Translation seeks Communication

When our main translator walked into the translation office last December in Shikarpur, Pakistan, I greeted him with, “I have a problem with heaven.” He laughed and responded, “Well, if you have trouble with heaven, what’s left? There is not much more to hope for!” I explained that it was not the concept of heaven that bothered me, but the terms used in our Sindhi Bible translation.

When our main translator walked into the translation office last December in Shikarpur, Pakistan, I greeted him with, “I have a problem with heaven.” He laughed and responded, “Well, if you have trouble with heaven, what’s left? There is not much more to hope for!” I explained that it was not the concept of heaven that bothered me, but the terms used in our Sindhi Bible translation.

Bible translators are not so much concerned with formal definitions of words as they are with how the translation is understood by the receptor audience. For example, even though the English word “heaven” can legitimately describe the physical expanse over our heads, modern translations will use more common expressions such as “sky,” thus avoiding a possible confusion with God’s abode, or the popular perception of “the place we go when we die,” i.e., Paradise. The target audience’s understanding of the translation is a key guide for the translator to ensure appropriate communication of the original message. A recent correction to the Sindhi translation of the New Testament provides an illustration.

The target audience’s understanding of the translation is a key guide for the translator

During my recent translation trip to Pakistan in Nov-Dec, 2007 we worked on the Hindu Sindhi NT translation project, which is based on the already prepared and published manuscript of the Muslim Sindhi NT. As we compared the translated texts and rechecked the meaning of the original biblical manuscripts, it became obvious that some revisions to the previously prepared Muslim Sindhi translation were also required.

Rewards after we die?

In Mt 5:12 and Lu 6:23 Jesus encourages those who are persecuted to “rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven” (TNIV). The word used in the original translation of the Sindhi New Testament was “bisht,” a word that parallels the western religious concept of Paradise. From the Muslim Sindhi reader’s point of view this would be understood as the conservative Islamic doctrine of Paradise, the place of eternal reward for the faithful received after the resurrection to life. Moreover, its use in this passage would confirm the common notion among Sindhi Muslims that we can earn rewards here on earth which will be translated into pleasures to be enjoyed in the life to come; our good deeds are tabulated and rewarded in the next life.

Sufis commonly believe that the only reward worth seeking is God himself

However, it is unlikely that Jesus intended this meaning. “Heaven,” particularly in the book Matthew, is a reference to God’s dwelling place used for the purpose of speaking indirectly about God. The phrase “the kingdom of heaven,” for example, is equivalent to “the kingdom of God” found in Luke. Both phrases refer to God’s rule over creation. To communicate this sense of “heaven” in Sindhi a different word than “bisht” is required. The phrase, “Our Father in heaven” (TNIV) in Mt 6:9, was helpful in identifying a better term. Because “heaven” in this verse cannot be confused with Paradise, the Muslim Sindhi translation has the word “Asman,” referring to the place where God resides. Understanding this meaning of “heaven” to be the same in Mt 5:12 and Lu 6:23, the Muslim Sindhi translation has been changed to “Asman” – the residence of God – from the word meaning Paradise – the place of eternal reward for the faithful. Unfortunately in Hindu Sindhi there is no equivalent term for “the place where God dwells,” and so the translation is more explicit and reads, “rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward from God.” 1

From Orthodox Islam to Mystic Sufism

This change of a single word represents a significant theological shift for the Sindhi reader: away from the concept of earning rewards that will be received after death, to a desire to please God and make him the appropriate focus of our concern when enduring suffering on earth. As a result the new translation will resonate with many Sindhi people as affirming the teaching of the mystic Sufis, who are greatly revered in the Sindh. Sufis commonly believe that the only reward worth seeking is God himself. A popular Sufi saying is, “If God is in heaven (bisht), then I want to go to heaven. If God is in hell then I want to go to hell.”

The following Sufi story also illustrates this understanding:

A religious leader was preaching to his students in the presence of a Dervish: "If you do bad things you will go to hell. If you do good things you will go to Heaven (bisht). So do good and not evil so that you will go to Heaven and not hell."

The Dervish on hearing this arose and went into his house. There he wrapped one end of a stick with cloth, set it alight and began to walk through the town.

"What are you doing?" people asked.

"I’m looking for Heaven and hell", he replied, "And when I find them I will burn them both to the ground."

"That is absurd," they cried. "Why would you want to do that?"

"Because I have just heard religious instruction that teaches people to do good out of fear and selfishness and not for the sake of knowing God. It would be better if those causes of greed and terror were removed so that people would only seek God for Himself and not for their own gain!" 2

Bridges for the Truth of God’s Word

But is there not a third possibility? Must the Sindhi translation of “heaven” recall a conservative Islamic theology on the one hand or mystic Sufi teaching on the other? Is there no “neutral,” non religious terminology that can be used to convey the biblical concept of heaven? The answer is “No.” By definition, the act of translation uses terminology and concepts already in use by the receptor audience, otherwise communication will not occur. It is essential in Bible translation to ensure that the terminology used provides an equivalent meaning that is faithful to the original text. The similarity between the meaning of the concept in the original manuscripts and the Sindhi understanding makes communication possible, while the differences can hopefully be overcome by reflecting on the meaning of the word within the greater context of scripture.

Moreover, when pre-existing teaching within the Sindhi community parallels biblical teaching, it is a cause for rejoicing. Not only is the task of translation made easier, but such teaching acts a bridge for the truth of God’s word. When Sufi teaching is assumed true by the Sindhi reader and similar teaching is encountered in the New Testament, the result is an affirmation of the truth of God’s word and encouragement to trust the NT.

Moreover, when pre-existing teaching within the Sindhi community parallels biblical teaching, it is a cause for rejoicing. Not only is the task of translation made easier, but such teaching acts a bridge for the truth of God’s word. When Sufi teaching is assumed true by the Sindhi reader and similar teaching is encountered in the New Testament, the result is an affirmation of the truth of God’s word and encouragement to trust the NT.

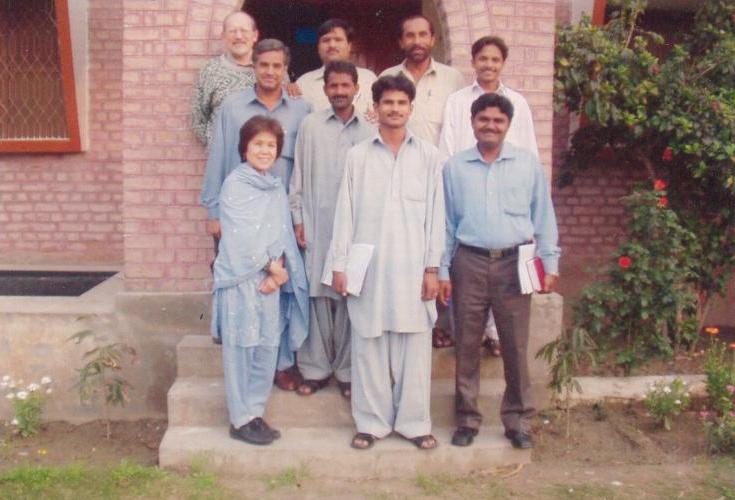

(The photo is of our Hindu Sindhi workshop participants, March 2006)