Recognizing the many influences that shape how we read and obey the Bible can make us more aware of our limitations, lead us to interpret with greater care and skill, foster a humble posture of ongoing dialogue, and help preserve our unity. All readers are invited to respond and challenge what I have written. I will be grateful for your insights and for continuing the conversation.

Some material in this article is based on my 2013 DTh thesis: “Mapping Theological Trajectories that Emerge in Response to a Bible Translation.”

NOTE: Chatgpt was used for editing, but not generative purposes.

Part 4: A Framework to guide the Process of Interpretation

Years of evangelism, Bible translation, and disciple making in Pakistan influenced my development of a consistent hermeneutic—a way of faithfully interpreting the Bible without privileging one passage over another on the basis of extra-biblical standards. One incident stands out as formative. During a Bible study with new Sindhi believers, our discussion centered around Korah’s rebellion in Numbers 16. I had been uncomfortable with God’s judgment which included not only the rebellious Korah but also his entire household and relatives:

The earth opened its mouth and swallowed them and their households, and all those associated with Korah, together with their possessions. They went down alive into the realm of the dead, with everything they owned; the earth closed over them, and they perished and were gone from the community (Num 16:32-33 NIV).

One man sins and everyone related to him perishes. Where is the justice in that? I wondered. Yet, in our discussion, I discovered that my Sindhi brothers had no such reservations. In their communal orientation, identity is not grounded in the individual—my Western assumption—but in familial relationships. Korah, as the head of the family, fully represented all its members; they rose or fell on the basis of his actions. In Sindhi eyes, this outcome was not only appropriate but expected. One brother even remarked, “The reason we understand the Old Testament and you do not is that it is just like our culture!”

What I came to realize is that our engagement with—and interpretation of—Scripture always takes place within unavoidable social and cultural frameworks. Our cultural background and history shape our values and beliefs, and the assumptions and questions we bring to the text influence the meaning we draw from it. This is true not only for difficult or puzzling passages, but for every verse of Scripture. It is not just certain texts with cultural implications that are filtered through our cultural lenses, but all texts, because all texts are culturally shaped. Whether it is John 3:16, the food laws of the Torah, household instructions in the Epistles, or Paul’s prohibitions concerning women, each passage is culturally located and is engaged through our own cultural lenses. We cannot study, understand, or apply God’s Word without being immersed in and shaped by culture—like a fish in water.

This reality is not a bug or a flaw; it is a feature designed by God. Scripture does not invite us to identify abstract, absolute propositions by which to order our lives and relationships. Rather, it calls us to engage the will, character, and mission of God through our limited cultural perspectives, in order to discern how to live in faithful relationship with Jesus within our particular cultural, historical, and social contexts. Only God is absolute, and we truly encounter God only through our finite, culturally situated understandings.

Like a healthy marriage, our relationship with God through Scripture is shaped by ongoing interaction, motivated by a desire to live out faithful and life-giving expressions of love and grace. Boundaries, roles, and patterns emerge in order to protect and nurture the relationship, but they are secondary rather than foundational. No single marriage represents a universal ideal; instead, diverse, culturally shaped marriages can faithfully embody God’s design and intention for husband and wife. Therefore, it is inappropriate to impose one cultural pattern of marriage onto another context.

This same interpretive posture guides how we apply biblical commands today—not as fixed patterns to be transferred directly, but as inspired, contextually shaped expressions that reveal God’s will, character, and mission and invite discernment of faithful, culturally appropriate expressions in our own setting.

The tension between text and context becomes especially vivid for communities of faith when biblical descriptions and commands conflict with the normative values and behaviors of a particular community. Such clashes highlight a universal reality: cultural context plays a decisive role in every act of interpretation. When a biblical command or description resonates with a culture, the tendency is to identify a perceived cultural equivalent and invest it with divine authority. When it does not resonate, the tendency is to reinterpret or sidestep the text in order to accommodate prevailing cultural norms. This series of articles point towards a third option. At this stage, however, the primary aim is to underscore the influence of culture and the need to take it seriously.

In the previous article we were confronted with how cultural and linguistic constraints limit our ability to interpret Scripture. The point was not to make us despair of understanding and applying God’s word, but to help us avoid approaches to Scripture that ignore—or remain unaware of—those limitations. Now that these realities—realities ordained by God—have been brought to our attention, we can consider a framework to help us confidently engage God’s word in spite of the limitations of our context.

The proposal is that we

- Adopt a posture of both humility and confidence through a critical realist epistemology.

- Pursue truth within our limitations through three key practices:

- Reading Scripture with the expectation of encountering God,

- Engaging Scripture with sensitivity to our contextual lenses, and

- Exploring the Scriptural insights of those who live in other cultural settings.

- Welcome humble intercultural interpretation of Scripture.

A Critical Realist Epistemology

Epistemology concerns how we can know truth and reality. Because our understanding is shaped by culture, Critical Realism offers a way to pursue truth while acknowledging those limitations. It recognizes that all knowledge is mediated through particular perspectives. For Christians, this approach involves trust—confidence that God both desires and is able to reveal His character, will, and mission to those who are open to receive His revelation.

The only Absolute is God and, as human beings located in historically, socially and culturally bounded contexts, we have only relative access to God. “God is and human beings become”[1] and therefore all theology “needs to be understood in sociocultural context.”[2] Truth and reality not subject to the common conditions of human knowledge are only found in God, not in our concepts of God nor in our statements about God. Our access to the Absolute is through personal experience that is culturally shaped. Yet the Christian conviction is that it is true and significant access, because God is the Triune Creator who communicates with creation. “Total relativism destroys the possibility of meaning”[3] and the faith stance that God is and that the Absolute communicates successfully with humanity affirms the possibility of meaning.[4]

Critical Realism assumes that

- There exists a reality independent of our individual experience, a reality that is true in and of itself, whether or not we perceive it. Ultimately, this is God himself, but secondarily it is what God has created and established as the world we live in.

For example, we have a tree in our front yard and I believe the tree is there; however, the tree exists independent of my perception or belief.

- We have access to this reality (truth), through our senses and through our relationships.

I can see the tree, touch it, climb it or cut it down.

- Our access to reality is perspectival, not absolute. We experience reality through the interpretive lens shaped by our cultural and personal context. Just because perspectives are limited or incomplete does not make them incorrect. Yet any one perspective will be less than a comprehensive expression of reality.

The tree is experienced differently depending on the one engaging it. An environmentalist, logger, child, squirrel, or bird each experience the same tree differently but that does not mean their perspectives are incorrect, yet neither are they fully equivalent to the reality of what the tree is in and of itself.

In summary, Critical Realism affirms that reality exists independently of our perceptions and that we can know it truly, though always from a particular and limited perspective. It calls for humility even as it enables us to speak with confidence. We acknowledge our limitations while trusting that we can grasp real truth and express it in culturally appropriate ways.

N.T. Wright describes critical realism as “a way of describing the process of ‘knowing’ that acknowledges the reality of the thing known, as something other than the knower (hence ‘realism’), while fully acknowledging that the only access we have to this reality lies along the spiralling path of appropriate dialogue or conversation between the knower and the thing known (hence ‘critical’).”[5]

Peter Laughlin puts it this way, “A critical realist account does not claim that there is no objectivity to be had at all, but that there is no subject-less objectivity.”[6]

This culturally conditioned perspective applies both to the biblical authors conveying God’s revelation and to our own reading of the text. It also determines how we apply Scripture. All ethical values, priorities, and practices are expressed through culture. Because Scripture itself is culturally conditioned, it does not function as a universal rulebook for behaviors and ethics. Instead, we trust that its (culturally embedded) revelation is a true revelation, and that our (culturally conditioned) reading can genuinely reveal God’s will, character, and mission. With confidence in God’s faithful self-disclosure, we seek not merely to follow rules, but to conform our lives to the likeness of the Father revealed in Jesus Christ.

Three Practices to Pursue Truth within our Limitations

When we embrace a critical realist epistemology, we can identify three practices that enable proper interpretation of Scripture.

- We can read with expectation that God’s will, character and mission can be discovered through the biblical text. Engaging Scripture as revelation rests in God’s promise, “You will seek me and find me when you seek me with all your heart” (Jer 29:13).

- We can pursue a dialogical engagement between text and context that will move us towards ever increasing understanding. Because culture is our lens for engaging Scripture, we require the dynamic process of a “hermeneutical spiral” (described below) to test assumptions and find appropriate contextual expressions of kingdom living.

- We can engage believers in other times and contexts. This is the practice of exploring the wisdom and godliness of the broader community of believers throughout history and those who live in other cultural settings. Such interactions and challenges provide checks and balances for the way we live out our faith.

These three practices[7] move us towards contextually relevant Christ-centered expressions of faith and enable us “to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will” (Rom 12:2).

The first practice that we can read Scripture with expectation that “God’s will, character and mission can be discovered” will be explored in the next article, “Part 5: Developing theology through the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation,” as this is a key dynamic of the hermeneutic being proposed.

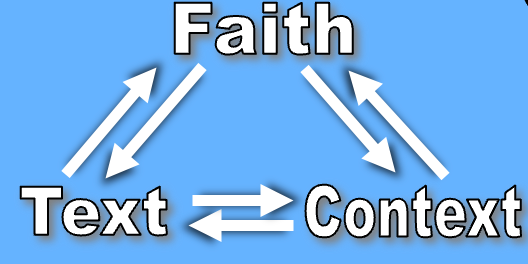

The second practice of the dialogical engagement between text and context is illustrated by the Faith-Text-Context Tension diagram:

The three corners of the faith–text–context triangle illustrate that people live in a context, and their faith (worldview, beliefs and values) is the “grid” through which they give meaning and order to that context. Text is the self-revelation of God given to us through the Bible. The reciprocating arrows between each aspect indicate the interactive dynamic or creative tension that occurs between each of the three pairs as people discuss their understanding. Tension emphasizes that while affirmation and support occur, each interaction includes both a challenge and critique that call for resolution and that shape the faith of the community.

The interaction can be expressed through D.A. Carson’s “hermeneutical spiral.”[8] The interpretation of the word of God through the text–faith and faith–context tensions is not a linear process but involves a (hopefully) upward spiral that implies an ever-increasing conformity to God’s revelation. The upward direction indicates a sincere engagement of the text that further develops a faith stance. This dynamic is not accomplished by the text alone nor by the culture alone, but by the intersection of the two as believers develop their faith. This process of dialogue “spirals with each question toward a better understanding of the salvation that comes through faith and that leads to grace and humility.”[9]

Furthermore, any adjusted faith perspective is tested for consistency and benefit within the life experiences of the community. With increasing insight into how God’s revelation speaks into the life and context of believers there is greater convergence between the meaning of the text and the outworking of that meaning in speech and behavior. This communal pursuit of God through the text and context tension is governed by God’s Spirit through the believers’ devotional posture of prayer and submission.

For the third practice of engaging believers in other times and contexts, Hiebert (The Gospel in Human Contexts, 2009. p. 29) explains the necessity and function of dialogue with others:

A critical realist epistemology differentiates between revelation and theology. The former is God-given truth; the latter is human understandings of that truth and cannot be equated fully with it. Human knowledge is always partial and schematic, and does not correspond one-to-one with reality. Our theology is our understanding of Scripture in our contexts. It may be true, but it is always partial and perspectival. It seeks to answer the questions we raise. This calls for a community-based hermeneutics in which dialogue serves to correct the biases of individuals. On the global scale, this calls for both local and global theologies. Local churches have the right to interpret and apply the gospel in their contexts, but also a responsibility to join the larger church community around the world in seeking to overcome the limited perspectives each brings, and the biases each has that might distort the gospel.[10]

Our own local theology is culturally embedded, just as everyone’s theology is—shaped by distinct cultures, histories, emphases, and languages. By engaging each another across these differences, we develop a more complete and robust theology.

The Benefit of Humble Intercultural Engagement

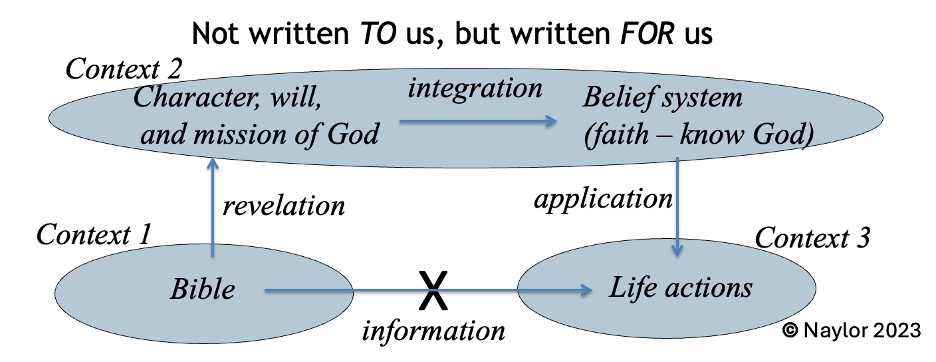

Each community of believers develops their own expressions of biblical faith through the process illustrated in the Contextually Sensitive Hermeneutic diagram provided in an earlier article:

Engaging God’s Word within a culturally embedded community is not a simple matter of applying the Bible’s “plain sense” directly (the “information” arrow). Each context necessitates a particular expression of faith, a translated rather than diffused expression.[11] The embedded cultural dimension of Scripture resonates differently within different communities, and the questions each community brings to the text inevitably give rise to diverse expressions of faith—each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

Interpretation is a complex, dialogical, and theological process that always moves through the “revelation,” “integration,” and “application” arrows of the diagram whether or not the reader of Scripture is aware of it. Because this process is mediated through cultural lenses, it results in differing priorities and emphases depending on the context. This is comparable to the tree illustration given above: different perspectives view the tree truthfully, yet differently.

This diversity of faith expressions exposes areas of weakness in our own theological orientation and challenges us to make corrections. At the same time, it can affirm culturally shaped expressions as we discern a shared pursuit of God’s will, character and mission—one that requires contextual nuance because of our particular location.

Through the Spirit’s guidance, communal discernment, dialogue with other theologies and faithful obedience, this process leads to expressions of God’s truth that maintain integrity with God’s desires and are genuinely contextualized.

In the next article we will explore how the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation guides theological development and results in robust and coherent expressions of faith.

[1] G.L. Barney, “The Challenge of Anthropology to Current Missiology,” in International Bulletin of Missionary Research 5, no. 4 (1981):174.

[2] Ibid.

[3] C. R. Taber, The World Is Too Much with Us: “Culture” in Modern Protestant Missions (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1991), 172.

[4] Mark Naylor, Mapping Theological Trajectories that Emerge in Response to a Bible Translation (DTh thesis, University of South Africa, 2013), 276.

[5] N. T. Wright, “The Challenge of Dialogue: A Partial and Preliminary Response,” in God and the Faithfulness of Paul: A Critical Examination of the Pauline Theology of N. T. Wright, ed. Christoph Heilig, J. Thomas Hewitt, and Michael F. Bird (Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016).

[6] Peter Laughlin, Jesus and the Cross: Necessity, Meaning, and the Atonement (2014), chap. 3.

[7] These three practices can be compared to and contrasted with the Wesleyan Quadrilateral of Scripture, tradition, reason and experience. All four dimensions of the quadrilateral are integrated into the three practices presented here. See T. A. Noble, “Wesleyan Quadrilateral,” in New Dictionary of Theology: Historical and Systematic, ed. Martin Davie et al. (London; Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press; InterVarsity Press, 2016), 955.

[8] D. A. Carson, “A Sketch of the Factors Determining Current Hermeneutical Debate in Cross-Cultural Contexts,” in Biblical Interpretation and the Church: The Problem of Contextualization, ed. D. A. Carson (New York: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1984), 13–15.

[9] D. Kirkpatrick, “From Biblical Text to Theological Formulation,” in Biblical Hermeneutics: A Comprehensive Introduction to Interpreting Scripture, ed. Bruce Corley, Steve Lemke, and Grant Lovejoy (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1996), 277.

[10] Paul G. Hiebert, The Gospel in Human Contexts: Anthropological Explorations for Contemporary Missions (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic), 29.

[11] This is Lamin Sanneh’s terminology. See Part 3: Why we ask “why”: The Limits of Culture and Language.