as cultural expressions rather than timeless divine mandates. While women may, in many settings, pursue leadership less often than men, exceptions are not viewed as violations of God’s order. In the kingdom inaugurated by Christ, spiritual gifting, authority, and responsibility are not distributed according to gender.

The proposal of these articles is that complementarity in creation should be affirmed, protected, expressed, and celebrated in both church and home, while also believing that prohibiting women from ecclesial leadership is not required in order to remain complementarian. These articles seek to demonstrate that the full participation of both men and women in kingdom service—including ecclesial leadership—can be understood as biblically faithful and consistent with a complementarian reading of Scripture.

If this is accepted, unity within the Fellowship can be upheld by acknowledging that context legitimately shapes how complementarity is expressed. What follows is an application of the hermeneutical approach advocated in these articles, which points to the belief that hierarchy and authority based on gender is not part of God’s design for kingdom living. On that basis, excluding women from ecclesial leadership can be understood as a contextual expression in some settings, while other contexts may—without compromising biblical faithfulness and with God’s blessing—appoint women as pastors, leaders, and elders.

Applying the hermeneutic to explore the validity of non-hierarchical complementarianism

Cultural limitations that require the hermeneutic

As has been argued in previous articles, our interpretation of the culturally conditioned biblical text is inevitably shaped by our own cultural context.[1] The questions we bring to the text and the way we move from text to application are guided by our social location. Those living in settings where their culture is dominant may be less aware of how culture influences interpretation, but by learning from others with different perspectives we gain a deeper appreciation for how God uses his word to communicate his message and build his kingdom.

The biblical world was patriarchal, and the teachings of Scripture reflect that hierarchy. In our Western society, such patterns feel inappropriate or even offensive. The idea of Sarah calling Abraham her “lord” (1 Pet 3:6), or Paul’s instructions about head coverings based on the claims that “the head of every woman is man” and “woman is the glory of man” (1 Cor 11) are not practices commonly found in Canadian churches. Yet in New Testament times, these were accepted and meaningful cultural expressions of male–female relationships.

Are we, as Western evangelical Christians, required to adopt the cultural practices reflected in Scripture even when our own culture views them negatively or when they carry little or no significance? For example, head coverings today may be worn by either sex for warmth, protection from rain and sun, or fashion. In our low-context culture, they are seldom symbolic or invested with relational or theological meaning.

So, are the social patterns assumed in these passages transcultural—universal structures ordained by God—or do they represent one of several legitimate human social arrangements through which God can accomplish his purposes? Can God work through different cultural structures and priorities without endorsing the culturally conditioned hierarchies described in the biblical world? Is it possible to interpret texts that appear to limit women’s leadership through alternative social lenses, resulting in a biblically faithful yet non-patriarchal theology? Or is gender-based authoritative hierarchy part of God’s design for the church?

How do we faithfully move from the culturally embedded message in the New Testament context to appropriately contextualized obedience in our own without distorting the divine message?

At least three responses are possible, corresponding to the three approaches described above:

- Hierarchical complementarianism (fixed pattern): Patriarchy is accepted as God-ordained; women should relate to their husbands as Sarah did in her declaration of Abraham’s authority and wear head coverings to show submission. This reflects a diffusion approach[2] in which New Testament cultural structures are transplanted directly into our context.

- Hierarchical complementarianism (contextual expression): Gender hierarchy is viewed as God’s intended design, but the biblical expressions require adaptation in order to communicate the same message in culturally acceptable forms today.

- Non-hierarchical complementarianism: Patriarchy is understood not as God’s design but as a human cultural construct, unnecessary in other contexts. Nevertheless, God’s intentions for relationships between men and women can be discerned within these passages. These truths reveal kingdom values and should be expressed in ways that resonate within our own culture.

Although people may (and do) hold any of these positions, arguing for one over the others often has limited value because each begins with different assumptions. Accepting this frees us from beginning discussions focused on specific passages or even by considering our assumptions. Instead, we can acknowledge our shared limitations in understanding God’s Word: we can only obey after interpretation, we can only interpret through a cultural lens, and we can only do theology from a human perspective.[3]

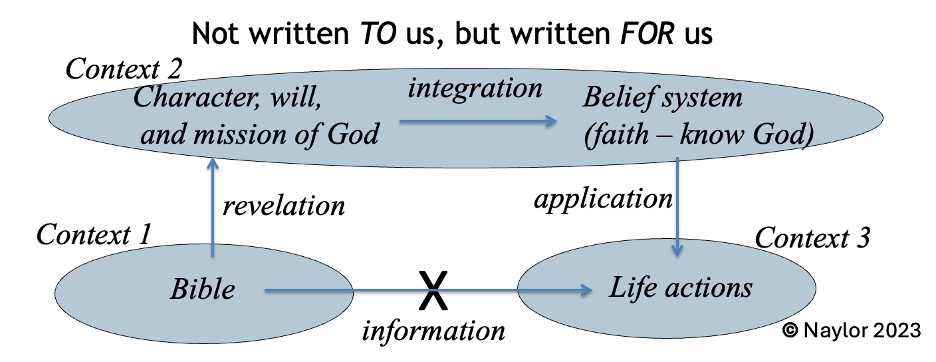

For that reason, clarifying how we read the Bible provides the necessary foundation for evaluating our assumptions and for engaging thoughtfully with the passages at the center of the discussion. The hermeneutic proposed here reads Scripture as God’s revelation of His will, character, and mission so that we may be conformed to the likeness of Christ. By engaging the divine Author before anything else, we create space for grace toward others even as we evaluate our assumptions, convictions, and applications.

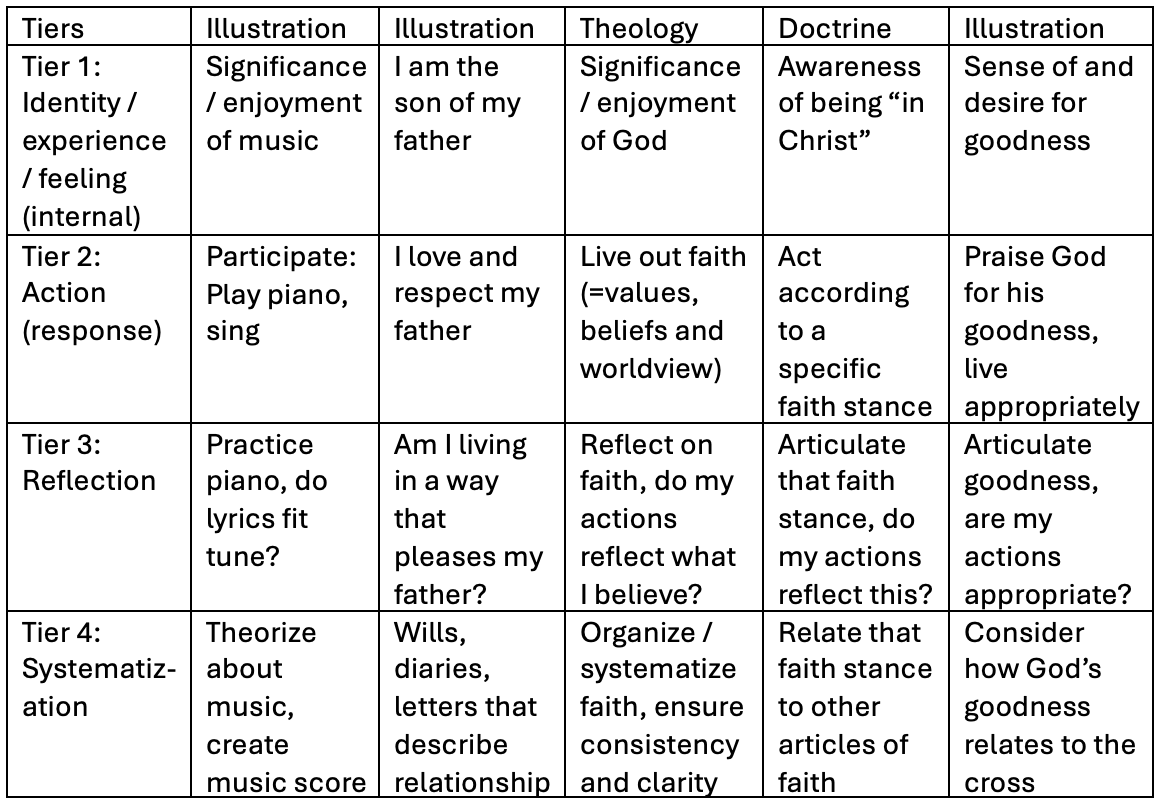

The hermeneutical process of reading the Bible as revelation addresses human limitations when determining how to be obedient to the word of God. These limitations were described in the article “Part 1: Reading the Bible as Revelation,” and duplicated here. When we read the Bible,

- We always interpret from a theological perspective, which is a human construct developed over time through exposure to God’s revelation and other influences.

- We always interpret from an enculturated position, using the language and concepts granted to us from our context.

- Communication is complex and requires dialogue within community to move to appropriate action and application.

- As fallen humans we are limited and prone to misunderstanding and inconsistency. Humility before God and openness to correction is required.

- Biblical concepts such as “authority” and the implications of “gender” should not be assumed when reading a verse. Rather, we need to recognize the influences and assumptions that shape our theology (faith) and then test them.

- We cannot assume that even a “clear” verse is properly understood. Because of the historical and conceptual distance between us and the original author/audience, there are contextual dilemmas and tensions that are not immediately obvious.

- Obedience is not about following rules and emulating biblical patterns, but conforming to God’s revealed will, character and mission.

- Conforming to God’s revealed will, character and mission requires expressions that are contextually meaningful.

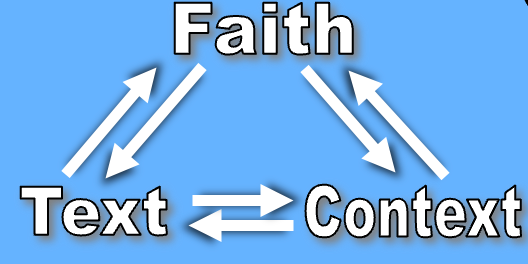

- We are constantly engaging in a dialogical process between theology (faith), text (Scripture) and context (the influences that shape our thinking and understanding of reality).[4] This liminal reality is our human condition that encourages us not to establish practices based on a few verses, but on a robust theology[5] that reveals God’s deeper purposes. Only then can we confidently apply our conclusions to ecclesial contexts today.

Steps to examine disputed verses

The following steps taken from the summary of the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation, also found in “Part 1: Reading the Bible as Revelation,”will be used in the consideration of the disputed verses:

1. Approach the passage as God’s self-revelation. Read Scripture primarily to know God, not as a manual of instructions to follow.

2. Recognize the differences between the biblical context and your own. Acknowledge the cultural, linguistic, and historical distance between the ancient world and today, and avoid assuming that biblical commands or practices can be applied directly to your setting.

3. Focus on the divine Author to avoid misapplying cultural forms. Discern God’s will, character, and mission in the passage and avoid treating culturally conditioned behaviors as timeless mandates.

4. Form a theological framework for the text. Asking what the passage reveals about who God is, what God desires, and what God is doing, requires consideration of a broader theological vision of Scripture in order to discern God’s kingdom purposes and gospel-shaped intentions.

5. Conform your life to God’s self-revelation in order to know him. Let the character, purposes, and mission of God—seen both in the passage and in Scripture as a whole—shape your response to the passage.

6. Develop a culturally appropriate expression of obedience. Live out the text in a way that

- Navigates cultural differences,

- Remains faithful to what Scripture reveals about God, and

- Embodies God’s purposes in the local body of Christ.

Applying the hermeneutic

The verses we will address with this hermeneutic are 1 Timothy 2:11–15

“Let a woman learn quietly with all submissiveness. I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man; rather, she is to remain quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve; and Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor. Yet she will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith and love and holiness, with self-control” (ESV).

and 1 Corinthians 14:34–35

“The women should keep silent in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but should be in submission, as the Law also says. If there is anything they desire to learn, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church” (ESV).

The following description outlines the proposed hermeneutical process for considering these verses. Rather than an attempt to be comprehensive or even to consider all the questions, it provides examples and a framework within which a fuller exploration—including careful exegesis and ongoing dialogue—can take place.

1. Approach the passage as God’s self-revelation

Read the passage with the desire to discern God’s will, character, and mission that will guide us to participate more fully in His kingdom. We do not read the passage to extract directives (e.g., women must be silent, not teach, or refrain from authority), but to ask how it reveals God’s character, expresses His desire for the gathered church, and advances His mission. In other words, we ask the sincere question of a child seeking to fulfill the Father’s will, “Why was this command given?”[6]

2. Recognize the differences between the biblical context and our own

Because of the nine limitations outlined above and explored throughout these articles, the epistles should not be read as universal, normative instructions but as case studies of how the writers guided first-century believers to live out the gospel in their specific contexts. They were not written “to us,” but they were written “for us.” Therefore, they continue to guide us authoritatively as we submit to their teaching within the larger context of God’s purposes.

A rigid, literal application of Scripture without attention to differing contexts leads to conclusions that distort Jesus’ intentions for us. The universal intent of a command is realized only as we faithfully embody God’s kingdom and mission within our own context. In this, we follow the apostles’ example—discerning the way of the cross and expressing the gospel in concrete, contextually fitting ways.

3. Focus on the divine Author to avoid misapplying cultural forms

Submission to these passages is not fulfilled by adopting the practices of the early church or by following commands literally. We should avoid transplanting culturally conditioned first-century practices into our context as if they carry the same meaning or as if literal compliance constitutes obedience. Instead, we translate God’s intention into faithful and contextually appropriate expressions.

Appropriate translation occurs by discerning the kingdom purposes behind the practices described—how they reveal the will, character, and mission of God. We then conform ourselves to that vision and seek fitting ways to express God’s purposes within our own cultural setting. In this way, the congregation becomes “the hermeneutic of the gospel,”[7] following the apostolic pattern of engaging culture through the lens of the gospel and embodying it in forms that communicate God’s truth today.

4. Form a theological framework for the text.

We engage these passages theologically when we recognize that the commands they contain are not intended as universal, literal directives for all times and places. Rather, Paul was expressing the will, character, and mission of God in ways appropriate to a particular audience within its historical and cultural context. Our task, then, is to ask why Paul gave these instructions and how they helped believers live as God’s people in that situation.

We do this by considering Paul’s concerns and responses through the lens of our gospel-shaped theology—the faith by which we have learned to live and act as a Christ-centered community. Even as we come to these verses, we already hold theological convictions about leadership and gender grounded in Jesus’ teaching and expressed within our own cultural context. These form the lens through which we approach the text, even as the passages themselves refine our theology by revealing more of God’s will, character, and mission.

In short, these verses are not fixed rules to replicate but case studies that contribute to an ongoing dialogue through which we grow as God’s people. They are examples from which we learn how to embody redemption and cultivate Christ-centered relationships within our community. The following are examples of a prior theologies that we can bring to the text.

Kingdom theology as primary

Because we are Christians and believe that the coming of the kingdom overturns worldly values and priorities, placing them in their proper order under heavenly priorities, it is essential that any theology of gender and authority be developed within the framework of what it means to be “in Christ.” When we take Jesus’ kingdom priorities and values seriously, we begin by considering the shared status of all believers—men and women alike—as heirs and co-heirs with Christ (Rom 8:16-17). This shared status provides the primary theological context within which questions of gender roles in the church must be addressed.

For example, Jesus revealed kingdom priorities by (1) reworking the commands of the Law to disclose God’s intention (Mt 5)[8] and by (2) articulating God’s purpose for marriage as an indissoluble union (Mt 19:3–9). That is, Jesus did not reiterate the commands of the Laws; he emphasized the intent of those laws in a way that revealed God’s purpose and heart. Similarly, the revealed status of men and women within the kingdom must serve as the lens through which we engage the so-called prohibition passages and develop a theology of gender and authority.

We therefore begin by asking what it means for both men and women, as members of the kingdom, to be included as “brothers” (adelphoi; Rom 1:13; 8:12, 1 Co 1:10-11), counted among “sons of God” (huioi theou; Rom 8:14–16; Gal 3:26ff), named as “kings and priests” (1 Pet 2:9–10; Rev 1:5–6), receive the Spirit, see visions and prophesy (Acts 2), assigned to serve, make disciples, and build up the body of Christ (1 Co 12), called to reign (Rom 5:17, 2 Tim 2:12, Rev 5:9-10, 20:4), and crowned with authority to lay before the throne (Rev 4:10).

These kingdom realities provide a key theological foundation for our ecclesiology, since every contextual expression of the body of Christ should faithfully reflect the values, identity, and structures of the kingdom itself. Therefore, expressions of church ministry—for both men and women—should make room for the full range of what it means to live “in Christ.”

Creation as a guide towards a theology of gender

Beyond a consideration of gender status within the kingdom, we might also approach these passages through a theology of gender rooted in God’s intention for male–female and husband–wife relationships in Genesis. This is especially fitting in light of Paul’s reference to Adam and Eve in the passages we are considering. Adam is created first, and Eve is created as a “helper” (Gen 2:18). The Hebrew term ezer does not imply a secondary or inferior role within a hierarchy. Rather, it describes Eve’s role in completing what Adam lacks so that together they become one (Gen 2:21–24). Notably, ezer is most often used of God as our “helper” in times of need (Ex 18:4; Deut 33:7; Ps 70:5), indicating strength and essential support rather than subordination.

Thus, the biblical picture of husband–wife relationship is fundamentally complementary, rather than hierarchical. This complementary unity is presented as the basis of their shared purpose and life together. As George MacDonald[9] observes:

one of the great goods that come of having two parents, is that the one balances and rectifies the motions of the other. No one is good but God. No one holds the truth, or can hold it, in one and the same thought, but God. Our human life is often, at best, but an oscillation between the extremes which together make the truth; and it is not a bad thing in a family, that the pendulums of father and mother should differ in movement so far, that when the one is at one extremity of the swing, the other should be at the other, so that they meet only in the point of indifference, in the middle; that the predominant tendency of the one should not be the predominant tendency of the other.

Much more could be said in forming a robust theology of gender, but this illustrates why such theology matters when engaging disputed passages. We seek to live faithfully with the insight we have, while remaining open to continued refinement through dialogue with Scripture, with other believers, and with our cultural context.

A theology of authority

We can also consider a theology of authority in leadership as it relates to these verses: How does authority function in the kingdom according to Jesus’ teaching?

In the Gospels, the disciples frequently worried about rank and power—who would sit at Jesus’ right and left, who was greatest, who had authority over whom (Mt 18:1; 20:20–24; Mk 9:33–34; Lk 9:46; 22:24). Jesus rebuked such thinking and demonstrated the true nature of leadership in the kingdom by washing His disciples’ feet (John 13).

In the kingdom, those who lead are those who serve. Both women and men are called to serve one another and metaphorically wash each other’s feet—this is the true standard of leadership in the church. Jesus did not establish a human hierarchy of dominance. Authority rests not in status or position but in relationship to Jesus. God has not delegated authority for individuals to rule over others in the church (Jesus alone is head of the church – Eph 1:22-23; Col 1:18); authority remains in his Word and is exercised through His Spirit. The focus for leaders is that of responsibility for others for which they will give an account (Heb 13:17; Jas 3:1; 1 Pet 5:2-4).

Viewed through this lens, Paul’s concern in these verses about the exercise of authority can reasonably be interpreted as a condemnation of the misuse of authority—not the establishment of gender-specific authority.

When we approach these verses within a broader theology that understands women as full participants in the life of the church, we can affirm that the spiritual equality of men and women should be reflected in forms of servant leadership that embody the will, character, and mission of God. A well-formed theological framework enables us to discern God’s priorities and protects us from treating culturally conditioned biblical instructions as rigid rules to be replicated. As argued above, kingdom identity precedes and guides role differentiation, and the authority shared by all believers is exercised as worshipful participation in—and submission to—God’s rule.

5. Conform your life to God’s self-revelation in order to know him

The question remains: if the non-hierarchical complementarian theology presented here aligns with Paul’s own theology, what concern is driving these two verses that appear to restrict women’s leadership in the Corinthian and Ephesian churches? Many reasonable explanations—based on exegesis and historical context—suggest that Paul was addressing local rather than universal issues. Still, even if we set those possibilities aside, the hermeneutical approach proposed here invites us to discern how these verses express God’s will, character, and mission in ways that advance the kingdom and build up the community—rather than using them to restrict the freedom and calling believers—including women—have in Christ. Such actions may be elevating a perceived law above “doing good,” even as the Pharisees’ use of the Sabbath offended Jesus (Lu 6:6-11; 13:10-17; 14:1-6, Jn 5:1-18; Jn 9:1-41).

A robust ecclesial theology that reflects God’s will, character, and mission helps us understand Paul’s concern in these passages. His aim is not to impose universal restrictions but to address specific local issues recognizable to the original audience. Because those concerns arise from God’s purposes, they remain relevant for us—these teachings are “for us.” But faithfulness does not mean shortcutting interpretation or applying commands universally through our own cultural lens. Instead, we must discern God’s heart for the churches being addressed and then pursue contextually appropriate expressions of the same kingdom priorities in our setting.

Obedience as ultimately intended by the Father is not demonstrated by literal compliance to a command (although the spirit of submission in such compliance is pleasing to God), but by engaging each command within the broader theology of God’s purposes—developing a vision of the Father and a desire to live in a manner that pleases Him.

This paradigm for obedience is not contrived as if the motive is that we find these specific verses offensive and want to explain them away—that would be inappropriate and unfaithful. Instead, this hermeneutic applies consistently to all biblical commands. Jesus emphasized this in Matthew 5 by moving beyond rule-keeping to a deeper, transformative obedience: “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” We pursue that perfection not by rigidly following commands but by understanding God’s heart and aligning our lives with his character and purposes.[10]

As noted earlier,[11] biblical commands function like a parent saying to a child, “Don’t touch the stove!” Maturity involves discerning the loving intention behind the instruction. A grown child honors the parent’s heart—not by avoiding the stove forever, but by using it wisely. Likewise, as we grow in our understanding of God’s purposes, we learn how to live out His commands in ways that express the life he desires, not mere compliance.

As a caution to those who use these verses to rebuke women in their calling to ecclesial leadership, we should consider Jesus’ interaction with the Pharisees and teachers of the law in Matthew 15. They had elevated certain laws—specifically vows to God—above the biblical command to honor parents. Their issue was not ignorance of God’s law, but a misinterpretation shaped by human cultural assumptions. As a result, their application of Scripture harmed relationships and opposed God’s intention, and so Jesus rebuked them.

In that same passage, Jesus declared that strict adherence to food laws—clear biblical commands—does not determine a person’s purity before God. Instead, purity and acceptance by God is a matter of the heart. Insisting on rules that hinder a person’s desire to serve God may become a form of “quenching the Spirit” (1 Thess 5:19) undermining God’s desire for that person.

The purpose of this hermeneutical step is to allow these verses to play a role in shaping our theology and then to live according to that theology so that we may know Christ. Misapplication of commands arises when we fail to account for our contextual limitations and do not discern God’s heart behind those commands.

6. Develop a culturally appropriate expression of obedience

Understanding is not enough; we are called to act and to conform our lives to God’s will. Faithful obedience requires navigating the tension between the cultural values of our setting—many of which resist biblical teaching—and God’s contextually conditioned commands, which reveal His will, character, and mission and must be embodied appropriately in our own context. Jesus himself faced such a dilemma when asked about paying taxes to Rome (Mt 22:15–22). Rather than choosing between two rigid options, he redirected attention to the deeper reality: God’s image is stamped on humanity. Faithfulness begins by recognizing our identity and the One to whom we belong. We obey by using every passage to align our lives to his desires and purposes.

In response to my friend’s question[12]—“How can you believe that a woman can serve as a pastor or leader in the church when the Bible clearly commands otherwise?”—the issue is not whether we reject Scripture on one hand or adhere to it in only one acceptable way on the other. The deeper call is to ask, “Why was this command given?” That is not rebellion or worldly doubt, but the sincere posture of a child seeking the Father’s will. True obedience means discerning the gospel purpose behind the command and expressing it in contextually appropriate ways that reveal God’s will, character, and mission today.

Afterword: Appeal to Unity

We do not follow trends, nor do we cling to traditions—we follow Jesus. Whatever convictions churches have discerned from Scripture, we want to ensure freedom to apply those convictions with joy rather than compulsion. Obedience to God’s revelation is worship: a declaration that his kingdom purposes are good. We encourage churches to submit to God’s authority and trust his word, even when their conclusions are unpopular or others disagree.

No side of the debate over women in ecclesial leadership should be characterized as rebelling against God or as having capitulated to cultural pressures. Fears that those who hold a different position have been unduly influenced—or even seduced—by culture are misplaced. In the book of Revelation, John offers a vivid portrayal of the conflict between two kingdoms. As de Silva observes, “When John takes us to look even closer into the activity of the world in rebellion against God, we see a movement afoot to steal away the worship due the One God and to draw as many people as possible into a lie that leads them away from the true center.”[13] On every side of this debate within our Fellowship, there is admirable jealousy for the “worship due the One God,” a shared passion for the kingdom of God and a common prayer, offered with Jesus: “Thy kingdom come” (Matt 6:9 KJV).

Therefore, we must not reject churches that affirm women in ecclesial leadership as disobedient or rebellious. Nor should we shame as legalistic those who hold to male-only leadership. This is not a salvation issue, but a discipleship issue—a matter of conscience and of ordering our lives in ways we believe honor God. Whatever path is taken must arise from submission to God and joyful conformity to his purposes.

Our desire as members of Fellowship churches is to learn with humility, seeking to read and apply Scripture in ways that reflect God’s heart. Dialogue with those who hold different convictions is essential—marked by grace, patience, and openness—so that together we may see what we have not yet seen. Our brothers and sisters throughout the Fellowship love and serve God wholeheartedly; we are called to affirm that devotion and pursue unity in diversity as we seek to glorify God together.

Let us resist the temptation to relieve the tension through division. Instead, let us practice patience with those who differ, recognizing that we are all on a journey of theological growth—a journey shaped by love, clarity, gentleness, and reverence. Rather than shaming or dismissing one another, we shepherd one another as followers of Jesus.

Practically, all sides of this issue offer valuable perspectives and encourage healthy tension. We are tethered to each other, able to challenge, inform, and correct one another. If we divide, that tether is cut, and each side becomes more susceptible to extremes without the balancing influence of the other.

This is not an issue worth dividing over—nor should it be ignored. When we focus on what unites us and our service and obedience are sincerely directed toward honoring God, we can make space for contextualized expressions of faith that glorify his name and welcome differing perspectives that help us continue questioning and growing.

Soli Deo gloria.

[1] See Part 3: Why we ask “why”: The Limits of Culture and Language.

[2] Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1989), 7,8 (see Part 3: Why we ask “why”: The Limits of Culture and Language).

[3] See Part 5: Developing theology through the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation.

[4] See Part 4: A Framework to guide the Process of Interpretation.

[5] A good friend challenged the idea of a “robust theology,” stating that “Even many in my acquaintance who have been believers for decades would hesitate to say that they have a robust Biblical theology.” As explained in Part 5: Developing theology through the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation, “robust theology”refers to the ongoing development of sincere faith as believers—”children and adults, the literate and illiterate, believers and seekers alike”—live out their commitment to follow Jesus as they find him revealed in God’s word.

[6] See Part 5: Developing theology through the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelationfor a detailed explanation of how this interpretive process can be applied.

[7] This is based on the title of Chapter 18 in Lesslie Newbigin’s book, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 222.

[8] See Part 6: Biblical support for the proposed hermeneutic.

[9] George MacDonald. “The Seaboard Parish,” Chapter 2 in George MacDonald: The Complete Novels, (Kindle Edition 1869), 1496.

[10] See Part 6: Biblical support for the proposed hermeneutic for a further development of this argument.

[11] See Part 1: Reading the Bible as Revelation.

[12] See Part 2: True Obedience: Embracing the Heart of God.

[13] David A. deSilva, Unholy Allegiances: Heeding Revelation’s Warnings (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2013), 43.