Response to Mack Stiles’ article “What Could Be Wrong with ‘Church Planting’? Six Dangers in a Missions Strategy”

I appreciate Stiles’ irenic tone in which he seeks to point out “weaknesses” and give “cautions” for “Church Planting Movements” (CPMs) or “Disciple Making Movements” (DMMs). Such push back is important in missions since we all have blind spots and can get excited over new developments without noticing potential problems. The need for careful examination is especially true for us in Fellowship International since we are promoting and investing in a DMM strategy. Where the weaknesses or cautions are invalid, we need to have a good argument for why we see things differently. Where they are valid, we need to be alert and avoid the danger as much as we can even as we move ahead.

For ease of reference, the following 9 responses are provided in the order they appear in Stiles’ article.

- Critique: Local rather than Biblical Culture (under Critique 1. Sloppy Definitions of Church)

Because CPM advocates say that they “don’t want Western church,” Stiles assumes (correctly) that CPM advocates want a church that is contextualized within the local culture. He opposes the idea of producing “a church that imitates local culture,” claiming that the goal is a “biblical culture.” He goes on to explain that ethnic and cultural identities should not be erased, but should be “secondary to our new identity as the people of God.”

Summary answer: God intends churches to be culturally appropriate expressions of the body of Christ.

Detail: Stiles’ concern is that any expression of church should not compromise God’s intention for the body and bride of Christ with the “blindnesses and brokenness” of any culture. This is important and should be affirmed. Where he errs is by stating that a church should not “imitate” culture, which implies that it should not be a part of, or an expression of culture. In fact, missiologically speaking, the opposite is true: each congregation should “own” both gospel and church as an essential part of their culture, rather than as a foreign import.

Stiles’ error is partly categorical and partly theological. “Biblical culture” in the sense Stiles is using the term is a different category than is intended by referring to human “cultures.” Anthropologically speaking, “culture” is the way a self-defined group of people create meaning in their interaction with their environment. It is the “total process of human activity” which comprises “language, habits, ideas, beliefs, customs, social organization, inherited artifacts, technical processes, and values” (Niebuhr, 1951. Christ and Culture. p. 32) within any given community. It is therefore impossible for a church to exist without worshiping and serving through cultural expressions. Similarly, it is necessary for an individual to maintain their cultural identity on one level while claiming a new identity as a child of God. These two aspects are not contradictory, but complementary.

By using “biblical culture,” Stiles is likely referring to biblical values and principles that believers are to live by within their culture – a necessary and appropriate goal. But he has used “biblical culture” in a way that wrongly implies a contrast with the local culture. Because “biblical culture” cannot replace a local culture nor fit within the definition of culture as described above, it belongs to a different category. Using “biblical culture” as if it is a substitute for local culture ignores the reality that the changes the gospel brings occur in and through culture, rather than supplanting it. A simple example that demonstrates this misuse of the term “biblical culture” is language. Language is an integral part of any culture. If one culture was supplanted by another, the first culture would lose its language, among other things, because the dominant culture’s language would replace it. However, it is not the goal of any missionary to replace a local language with a “biblical language,” any more than a local culture should be replaced with a “biblical culture.” In fact, when one culture assumes the use of its language in worship, it can be an indication of the dominant culture imposing itself upon another people group rather than respecting the depth of identity and significance found in each culture. Lamin Sanneh (1989) powerfully argues for the “translatability” of the gospel (with parallel implications for the church) in Christian mission in Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture. This approach to culturally shaped expressions of church and gospel is in contrast to the Islamic orientation towards its mission: “[C]ultural diversity belongs with Christian affirmation in a way that it does not with Islam” (p. 212).

Theologically, Stiles’ mistake is a lack of recognition that both gospel and church are intended by God to have unique cultural expressions, rather than importing or imposing gospel and church expressions from one culture to another. Of course, Stiles’ argument is not that a foreign culture should dominate; his concern is that a church should conform to biblical teaching, rather than to culture. However, this is a false dichotomy; there is no church or gospel without culture. “Biblical teaching” is analogous to content while culture is analogous to language. Culture is the “language” through which the “content” of human thought or action finds expression. Thus the incarnation of Jesus is God’s expression of salvation within human life and culture; God’s salvation did not occur in a cultural vacuum. Culture is the locus of gospel and church, and they cannot exist separate from it. Culture is to be redeemed; it cannot be avoided.

In Acts 2 the disciples begin proclaiming the gospel in other languages, a theologically profound message from God of how he accepts all cultures as the media within which church and gospel find expression. The rest of the book of Acts and the Epistles are lessons of how contextualization of the gospel message and church takes place in different cultural settings. The consideration of circumcision in Acts 15 is a prime example, as well as the rejection of clean and unclean food distinctions (Mt 15, 1 Cor 10). Part of the apostle Paul’s amazement in discovering the “mystery” of God’s plan was how God’s intention was to include other cultures in “God’s household” (Eph. 1-2) – a unity that embraces cultural diversity. Contextualization within a local culture is the methodology that all missionaries should aspire to, as expressed by the CPM missionaries quoted by Stiles: they did not want their own cultural preferences to override local expressions of church.

- Critique: Speed (under Critique 1. Sloppy Definitions of Church)

Stiles suggests that churches should be established on biblical principles and “here’s the rub: it takes time.” At the end of the article he repeats the idea with “Speed is not the call.” The implication is that CPMs and DMMs are focusing on getting the work done quickly.

Summary answer: the concern in CPMs and DMMs is not speed, but multiplication.

Detail: The danger of prioritizing efficiency and speed in church planting is a valid concern because as humans we look for shortcuts and want results now. A harvest requires patient waiting for the plants to germinate, grow and mature. God usually does things slowly and missions is a slow and methodical process because it focuses on building relationships. Nonetheless, the implication that DMMs are trying to bypass the more appropriate, but slower, path of God’s church planting methodology, is unfair and misses the point. The goal of DMMs is not speed, but multiplication. The vision and hope is one of planting the Gospel in “good soil” resulting in an exponential response with a vast “harvest.” Because this is a biblical vision given to us by Jesus, it is a possibility and something God wants to bless.

Stiles focuses his criticisms on the word “church” in “Church Planting Movements,” but the key to this phrase is the last word: “movements.” The vision of DMMs is that the Gospel can be spread through a multiplication process whereby those who are learning to obey Jesus through studying the Bible can pass that “virus” of disciple making on to others. The power in the DMM dynamic is the move away from leadership-heavy organizations towards disciple making movements in which all believers are encouraged to (1) use the Bible as the primary authority and to obey what it says, and (2) spread that methodology through their relationships with others.

Is it valid to encourage believers early in their walk with Christ to lead a Bible study with unbelievers or other new believers? Or should the process be slowed down with a greater reliance on the teaching of trained leaders within traditional church structures and processes, as Stiles prefers? Church history suggests that there may be a pendulum effect between the passion of movements spreading the gospel quickly, and the establishment of organizations. As churches form and communities are organized with pastoral leaders, the fire of multiplication stimulated by apostolic leaders dies down and a “new normal” in the community is established. Perhaps, because of global communication, we are able to observe something like this pendulum happening today – the complete life-cycle of the rise, establishment, stagnation, and demise of faith can be seen in real time around the world. These expressions have their parallel in the NT as seen in the celebration of thousands coming to Christ in one day in the book of Acts, the establishment of Christ-centered believers in a particular locality throughout the Epistles, and the threat of at least one church having their “lampstand” removed in Revelation.

Stiles cites with approval the suggestion of a friend that Paul’s extended time in Ephesus (3 years) indicates that he “delayed total indigenous leadership.” Perhaps this was not “delay” but a time to raise up leaders so that Paul could move on. If leaders were prepared so that Paul could leave, then it is likely they were serving as leaders very early on, maybe even leading studies of the Scriptures, so that Paul could feel comfortable leaving. This latter scenario fits well with the DMM call to raise people up quickly into a disciple making ministry. This is not incompatible with training and appointing leaders; effective DMMs demonstrate good strategies for developing leaders.

In his conclusion, Stiles suggests that people “dial it back.” This is an unfortunate choice of words. When there is a movement of God’s Spirit toward revival, or even people working and praying for revival where results are few, I don’t think the advice should be to “dial it back,” but to “bring it on.” I would not criticize his methodology of church planting that he describes near the end of the article. It is one way to go about the task. But I would suggest that perhaps even his church’s approach to “grow and teach and model and correct” may find benefit through adopting and adapting some of the CPM practices that he is criticizing. It may also be true that established churches that are taking it slowly could benefit from the fire of a passionate pursuit to obey Jesus that is seen in DMM movements.

- Critique: Calling gatherings “Church”(under Critique 1. Sloppy Definitions of Church)

Stiles’ experience is that DMM practitioners demonstrate an “inability to define a church” and are promoting gatherings that are not biblical churches because they are not grounded in “basic foundational principles.”

Summary answer: A focus on making disciples is the way to a healthy and indigenous expression of church.

Detail: The key strength of DMMs is found in Stiles’ third “tweetable” sentence: “The overarching mission of the church is the Great Commission: to disciple all nations, teaching them to obey everything Christ has commanded.” This is where DMM begins, with the goal of seeing expressions of church emerge from gatherings that are shaped by their obedience to Scripture. The goal is for culturally appropriate expressions that include all the elements of a Christ-centered community. The DNA of the church is actually instilled from the beginning in the DBS process:

- Worship and praise

- Prayer and requests

- Engaging God’s word

- Conformity to God’s nature as revealed in Jesus

- Obedience to God’s will

- Evangelism

- Accountability

The DMM approach is not what Stiles is familiar with, or even comfortable with, but as long as the leaders of a movement remain biblically grounded and obedient, the establishment of commonly held truths (doctrine) should not be a problem. As Newbigin states (1989. The Gospel in a Pluralist Society. p. 222), “The congregation [is the] hermeneutic of the Gospel.” The goal of DMMs is for people to live out this principle as a congregation, centered on Jesus, within their context.

- Critique 2: Vulnerable to Error and Heresy

Stile’s states that “CPM calls for an extreme commitment to indigenous leadership, they often leave these young believers open to destruction”

Summary answer: This danger is not unique to DMMs and safety measures are built in.

Detail: When multiplication occurs, it is “messy.” In stable traditional church structures, hierarchal control keeps things in order under the guidance of recognized leaders. In DMMs, however, rather than maintaining a repository of truth in the hands of a few leaders, there is greater freedom and responsibility for average believers (disciples) to determine what God has revealed. This is done with group encouragement, input and correction in Discovery Bible Studies (DBS). There is potential for error and heresy. However, it is also possible for error and heresy to be entrenched within an ecclesial organization and perpetuated through the leaders. So this danger is not unique to CPMs and DMMs, but is a warning for all believers and church structures.

It could also be argued that DMMs principles hold the key for preventing and correcting error even more so than traditional church structures in which control of accepted truth is held by a few. In the DBS process, the Word, rather than a human authority, is the teacher. The focus is to discover what the Bible says, and people’s ideas are constantly challenged by the question, “where is that found in the passage?”

Furthermore, it could be argued that, historically, heresies have not arisen from the rapid spread of people engaging God’s word, but from those who proclaim themselves as teachers with special or authoritative insight into God’s Word. Again, in such a scenario, it is the ones steeped in God’s Word with a habit of seeking the truth (like the Bereans of Acts 17:11) who are less likely to be vulnerable to being led astray.

A word should be said about the “extreme commitment to indigenous leadership.” I suggest that the adjective “extreme” is a better descriptor of autocratic leadership found in hierarchical structures. DMM leaders are taught not to have confidence in their own experience and education, but to consistently lead people back to the Bible in a discovery process, making young believers less “open to destruction.”

Another concern raised is that “mature teachers and preachers are sidelined in the CPM model in the name of indigeneity.” Although I am not aware of an example of leaders being “sidelined” in CPM, it is true that CPM has a strong focus on empowering local believers to become competent leaders rather than relying on cultural outsiders. This does not mean that outsiders do not have a role to play, but the priority is on training insiders to become leaders as a way of encouraging multiplication. This can be appropriately described as a “commitment to indigenous leadership,” but it can scarcely be called “extreme.”

- Critique 3: Temptations to Pragmatism

Stiles’ fear is that people “jettison scriptural principles about the church” out of a desire for results.

Summary Answer: The solution is to continue testing all methodologies to ensure that they are consistent with Jesus’ mission and vision for the church as revealed in the Bible. Such a practice of testing the spirits in the light of Scripture is consistent with CPMs and DMMs.

- Critique: Missionary fad? (under Critique 3: Temptations to Pragmatism)

Stiles notes that “missionary strategies come and go” and suggests that CPMs fall under that category. He emphasizes this by saying that it is new (circa 2001) in the overall history of missions and yet old in the world of modern missionary methods. Since CPMs have morphed into DMMs as “a kind of next-generation CPM with a focus on obedience-based discipleship and discovery Bible studies,” this is more of a “missionary fad” rather than a “clear proclamation of gospel truth in the context of healthy biblical churches will last until Jesus returns.”

Summary answer: Identifying what God is doing in the world is responsible and appropriate.

Detail: The idea of “fad” is pejorative and quite unfair to and dismissive of this current movement in missions. It is much better to recognize that missionaries and missiologists have always looked for ways to describe what they see God doing and to share with each other those activities that have been fruitful. In this day of global communication, it is a positive and not a negative development that we can quickly discover and analyze where there is a movement of the Spirit so that we can seek to pattern our ministry after fruitful practices. Looking for healthy patterns is not new, it is a matter of respect for what God has done and is doing through his people. Two historical examples are the prayer meetings that preceded revivals in various parts of the world, and the three “self-“ principles (self-governance, self-support, self-propagation) promoted by Henry Venn and Rufus Anderson as a basis for the establishment of indigenous churches for the American and British Protestant mission in the 19th century.

It is also important to realize that any new methodology is constantly being tested and evaluated for biblical support and appropriateness to the task of seeing the message of the Gospel proclaimed and people being discipled and gathered into Christ-centered communities. Those who have become seriously involved in DMMs have critiqued the concepts and recognize that this approach is not a “magic bullet” or a “fad” but a process of engaging a culture using proven fruitful practices so that multiplication is encouraged and people are saved. It is not a “one size fits all” shortcut but an approach that takes both Bible and context seriously so that adaptation of the methodology occurs in each setting in such a way that integrity to the Word is maintained.

- Critique 4: Lack of Clarity

Stiles thinks that CPM is often “fuzzy” about biblical conversion and what constitutes the gospel.

Summary Answer: I do not know what Stiles is referring to. Since a major fruitful practice found in DMMs is to study and obey the Bible, people encounter Jesus as Lord and Savior in the Word. (I have a suspicion that Stiles may have a particular theory and formulation of the gospel and salvation that is used as a lens to interpret Scripture. See below on “Over-Contextualization”).

- Critique 5: Ethnically Homogenous Congregations

Stiles claims that “All churches should desire to be international churches.”

Summary answer: The “person of peace” principle looks for natural networks.

Detail: The concept of culturally homogenous churches actually has a strong and healthy history with respected missiologist Donald McGavran (1954) bringing the reality of family and kinship ties to prominence in his book The Bridges of God. He recognized that people have distinct ethnic identities and the gospel needs to cross cultural boundaries and become part of the worldview of a people group in order for them to be transformed by the gospel. God must “speak a person’s language” both literally and metaphorically. That is, the gospel must be seen as relevant for them to accept the message for themselves. Respecting other cultures prevents an outside culture from acting in a colonizing manner by forcing them into a mold.

An assumption of the DMM strategy is that in order for the gospel to penetrate and transform a people group, it must first be seen as speaking to them within their context. Their identity must not be compromised or overruled by those with a different cultural identity. Thus the principle of “person of peace” (POP) has been promoted. These POPs are the gatekeepers of a network who metaphorically open the door for others to engage God’s word.

Culturally distinct expressions of the gospel and the church are valued and not disparaged with DMMs. These varied expressions are considered to be like facets of a diamond – each providing insights that further the church’s appreciation for and worship of God. This picture is ultimately fulfilled in Rev 7 where a multitude of nations are before the throne, each praising in their own tongue and manner, reflecting their love for and submission to God.

While it is not wrong to be an “international church,” as Stiles insists, it is only one local expression of the universal church. It, too, has its limitations and difficulties that are not found in distinct ethnic expressions of church. A more inclusive and (I believe) appropriate approach is to encourage local churches to have an international agenda with respect to other churches and believers in a manner that maintains each congregation’s cultural and ethnic integrity. That is, they desire to be connected with their brothers and sisters across geographical and ethnic boundaries for fellowship and correction (For further reading, see my article, “Navigating the Multicultural Maze: Setting an Intercultural Agenda for FEBBC/Y churches” in Being Church: Explorations in Christian Community, 2007).

- Critique 6: Over-Contextualization

Stiles also believes that “Many involved in CPM … cut and paste the gospel, even giving different interpretations to clear biblical texts so that we can fit the gospel to culture, [and so give] up the biblical narrative.”

Summary answer: Stiles has confused syncretism with contextualization.

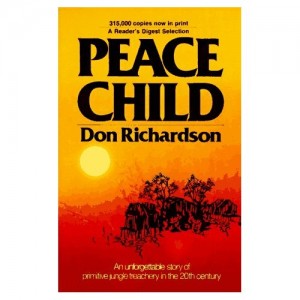

Detail: Contextualization is inevitable in our preaching and teaching, including the way the gospel message is communicated. The question is: does the message we present resonate with the culture AND maintain biblical integrity? If the message maintains biblical integrity, but does not resonate, we are in danger of creating dual systems. That is, we are presenting a foreign system that is added to the systems lived and understood by the insiders because it is not perceived as relevant to who they are. If the message resonates with the context, but does not maintain biblical integrity – i.e., the gospel has been compromised – that is syncretism. One of the best and well-known examples of good contextualization of the gospel is “Peace Child” (1976) written by Canadian missionary to New Guinea, Don Richardson. His first presentation of the gospel to the Sawi people was accurate, but did not resonate the way he intended – it was not appropriately contextualized. When he retold the gospel message with Jesus as the “Peace Child,” it resulted in a contextualized presentation of the gospel that maintained integrity with Scripture while resonating with the context. (For another example and further explanation, see my own contextualization journey among Sindhis).

Stiles has confused an appropriate representation of the gospel message that can be understood by the audience with a distortion of the gospel message due to some kind of compromise with cultural values. The way to deal with the problem of syncretism is not to have one particular presentation of the gospel that is considered universal – this only results in dual systems. It also reveals a mono-cultural blindness that says, “The way I express the gospel is the only true way,” and does not recognize that our own expression is also culturally shaped. The solution is to use the Bible as the final authority and ensure that people engage all the teachings of the Bible so that their beliefs and practices are challenged by what God has declared and what Jesus has revealed. There is a reason why the first four books about the life of Jesus the New Testament are called the Gospels. The gospel may be summarized into a short statement, but all such statements are contextualizations designed to fit a particular way of viewing the world and they come with unspoken assumptions. The full message of the gospel is as broad and deep as Jesus himself, who declared that he is “the Way, the Truth and the Life” (John 14:6).

References:

- McGavran, DA 1955. The Bridges of God: A Study in the Strategy of Missions. New York: Friendship Press.

- Naylor, M 2007. “Navigating the Multicultural Maze: Setting an Intercultural Agenda for FEBBC/Y churches” in Being Church: Explorations in Christian Community. Langley BC: Northwest Baptist Seminary.

- Newbigin, L 1989. The Gospel in a Pluralist Society. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- Niebuhr, HR 1951. Christ and Culture. New York: Harper & Row.

- Richardson, D 1976. Peace Child, Ventura: Regal Books.

- Sanneh, L 1989. Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture. Maryknoll: Orbis.

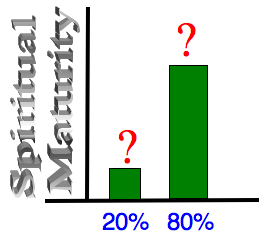

In my responsibility of providing outreach and missions resources to churches, I have come across a curious phenomenon. My experience is that there are a number of people in church leadership who do not have a positive view of the spiritual maturity and commitment of their congregation. Comments such as “a mile wide and an inch deep,” “20% do 80% of the work,” “half an hour after the sermon is over they don’t remember it, let alone apply it,” “they don’t take advantage of opportunities to go deeper,” and “they don’t know their Bibles” have been expressed in my hearing. Why this is curious is that my experience with the people of God in our churches has given me quite the opposite opinion. I have been constantly impressed, motivated and encouraged by the level of spiritual maturity and commitment to Christ in the people I meet.

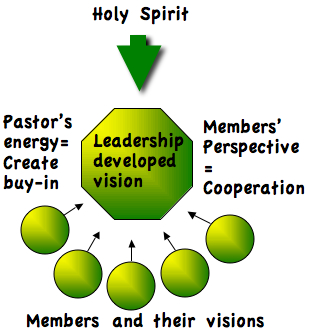

In my responsibility of providing outreach and missions resources to churches, I have come across a curious phenomenon. My experience is that there are a number of people in church leadership who do not have a positive view of the spiritual maturity and commitment of their congregation. Comments such as “a mile wide and an inch deep,” “20% do 80% of the work,” “half an hour after the sermon is over they don’t remember it, let alone apply it,” “they don’t take advantage of opportunities to go deeper,” and “they don’t know their Bibles” have been expressed in my hearing. Why this is curious is that my experience with the people of God in our churches has given me quite the opposite opinion. I have been constantly impressed, motivated and encouraged by the level of spiritual maturity and commitment to Christ in the people I meet. I have an uncomfortable suspicion that a significant part of this negative view of congregations stems from an inadequate approach to ministry by the leadership. The average church organization, whether labeled traditional, seeker sensitive or missional, has a leadership-driven program which members of the church are encouraged to support. The response by the congregation tends to be less than expected, especially if support has been indicated by a congregational vote.

I have an uncomfortable suspicion that a significant part of this negative view of congregations stems from an inadequate approach to ministry by the leadership. The average church organization, whether labeled traditional, seeker sensitive or missional, has a leadership-driven program which members of the church are encouraged to support. The response by the congregation tends to be less than expected, especially if support has been indicated by a congregational vote. A couple of months ago, Karen and I proposed to our church

A couple of months ago, Karen and I proposed to our church  I do not see that people are asking, “What’s in it for me?” Instead, they want to know, “Why me?” This is not a self-serving question. It is a self-identifying, individual question.

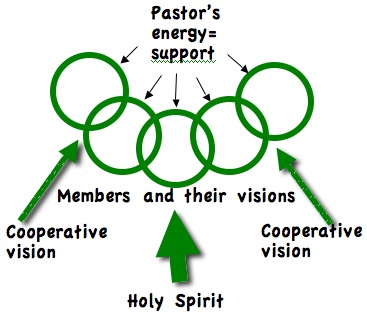

I do not see that people are asking, “What’s in it for me?” Instead, they want to know, “Why me?” This is not a self-serving question. It is a self-identifying, individual question. He plays the essential part of empowering leaders to pursue their callings and passions. He strengthens others’ obedience by creating a culture where they can say yes to the Spirit…. [All] the ministries he told me about happened away from the church. This same pastor went on to say, “I wouldn’t have a clue how to do what they do.” The very thought that clergy could preside over these kingdom expressions is ludicrous. Yet many congregational leaders do not trust people to minister out of their sight. (140)

He plays the essential part of empowering leaders to pursue their callings and passions. He strengthens others’ obedience by creating a culture where they can say yes to the Spirit…. [All] the ministries he told me about happened away from the church. This same pastor went on to say, “I wouldn’t have a clue how to do what they do.” The very thought that clergy could preside over these kingdom expressions is ludicrous. Yet many congregational leaders do not trust people to minister out of their sight. (140) “Coaches help people.” Coaching is a relationship…, not a program. It is focused on the [believer], not the program. You coach a [believer], not his or her ministry….

“Coaches help people.” Coaching is a relationship…, not a program. It is focused on the [believer], not the program. You coach a [believer], not his or her ministry….

Rajeev is a follower of Christ with a Hindu background who dedicated his life to Christian service as a young man. He is a talented musician who plays an eastern style drum, a teacher of adult literacy and an evangelist of the gospel of Christ. The drum is a perfect analogy or symbol for Rajeev’s approach to ministry. The drummer is not the lead instrument, but provides structure and support for the singers and other instruments. It does not dominate but enhances and guides. It leads from behind. With his mouth shut, Rajeev’s hands fly across the drum while others sing. This reflects the attitude that Rajeev has as he serves Muslims with the goal of showing them the light of Christ.

Rajeev is a follower of Christ with a Hindu background who dedicated his life to Christian service as a young man. He is a talented musician who plays an eastern style drum, a teacher of adult literacy and an evangelist of the gospel of Christ. The drum is a perfect analogy or symbol for Rajeev’s approach to ministry. The drummer is not the lead instrument, but provides structure and support for the singers and other instruments. It does not dominate but enhances and guides. It leads from behind. With his mouth shut, Rajeev’s hands fly across the drum while others sing. This reflects the attitude that Rajeev has as he serves Muslims with the goal of showing them the light of Christ. When he teaches adult literacy, an important goal for Rajeev is for students to teach others what they have learned in their first week of lessons. He quickly moves to the background so that his students can become the teachers and pass on what they have learned.

When he teaches adult literacy, an important goal for Rajeev is for students to teach others what they have learned in their first week of lessons. He quickly moves to the background so that his students can become the teachers and pass on what they have learned.