Recognizing the many influences that shape how we read and obey the Bible can make us more aware of our limitations, lead us to interpret with greater care and skill, foster a humble posture of ongoing dialogue, and help preserve our unity. All readers are invited to respond and challenge what I have written. I will be grateful for your insights and for continuing the conversation.

Some material in this article is based on my Intercultural Theology course given as an instructional lecture series with Northwest Baptist Seminary.

NOTE: Chatgpt was used for editing, but not generative purposes.

Part 5: Developing theology through the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation

After posting Part 4: A Framework to Guide the Process of Interpretation, a close friend wrote to express concern that, if the linguistic and cultural limitations I described are indeed the realities we face, then interpreting Scripture begins to feel “hopeless,” and the Bible risks becoming “a mystery and a magical goal that Christians can never hope to truly understand.” Such a conclusion, my friend warned, easily leads to a relativistic claim that “everyone’s interpretation is as good as another because nobody properly knows.” If this is the outcome, many readers will simply dismiss the argument as an overly academic complication of what is ordinarily a simple, everyday act of reading and understanding—something people do quite naturally.

Rejecting this kind of relativism, readers may instead default to their instincts, overlook cultural and linguistic limitations, and assume that their own reading of the Bible is transcultural and grounded solely in God’s universal revelation. This “realist” posture treats truth as essentially equivalent to one’s own perception of it and is often captured in the saying, “If the plain sense makes good sense, seek no other sense.”

Moreover, if this complex cultural and linguistic “veil” truly obscures God’s word, how can I then turn around and commend the Discovery Bible Study (DBS) method of reading Scripture—which I do? DBS is grounded in the perspicuity of Scripture and affirms that all people—children and adults, the literate and illiterate, believers and seekers alike—can read God’s word and understand its message.

These concerns are worth taking seriously. Because we cannot remove ourselves from the inherent limitations of language or from our cultural location, our knowledge of God, truth, and reality is necessarily perspectival rather than absolute. Yet this is not a flaw in the system, but a feature of God’s design and one that is consistent with Scripture itself. It reminds us that we are called to live by faith—that is, by trust—and not by sight. The apostle Paul speaks of seeing “as in a mirror, dimly” (1 Cor. 13:12), rather than possessing certainty grounded in proof, logical mastery, or confidence in our own capacity to know without remainder. Given that this is the reality established by God’s creative purpose, the question remains: how can we be confident that what we believe—beliefs shaped by our limited perspective—are nevertheless true? How are we rescued from the twin concerns of “hopelessness” and “relativism” that my friend raises?

Establishing faith by engaging God’s self-revelation in and through culture

The answer, I believe, emerges in this article and can be summed up in the word theology. By theology, I do not mean the weighty tomes written by spiritual giants of the past that line pastors’ shelves, but the lived reality of pursuing God. It is not primarily the abstract reasoning of trained scholars, but the daily practice of believers as they together discern what it means to follow Jesus. Theology is what we are doing whenever we reflect on our faith as we engage God’s self-revelation given through his word.

Within the Christian faith, we affirm that there is an Absolute—God—who speaks authoritatively into our lives. For evangelicals, it is the word God has spoken that guards us from chaos and relativism. God has demonstrated that he communicates sufficiently through the languages he has entrusted to us and the cultures in which he has placed us. The following seven culturally shaped ways through which God has chosen to communicate underscore this claim: our languages and contexts are not obstacles to revelation, but part of God’s design, serving as sufficient and effective means by which he makes known his will, character, and mission.

- God has communicated through the culturally shaped Old Testament revelation.

God accommodated to our human condition by revealing his nature and will through local languages and literary forms, including poetry and historical narratives that recount God’s actions in the world. This revelation employed concepts, symbols, and forms intelligible to the audiences who lived within those particular cultural contexts. - God has communicated through the culturally shaped incarnation.

God’s ultimate act of revelation and contextual accommodation is the incarnation of his Son. Within a particular human context, God revealed what it means to be truly human through the life and actions of the one who is truly God. When Jesus declared, “I am the truth” (Jn 14:6), at least part of that claim is that through him we see who God is, and through him we discover what it means to live in faithful relationship with God. This entire revelation is necessarily culturally shaped.

The incarnation cannot be understood apart from a concrete historical and cultural setting. The gospel, therefore, is neither acultural nor ahistorical. It exists—and carries meaning—only within culture and history and is communicated to other contexts through translation. Consequently, we cannot claim that there is a single, absolute, acultural theology and that our own theology represents that standard. Rather, we know absolute truth only perspectivally, within our context, and through forms that are themselves contextually shaped. Our confidence that such understanding is both meaningful and genuinely corresponds to truth rests in faith in God’s purposeful design. - God has communicated through the culturally shaped New Testament revelation

The New Testament shows us how to think about the gospel. When we ask, “What should this incarnation or this gospel look like in our setting?” we are following the pattern of the apostles themselves. The New Testament reveals the message and actions of Jesus worked out in context—truth discerned and embodied within particular cultural situations. This provides a revelation to be formed by, not a manual to replicate. We are not called to adopt the cultural practices of the New Testament world, but to faithfully work out that same gospel in our own contexts, just as the first believers did in theirs. This argument will be developed further with examples in Part 6: Biblical Support for the Proposed Hermeneutic. - God the Holy Spirit communicates in culturally shaped ways.

Scripture itself is an example. The Bible is “God-breathed” (2 Tim 3:16) into contextual forms and its prophetic message came as people were “carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Pet 1:21). Moreover, the apostles explicitly attributed many of their contextually meaningful actions to the guidance of the Spirit (e.g., Acts 16:6-7; 20:22; Gal 5:25). This testimony gives us confidence that God will successfully communicate what he intends to communicate. When Jesus promised to send a helper (Jn 14:16, 26), he was not referring to the Bible, but to the Spirit. The Spirit guides us into all truth as expressed through our lives and social situations.

When we lived in Pakistan, we observed a mystical Islamic practice in which a guru and his disciples would chant “Allah hu” (“God is one”) for hours in an attempt to enter a trance state. This is mysticism and stands in contrast to Christianity. The Spirit does not remove us from our cultural context or bypass our humanity; rather, the Spirit gives life in and through the ordinary realities of daily life. - God’s mission is contextual.

The mission of the kingdom does not depend on us. Jesus declared, “I will build my church,” and the book of Revelation proclaims the victory of the Lamb. Yet all of this unfolds within concrete cultural contexts. God’s mission is inherently contextual: we discern what God is doing in and through diverse settings. This is not an accident but God’s intention, and it confirms that God’s message can be faithfully expressed within any cultural context. - God builds our confidence through our experience in the community of faith.

Growth in understanding occurs through dialogue, shared discernment, and mutual learning—processes that are always culturally shaped. It is God’s intention that we mature together in community, learning how to express the gospel in ways that are faithful and contextually meaningful. This is what Lesslie Newbigin famously described as the “Congregation as Hermeneutic of the Gospel.”[1] - God provides culturally shaped covenants of truth and faithfulness.

A covenant involves a total commitment of self grounded in faithfulness. Vanhoozer in his book Is there meaning in this text? builds on the biblical covenant theme to argue that communication itself rests on a covenantal relationship between author and reader.[2] That is, communication is possible because the author commits to communicate truthfully, and the reader commits to listen and interpret with integrity. On this basis, understanding can occur. We therefore trust that communication is possible and have faith that God uses cultural means to communicate truthfully and effectively, accomplishing what the Spirit intends.

Theology as a journey with God

Running through all of these points is the recognition of culture’s formative influence on theology. Determining which aspects of a theology are faithful to God’s absolute truth and which are not cannot be accomplished through a purely academic or logical comparison of doctrines measured against some fixed, absolute theology—because no such universal theology is available to us. Theology is a human reflection on God’s word, and as such it is always perspectival and contextually shaped. We do not have access to a neutral or universal theological standard that stands outside culture.

Yet this is not a deficiency; it is a gift.

For a long time, I found this frustrating. Why do we rely on summarized explanations of the gospel, with a verse drawn from one passage and another verse drawn from elsewhere? Why do gospel presentations so often consist of someone explaining the gospel rather than simply letting Scripture speak for itself? Why is the Bible not “plain enough” without our additions and commentary?

That frustration arose from my own culturally shaped view of the world. In a rational, scientific framework, we ask questions, receive answers, summarize those answers clearly and logically, and then move on. Each question is meant to be resolved, closed, and left behind. But life is not meant to be so mechanical. Theology is far richer than logical summaries, and God intends us to engage in creating contextual expressions of theology rather than to have access to a single, overarching, universal system.

If that is the case, then theology is:

- A lifelong journey, not merely the accumulation of information.

- Primarily relational, focused on knowing rather than simply knowing about—relationships cannot be reduced to summaries. It’s like a piece of music, when you speed it up or take out the pauses, you lose the essence.

- A leveling of the playing field, in which no one has privileged access, everyone participates and all theology remains partial and incomplete.[3]

- Dialogical, shaped by many voices learning from one another in community.

- Multifaceted, flourishing through intercultural engagement rather than static universal claims.

Culture and theology are therefore inseparably linked in a way that actually strengthens our confidence in God’s communication. We are called to know God “in Christ” while living within our limited, perspectival contexts. Culture is not a barrier that keeps us from truth; it is the means by which we engage truth—much like glasses enable us to see clearly without ever becoming the thing we see.

We can be confident in our knowledge of truth because God has taken the initiative to speak within human contexts. Above all, Jesus Christ is the fullest revelation of the Father, and this revelation is relationally sufficient for our deepest spiritual need. As Jesus says in John 17:3, “Eternal life is to know you, the only true God, and to know Jesus Christ, the one you sent.”

By way of analogy, I truly know my wife, Karen—but not exhaustively or completely. I do not see through her eyes, hear through her ears, or think her thoughts. Yet through our shared experiences and contextually shaped relationship, I know her truly and meaningfully. That knowledge is sufficient for love, trust, and commitment. In a similar way, God’s self-revelation in the incarnation—though limited in scope—remains full, true, and profoundly sufficient. In Jesus, a finite expression of the infinite God has entered our world, revealing grace and truth in a way that meets us relationally.

How the hermeneutic of reading Scripture as revelation overcomes contextual limitations

We cannot read Scripture from a neutral standpoint, since our own cultural and linguistic location both shapes and limits our ability to understand and apply God’s Word. Consequently, approaches that directly adopt biblical patterns, commands, or promises addressed to the original audience—such as interpreting the so-called prohibition passages as straightforward restrictions on women in pastoral leadership—are likely to result in misapplication when transferred uncritically into contemporary contexts.

The hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation, or what may also be called a contextually sensitive hermeneutic, is proposed as a way of navigating this God-ordained limitation. When the telos of our engagement with Scripture is the discernment of God’s will, character, and mission, as is emphasized in Discovery Bible Study (DBS) method, we are better positioned to avoid the pitfalls that arise when interpretation remains at the level of the text’s surface meaning. Rather than seeking a “promise to claim,” a “sin to avoid,” or a “command to obey,” our goal becomes the development of a robust and coherent theology of God—one that shapes our lives and guides our expressions of what it means to be the people of God within our particular context.

Encountering the eternal God at work within cultures unlike our own, yet recognizable as the same faithful God, is the formation of theology. That theology then addresses the reader’s own life, calling forth submission, repentance, and worship. At its most basic level, engaging Scripture means reading—or hearing—and being drawn into a transforming relationship with God. This is something people can do at any stage of their spiritual journey, because it is grounded not in mastery of doctrine, but in encounter with the living God at their level of understanding.

This hermeneutic also guards against the opposite error of ignoring or filtering out passages that do not resonate with the values and beliefs of our context. All Scripture remains “useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16). Cultural dissonance is addressed not by dismissing difficult texts, but by reading Scripture as a revelation of God’s will, character, and mission rather than as a set of instructions directly addressed to us as the audience.

Finally, the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation recognizes that we never approach Scripture as blank slates. We come with theological frameworks already in place. By prioritizing the ongoing formation of our theology of God, this approach prevents us from prematurely or naïvely assuming that a command or instruction applies directly or universally. Instead, it calls us to read with awareness of our theological assumptions and cultural embeddedness, remaining open to having our theology reshaped in light of what we discover in the text.

In essence, this hermeneutic creates a dynamic dialogue between our existing theology and the biblical passage before us. We attend carefully to how the text reveals God’s will, character, and mission, and then, drawing on the broader theological understanding formed through prior study and communal reflection, we discern how to respond faithfully. Once we recognize how a passage discloses God’s purposes—and how this aligns with what we already know of God—we can live and act in contextually appropriate and obedient ways.

Conforming to theology is not the same as conforming to commands. The difference is akin to memorizing a driving rulebook versus becoming a mature, responsible driver. A mature driver understands road conditions, respects others, and adapts wisely to changing circumstances while maintaining direction and purpose. In the same way, a theology that orients our lives toward God’s mission fulfills Jesus’ purposes far more effectively than treating individual rules as fixed absolutes. Indeed, insisting on universal behaviors drawn from particular commands can undermine their intended purpose when contexts change.

Ultimately, we are called to something deeper than a religion in which acceptance is measured by obedience to commands. The Bible was not designed to function as a set of laws to follow but for relationship. It is primarily a covenantal text that draws people into right relationship with God through the Lord Jesus Christ. We are called to imitate Jesus—the living Word—and to live as beloved children of our heavenly Father. Reading Scripture as the revelation of God’s will, character, and mission provides the proper orientation that leads us to experience and live out that covenant relationship with God.

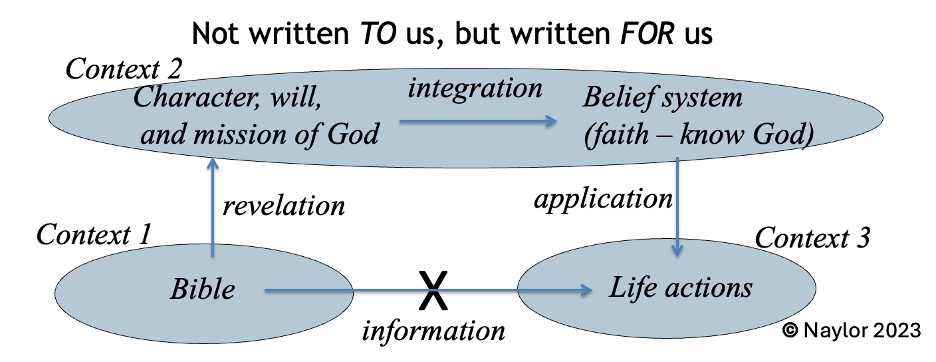

Reading the Bible to know God

As illustrated in the contextually sensitive hermeneutical diagram presented in previous articles and reproduced here, it is not possible to move directly from Scripture to application. Rather, we read biblical texts through our contextual lenses, shaped by prior assumptions. The hermeneutic proposed here offers guidance by keeping the focus of interpretation aligned with the Bible’s primary purpose: to draw us into relationship with God in Christ. It helps us navigate the dangers of unexamined cultural assumptions by framing interpretation as a process of theological and relational formation—one that seeks faithful contextual expressions of God’s revealed will, character, and mission, rather than assuming that the instructions of the text address equivalent situations in our own context.

This hermeneutic acknowledges and accommodates the interpretive lenses we bring to Scripture. It recognizes and facilitates a dialogical engagement between God’s self-revelation in the Bible and our prior theological convictions and cultural assumptions, enabling us to avoid both uncritical readings that ignore cultural dynamics and inflexibility that resists the reshaping of our theology.

Theology is, by nature, limited and human-derived—a finite attempt to comprehend God from within our particular cultural and linguistic location. We should therefore expect our understanding to be incomplete, recognizing the need for ongoing development in order to interpret any passage of Scripture in a manner consistent with God’s intent.[4] In other words, the Bible is designed to nurture in us, as God’s children, an ever-deepening sense of wonder, delight, and love for our Father.

Before we were married, Karen and I lived on opposite sides of the country. This was before the internet, and I lived for her letters. I worked in construction, and at break time I would pull her most recent letter from my pocket and read it again. Why? I already knew what it said—I had read it a dozen times! But I reread it because it made me feel close to her. I wanted to sense her presence. I wanted to connect with her.

I suggest that this is how we should read our Bible—not primarily to get answers, to improve our lives, or to find teachings to apply, but to know God. When I went to Pakistan, my role was not to teach people what they should believe about Jesus, but to expose them to Jesus. It was essential that the Bible be the curriculum, not so they could extract lessons to apply, but so they could encounter God’s love letter and see Jesus.

All biblical passages should be read as part of a larger theological movement through which we discern God’s will, character, and redemptive mission, culminating in Christ. No command, law, or teaching should be applied in isolation from this broader theological framework, since doing so allows our cultural biases and assumptions to dominate interpretation. This error is addressed through the ongoing work of theology—an ever-deepening understanding of God—cultivated by communal engagement with Scripture as the revelation of God’s will, character, and mission. Theology, then, is a creative and continuing dialogue between our faith, God’s Word, and the lived realities of our lives.

Tiers of Theology

Theologies differ according to the contexts in which they emerge. While careful theological work employs shared methodologies—such as exegesis, logical reasoning, systematic categories, and attention to biblical themes—what ultimately distinguishes one theology from another is its particular context. A failure to attend to this reality often leads people, who may otherwise be skilled in exegesis and logic, to interpret and apply New Testament patterns and commands directly to their modern context, without recognizing that faithful obedience to Scripture in different contexts necessarily requires different expressions.

Different histories, perspectives, questions, priorities, and conceptual frameworks shape how a theologian reads Scripture and seeks to understand God. The following Theologizing in Context diagram represents this dominant contextual reality that influences every theological effort. Theological methodology (the inner circle) includes both systematic theology—asking our questions of the text—and biblical theology—discerning the theology of the text. All of this work employs tools such as exegesis and logic. However, the primary point of the diagram is to illustrate that all theology is inevitably worked out using the language and assumptions of our context, the lenses by which we view reality. Even as God communicates in and through an accommodation to our particular location, so we use the contextual lenses of the our context to engage God’s word and develop our theology (experience and expressions of faith).

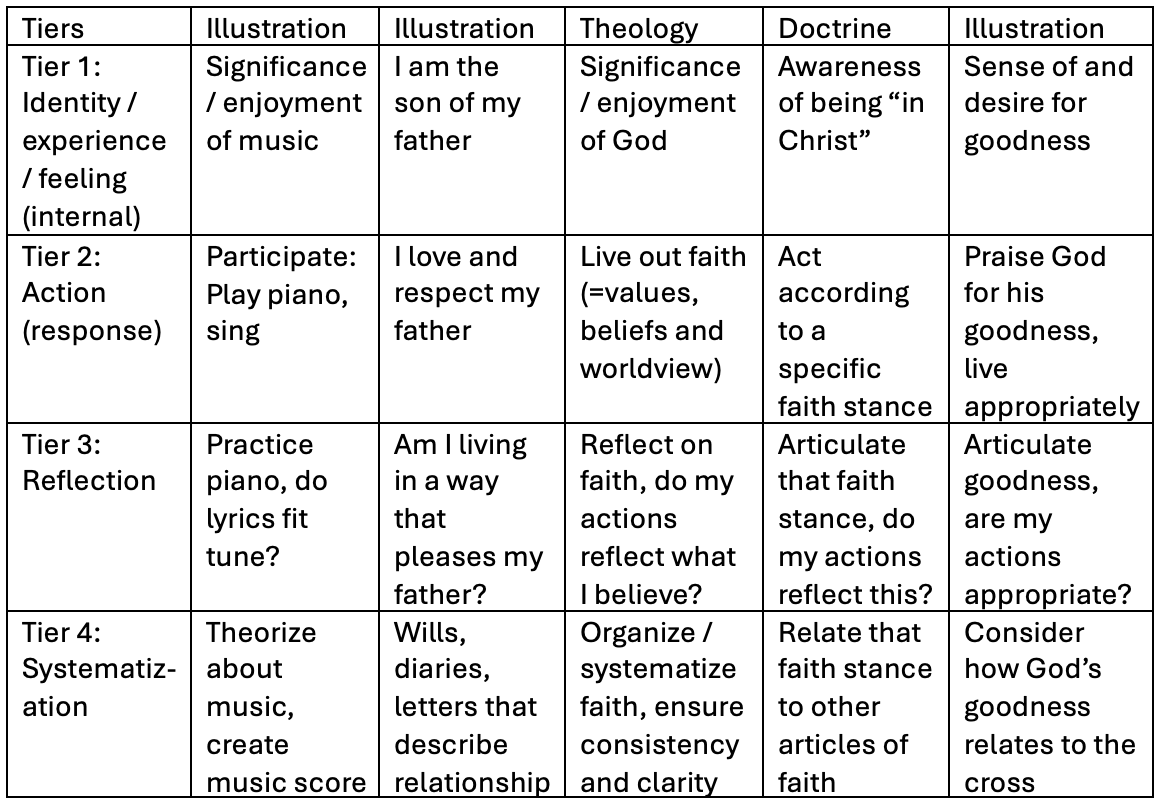

This reality does not diminish or undermine the work of theologizing. On the contrary, acknowledging the contextual dimension as an essential part of the theological process affirms that our understanding of God must be expressed within a community of believers who embody the kingdom in their particular setting. This recognition expands our view of theology beyond a purely scholarly pursuit, revealing it as a lived reality. The following chart, outlining four “tiers of theology,” helps us see how all of us are theologians as we learn to live out our beliefs.[5]

Tier 1 is the experience of reality, of identity or of knowing God.

Tier 2 is our response to that experience.

Tier 3 is a reflection on the experience or the response.

Tier 4 is the articulation of the experience, response and reflection.

The point is that tier 1 theology is where we are meant to live as Christians and is the primary motive for reading Scripture—to know God. We might read about a mother hugging her child (tier 4), reflect on the meaning of that hug (tier 3), or consider the child’s response (tier 2), but the experience of the hug itself is what truly matters (tier 1).

In the same way, when we read God’s Word, we may organize its content (tier 4), reflect on its significance for our lives (tier 3), or respond through appropriate action (tier 2). Yet it is the encounter with God (tier 1) that is central. All of these activities are legitimate expressions of theology, but we are called to prioritize tier 1: encountering God. Only through meeting God can we respond, reflect, and live out the meaning of Scripture in ways that are faithful and appropriate to our context.

Another example is recognizing that knowing about prayer is secondary to the experience of praying. George MacDonald captures this contrast well when he says, “To know a primrose is a higher thing than to know all the botany of it—just as to know Christ is an infinitely higher thing than to know all theology, all that is said about his person, or babbled about his work.”[6]

Alister McGrath helpfully describes cognitive statements or doctrinal propositions—tier 4 systematization—as a map that symbolically represents the relationships among elements of reality. Maps are valuable, but they are not the reality itself. They serve an essential function by orienting us to the world; they can be accurate in a limited sense, yet they lack the depth and immediacy of lived experience. Thus, as McGrath affirms, the purpose of doctrine (tier 4) is to guide us in reading Scripture so that we might know Jesus in our actual lives (tier 1). Doctrine is a theological map—indispensable for orientation, but never a substitute for the reality it depicts.[7]

This perspective does not dismiss or diminish tier 4 doctrine. When we are confused or disoriented, a map can help us regain our bearings. McGrath notes that doctrine “gives us a framework for making sense of the contradictions of experience.”[8] In moments of pain, loss, betrayal, or anguish, returning to the doctrinal affirmation that God is love can realign us with what God is truly doing in our lives. In this way, tier 4 doctrine becomes a lens that connects biblical truth to our lived experience.

The relevance of this discussion for considering the role of women in ecclesial leadership is that categorical restrictions on women in pastoral roles based solely on gender often reflect limited attention to both the contextual dynamics of the New Testament witness and one’s own cultural location. In constructing a systematic theology—the tier 4 “map”—such approaches may overlook the extent to which the cultural distance between the first and twenty-first centuries calls for different expressions if the biblical concerns that gave rise to the original commands are to be faithfully expressed today. Because the meaning and function of leadership are shaped by cultural assumptions and social practices, care is needed to avoid transferring one cultural pattern directly onto another in ways that do not fully reflect the author’s intention.

The view that ecclesial leadership reflects a divinely intended gender hierarchy, and therefore limits the roles of elder or pastor to men, arises from particular readings of the New Testament’s first-century concerns and from differing judgments about how Paul’s pastoral aims are to be embodied within contemporary contexts. Greater attention to both the historical setting of these texts and how the authors’ concerns can be expressed differently in the cultural realities of the present should, at the very least, foster a gracious sensitivity and tolerance for how those aims can be faithfully practiced today.

Scripture is, above all, a covenantal text that draws people into right relationship with God through the Lord Jesus Christ. Consequently, any doctrine or principle we derive from Scripture, and any application we formulate, is secondary to the primary reality of encountering the presence of God. This emphasis underscores the importance of the hermeneutic of reading the Bible as revelation as fundamentally a process of theological development—one that is centered on knowing and encountering God (tier 1).

In the next article, I will provide biblical support for this proposed hermeneutic by examining the teaching of Jesus and the apostles. Their orientation and practice challenges approaches that apply commands or instructions directly without accounting for the cultural distance between the biblical text and our contemporary context.

Footnotes:

[1] This is the title of Chapter 18 in Lesslie Newbigin’s book, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 222.

[2] Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Is There a Meaning in This Text? The Bible, the Reader, and the Morality of Literary Knowledge (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1998), 206.

[3] This is not intended to disparage the role of teachers or theological scholars. The point is simply that we are all theologians. Some of us may be far more mature and advanced in our walk with God than others, but all have access to God’s self-revelation and are invited to reflect faithfully on it within the community of faith.

[4] By “God’s intent” or “the author’s intent,” I am not suggesting access to some extra-biblical resource by which Scripture can be interpreted. Rather, the phrase refers to the text’s meaning that has been generated by the author and communicated through the written words. This meaning exists independently of any particular reader’s understanding—a critical-realist orientation. It therefore stands in contrast to purely subjective readings such as “what this means to me” or “what this means in this situation.” The language of “author’s intent” directs our attention to the text itself, inviting us to discern, as faithfully as possible, what it meant within its original context and for its original audience. That context includes attentiveness to the broader scope of the author’s writings and arguments, which together help guide our understanding of the message being communicated.

[5] This chart was inspired by Millard J. Erickson’s 3-tiered model of theology in Christian Theology. Baker Academic, 2013. Pp. 42-43.

[6] George MacDonald, “The Voice of Job,” in Unspoken Sermons, Series II (Kindle ed., 1885), 219.

[7] Alister E. McGrath, Understanding Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1990), 41–42.

[8] Ibid., 50.

Again, this article continues to breathe life into basic hermeneutics that must be heeded. Your perspective with Pakistan and numerous, simple analogies make clear the points you make, but also help the reader apply. We need more voices out there like this to educate people from a missological perspective.

Bravo, thank you for taking the time to create these articles and I hope and pray, those who are willing to learn will approach them with a soft and open heart for Jesus.

Thanks Wes, I appreciate the encouragement. I pray that people would be guided and blessed as they learn to read the Bible through a consistent hermeneutic that brings them close to God.

Thanks again for all of this Mark. I appreciate the detail and the time you take to build your ideas and argument. I am curious if you are familiar with the work NT Wright did in Scripture and the Authority of God (https://www.amazon.ca/Scripture-Authority-God-Bible-Today/dp/0062212648/). I think there are tremendous parallels between what you are saying and what he is saying. (See a summary of the book in article form here – https://biologos.org/articles/n-t-wright-on-scripture-and-the-authority-of-god). Also I really think that the work of Esther Lightcap Meek on Covenant Epistemology strengthens and supports what you are saying about the relational nature of knowing. I can point you to more of her work if you are interested.

Thanks Jeff, this is very helpful. I will take a look at NT Wright’s work on authority. Thanks for the heads up. Yes, I am aware of Esther Lightcap Meek on Covenant Epistemology and am working my way through one of her books. I appreciate your input.