Reprinted by permission from NIMER

NIMER: Northwest Institute for Ministry Education Research

Introduction

During my years as an evangelist and church planter among an unreached people group (1985-99), I struggled because of misconceptions I had about my role as church planter, my vision of church, the meaning of disciple making, and the activities I needed to be involved in to plant a church. My failure to accomplish what I had hoped resulted in a period of reflection and research as I interacted with missiologists and learned from mission practitioners who have experienced a moving of God’s Spirit in their ministry. My theological development has led me to embrace Disciple-Making Movements (DMMs) as one effective way God is using to bring about his kingdom in this world.

Embracing a phenomenon as a movement of God requires theological justification. This article seeks to sketch a way forward, or at least stimulate current dialogue, by following D Bosch (1980 and 1991) and CJH Wright (2006) in their focus on the missio Dei, the mission of God, and suggesting that the missio Dei serves as an appropriate and adequate theological framework and hermeneutic to justify the methodological emphases of DMM principles and practices. It argues that DMMs are appropriately grounded in a dialogical process between the biblical text and context – an ongoing missional praxis[1] – that reflects the priorities and purposes of God’s mission revealed in the Bible. As such, this article is more metatheological[2] than theological by considering how DMM functions within a missio Dei framework than by providing theological conclusions.

Following a brief overview of Disciple Making Movements and DMM principles, a proposal of how the missio Dei can function as a hermeneutic to address theological questions and concerns about DMM is presented. Three questions about DMM are then explored using the missio Dei lens:

- Is the DMM approach of deducing effective methodologies from successful movements consistent with the missio Dei?

- Is the form of church that results from DMM principles and practices an appropriate expression of the missio Dei?

- Is the practice of welcoming nonbelievers into a discipleship journey consistent with the missio Dei?

The Phenomenon and Methodology of Disciple Making Movements

The modern phenomenon of rapidly multiplying Disciple Making Movements (DMM) in Christian missions was brought to the attention of missiologists and missions practitioners in the 1990s through the work of David Garrison[3] and others who observed “streams of multiplying churches within ethnolinguistic people groups” (Slack 2011). The name given to the phenomenon was originally “Church Planting Movements” (CPM), out of which emerged the strategy and model of Disciple Making Movements (DMM) that leads to a CPM[4]. DMMs have continued to grow with a reported 1,369[5] movements by the end of 2020, up from approximately 600 movements in 2017 (Long 2020). The measure used to consider a response to Jesus in a people group as a “movement” is when, within a few years[6], a minimum of

four generations of disciples [have] gathered in churches, in multiple streams. Although not every movement has a minimum measure of total disciples, most use the 1,000 disciple minimum. Even if they don’t use that measure, four generations in multiple streams means a movement would normally be close to or greater than 1,000 disciples. Counting this way, we know of 1,369 movements…. [Once] a movement reaches four generations, it rarely ends.

Currently, “at least 77 million disciples in 4.8 million churches” have been “documented”[7] in these movements (Long 2020).

The change in focus from church planting (CPM) to disciple making (DMM) shifts the attention from the end result of the phenomenon – churches – to the means that drives the movement – disciple making. This shift also represents a change of focus from an observed work of God, since Jesus claimed the power and authority to “build his church” (Mt 16:18), to the efforts of believers who are commanded to “go and make disciples of all nations” (Mt 28:19 NIV). In an article outlining a history of CPM/DMM, Moran (2021) states that while Garrison’s CPM label described the result, others

preferred to describe the process – disciple making. Multiplying churches was the result. It is not clear who first said, “When you make disciples, you always get churches, but when you plant churches you don’t always get disciples’” but this phrase brings clarity to the two terms, start with making disciples, and you get churches.

Watson & Watson (2014), and Trousdale & Sunshine (2018), among others, have outlined characteristics and practices of DMM practitioners. At the heart of DMM are the DMM principles and practices[8], which are being adopted by missions practitioners, including the missions agency I am connected to, Fellowship International, with the desire to replicate such movements in people groups around the world. The “principles” are promoted as foundational commitments by which we join God in his redemptive mission. The “practices” are adopted and lived out in order to make disciples, resulting in multiplying movements[9]. The strong pragmatic and methodological framing of this approach to ministry calls for theological reflection[10]. The missio Dei is proposed as an appropriate theological framework sufficient to embrace a DMM methodology.

The missio Dei as a theological framework and a hermeneutic

Missio Dei or the mission of God is the greater reality within which the biblical story unfolds (Bosch 1981, 75-83) and functions as a hermeneutic that interprets the Bible through the lens of Jesus as the redeemer of the world. CJH Wright (2006, 41) refers to this as the “missional story… that flows from the mind and purpose of God in all the scriptures for all the nations. That is a missional hermeneutic of the whole Bible.” If we define missions as the role and responsibility of the people of God in fulfilling the Great Commission (Mt 28:18-20)[11], then the mission of God – the missio Dei – for the world is the source and framework for missional activity of the church. The Father sends the Son (Jn 17:8) and the Son sends his followers to join in the mission (Jn 20:21), but at no time is the primary role of God as the missionary God displaced. The coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost is not “passing the baton” to the apostles, but rather an affirmation of the believers’ role in God’s mission and the sign that Jesus was in them and working through them. The “resurrection of the Messiah means that Jesus’ exaltation has resulted in, not the displacement of the primacy of God’s mission, but the continuation and expansion of that mission through the ‘pouring out’ of the Holy Spirit upon God’s people (Acts 2:33)” (Naylor 2013, 242). God is revealed in Jesus as redeemer, the Holy Spirit draws believers into that mission, and the outworking of that salvation is the experience of God’s kingdom through God’s people (i.e. local expressions of the church).

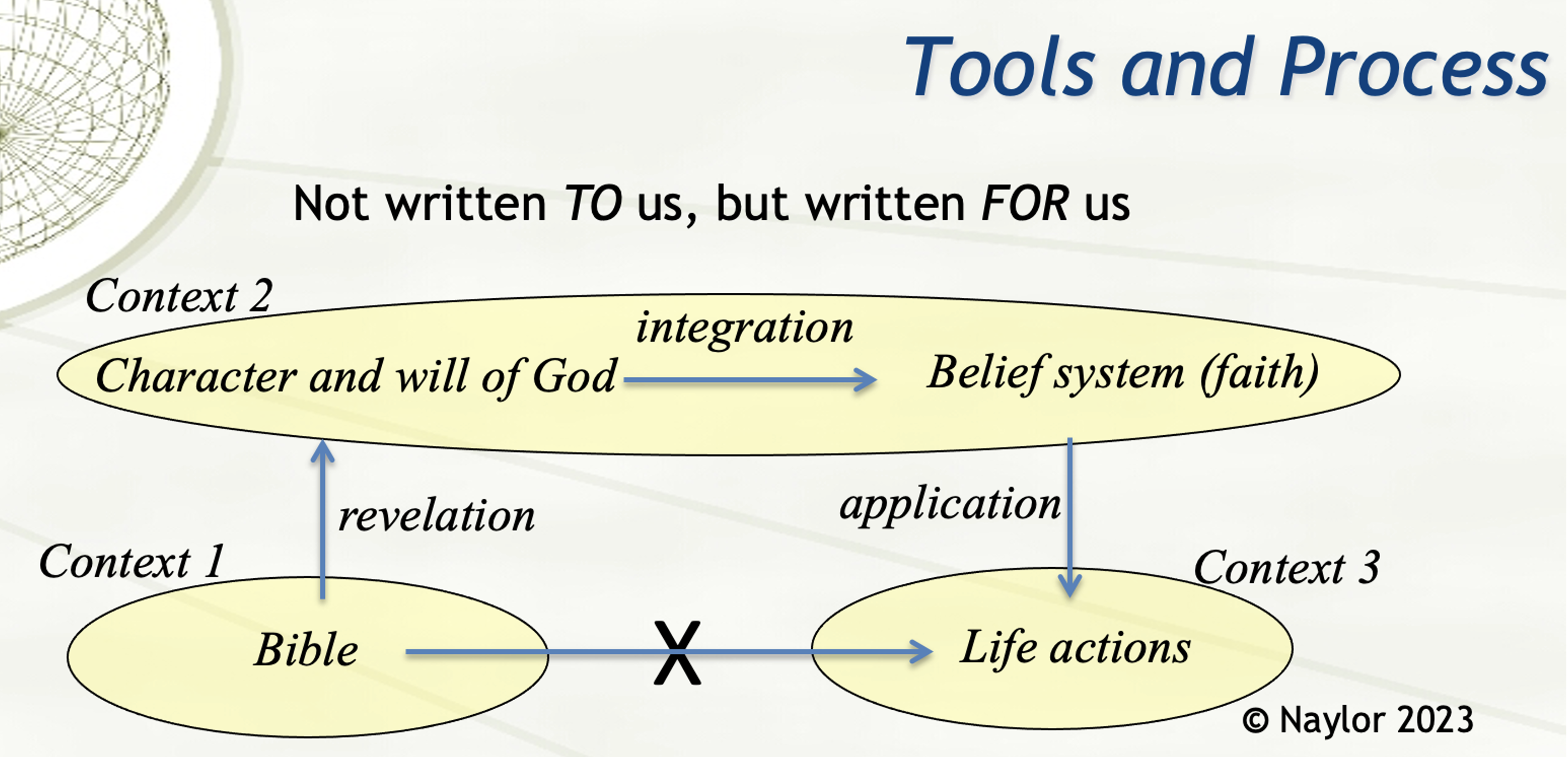

An important corollary of the missio Dei hermeneutic is the recognition that the Bible is not to be read as a manual or guidebook for our lives in the sense of directly addressing the questions of our time. Instead, the Bible is approached as a revelation of God: God reveals his character, will, and mission within a variety of contexts and historical events. From that revelation, believers develop a theology of who God is and what God desires for his people. That understanding is then translated into relevant words and concomitant actions for each context and generation. Believers are called as a community to be “the hermeneutic of the gospel” (Newbigin 1989, 222) as they work out what it means to express and advance God’s kingdom in their setting. In particular, the events in the book of Acts and the instructions and encouragements found in the epistles are viewed as examples of a methodology for contextualizing and advancing the gospel. Rather than handbooks given to resolve the questions for the church today, these writings are a model for how those questions are to be addressed. For example, the New Testament (NT) does not provide a church pattern or form that is to be replicated throughout the centuries regardless of the context. Rather, we have an example and model of how “church” was envisioned and worked out within a particular setting as the apostles grappled with the implications of the gospel. Our response is not to assume that the apostles worked out how to express gospel, church and ministry for our setting so that we need only mimic the pattern and model. Instead, we are called to embrace and engage in a process similar to what they modeled, wrestling with gospel, church, and ministry within our settings through a missional praxis that maintains a creative tension between text and context resulting in contextualized patterns and models that express and advance the kingdom of God. God’s revealed word, the gospel and the nature and desire of God remain the same, it is our context that needs to be freshly engaged. We follow in the steps of the apostles as we find suitable expressions of gospel, church, and ministry for the world we live in.

This hermeneutic is the basis for the following arguments. Verses are not quoted with the assumption that the biblical text directly supports and outlines a DMM methodology. Rather, the claim is that the biblical text is a revelation of God and God’s mission to the world; the DMM principles and practices are examined within the light of that theology. Validation of DMM principles and practices is not found through a direct correlation with NT practices, but through correspondence with the missio Dei as revealed through the writings of the apostles.

This approach may appear to contradict DMM practitioners who claim that DMM principles and practices are a restoration of NT practices and Jesus’ commands concerning how we are to advance the kingdom. For example, Chad Vegas (2018) condemns the assertion of DMM practitioners who believe that they have “restored the proper biblical understanding of missions methodology that has been lost for nearly 1600 years.” He quotes Trousdale (2012, 16) as saying “All the principles that we are seeing at work are clearly outlined – indeed, commanded – in the pages of Scripture” and “…we have seen the Disciple Making Movement ministry model before, especially in the Gospels and the book of Acts … actually throughout the Bible.” (38). Vegas quotes Paul and David Watson (2014, 26) who say, “The DMM is about doing what was done in the first century….” Vegas reads this as a claim that DMM is a move back to Jesus’ or the NT methodology which gives it divine authority and implies a rejection of methods that have not had the same claims of fruitfulness.

I suggest that the reality is that these practitioners have not recovered principles lost to the church, but rather they, along with others throughout Christian history, have re-discovered missional principles that appropriately conform to the missio Dei. Following in the footsteps of those with apostolic calling throughout the centuries, they have begun to apply principles that are needed to shape missions endeavors for our time. Rather than an expression of arrogance, it is an expression of humility and submission to the demands of the missio Dei. These principles are not patterns drawn from NT practices that others may have missed or ignored; they are reflections on the missio Dei that answer the call to join Jesus in his mission and discover what that should look like within our time and context. The fruit is evidence of God’s blessing on that dedicated pursuit.

With that orientation to a missio Dei hermeneutic in mind, the three questions proposed earlier are now addressed.

Theological question 1: Is the approach of deducing effective methodologies from successful movements consistent with the missio Dei?

Evidence for the DMM phenomenon is strong because of the communication and documentation that is possible today. However, the connection of the phenomenon to DMM methodology requires reflection. Is the phenomenon due to the methodology, or are these practices just coincidental? Perhaps the results are more related to the character and passion of the dedicated practitioner than a particular methodology (Prinz & Coles 2021). Maybe these movements are a sign that God is at work and calling those people to himself, rather than evidence for human agency and insight. It could also be that these movements are due to contextual distinctives that are conducive to such movements. After all, if these DMM principles and practices are God’s prescribed method for reaching the world, should not the phenomenon be global? Currently there are few, if any, movements in the global north; DMMs are primarily occurring among people groups that are communally oriented rather than individualistic and among groups that have respect for sacred texts (such as Muslims). Some have evaluated the methodology and claim it is heretical (Vegas 2018) or just a fad (Stiles 2020)[12].

Each of these questions requires separate consideration beyond the scope of this article; what is proposed here is that the missio Dei provides an appropriate theological framework to view the methodologies associated with DMM as activities through which a practitioner joins with God as the Spirit creates a disciple-making movement. Allen (2011, 87) states that such practices “are a benchmark of applied wisdom, not an exhaustive catalog of formulas. They are descriptive, not prescriptive, they are correlative, not causative. They do not replace the ‘God factor,’ and are not necessarily universal in scope.” The wording used by Allen[13] reflects the tension felt by practitioners who are focused on making disciples and disciple makers, while affirming that it is God who brings about essential spiritual growth and multiplication. How can methodology be associated with the work of the Holy Spirit without undermining the freedom of the Spirit to move where he pleases (Jn 3:8) or claiming too much control for human actions?

It is simplistic to assume that DMM practitioners first discovered impacting practices from Scripture and then applied them resulting in the observed phenomenon. Neither would it be correct to assume that such multiplying disciple-making movements appeared on their own without the intervention of human agents, as if it was only from observing existing movements that appropriate practices were deduced. Instead, as with all successful ministries, it is more reasonable to suppose there were periods of setbacks and failures as dedicated workers sought to creatively work out the tension between text and context in an effort to discern how to participate in Jesus’ redemptive work by stimulating disciple making movements. Indeed, DMM practitioners have insisted that they had many difficult and unfruitful years before the blessing of a DMM[14]. It is an ongoing pattern in missions that missionaries take up the mantle of John the Baptist and seek to “Prepare the way for the Lord [and] make straight paths for him” (Mk 1:3 NIV). The power is in the Holy Spirit who changes people’s hearts; the labor is in the perseverance of those called to an apostolic ministry of preaching the good news. The emergence of such movements is evidence of the Spirit of God coming along the prepared paths.

The pattern of the missio Dei is a merging of human labor and the empowering of the Spirit; the God- and human- dimensions integrated for the purpose of redemption in this world. Dedicated missionaries seek contextually sensitive pathways to communicate the relevance of the gospel so that it resonates with people and they begin to follow Jesus. This human dedication and action is not separate from the work of the Holy Spirit, but evidence of the Spirit at work in and through those God has chosen and called. It is important to avoid a false dichotomy between the work of the Holy Spirit and the human initiated means of missions. A recognition of the impact and cause of human effort goes back at least to the father of modern missions, Wm Carey, whose famous thesis, “An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians, to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens (1792)” (Anderson 1998) insists that human means do facilitate change. The determination of God to use his people to reach others is consistent throughout Scripture. When God calls a prophet, that person is called to be the voice of God (e.g., Jer 1.9). God delivers his people from Egypt through the hand of Moses, and the voice of Aaron (Exo 4.15-17), as one example among many.

The incarnation and work of Jesus is the climatic movement of the missio Dei. All God did previously pointed to Jesus (Lu 24:25-27). The Word of God revealed as a human being did not diminish the role of people in fulfilling God’s purposes, but rather brought believers to a greater involvement in God’s redemptive work. Jesus’ statement, “I no longer call you servants, because a servant does not know his master’s business. Instead, I have called you friends, for everything that I learned from my Father I have made known to you” (Jn 15:15 NIV), welcomes his disciples into the mission of God. With the coming of the Holy Spirit, the apostles became empowered for God’s work. What they then did to exhort people to enter the kingdom was not just coincidental to the work of the Holy Spirit, but impacting and effective expressions of the Holy Spirit’s power. The lesson is that it is futile and artificial to define a division between the work of the Holy Spirit and human efforts. God chooses people to be his means of breaking into the world. To try to discern where people’s labor ends and God’s begins is as impossible as seeking to distinguish language from speech. The message is Jesus, the power is the Spirit, the kingdom is God’s; the means by which God advances his mission is the actions of his people.

In parallel to the argument that the moving of God’s Spirit is distinct but indivisible from the labor of God’s people in the missio Dei, consider that the word for spirit in Greek, pneuma, and in Hebrew, ruach, is the same word for wind and breath. God breathed into Adam the breath of life (Gen 2.7). Our breath is our spirit. Remove our breath and our spirit departs. This does not mean that spirit and breath are identical; they are distinct but indivisible. The spirit is our life, which cannot be reduced to the air that moves in and out of our lungs. Yet, the act of breathing is a key experience of the spirit of life granted to us. So it is with God’s Spirit working through God’s people, distinct but indivisible.

When we see God at work because people are coming to Jesus and being obedient to his call on their life, then the methodology used is validated as a pathway that prepares the coming of the Holy Spirit. To deny God’s hand in such a result would open us up to the rebuke that Jesus gave to the Pharisees when they refused to see the hand of God in Jesus’ miracles. Jesus called their attitude a “blasphemy against the Holy Spirit” (Mt 12:31 NIV). It is not merely justified, but crucial that the fruitful practices through which God is drawing people to himself be identified, adopted and multiplied. These are the means of missions and the actions through which the Holy Spirit is bringing people to repentance and redemption.

“By their fruit you will recognize them” (Mt 7.16 NIV) refers to the character and actions of those who truly follow Jesus. But the principle also holds for discerning methodologies. When the “fruit” is multiplication of disciple makers who are living out kingdom values, such methodology is worth emulating. This is not pragmatism or a guarantee of success; without the moving of God’s Spirit, there will be no spiritual fruit. It is the acknowledgement that there is a pathway that God has used, a “straight road” along which the Spirit has moved. To adopt such pathways is an act of humility before God, an act of prayer, that God will bless equivalent practices in a new setting. The practice of DMM to discover fruitful practices is an appropriate and necessary response to join Jesus in the missio Dei.

At the same time, such methodologies cannot be plucked out of one context, analyzed abstractly and then plugged into another context in a mechanistic fashion. Discovering impacting practices that result in fruit is not a call to uniform transference, but to translation, using Sanneh’s (2015) terminology. That is, a missional praxis of action coupled with reflection is required, one that pursues the contextualization of gospel, ministry, and church within a particular setting so that fresh and resonating expressions are discovered by insiders as they encounter God through his word. Missional praxis requires an ongoing evaluation of the applied methodologies to determine if the “fruit” does reflect the missio Dei. The remaining theological questions are an attempt to engage in such reflections on two of the more contentious issues.

Theological question 2: Is the form of church that results from DMM principles and practices an appropriate expression of the missio Dei?

DMM principles and practices challenge traditionally and historically assumed patterns of missions and church planting. One DMM emphasis is multiplication and reproducibility. The descriptor “rapidly” in “rapidly multiplying movements” (Trousdale & Sunshine 2018, 201) is not an incidental characteristic of DMMs, but a key outcome. Whatever does not promote the “rapid” advancement of more groups of disciple-making disciples is discarded. If the method cannot be easily reproduced by new believers, it is rejected. This approach creates relational and ecclesiastical tensions. How can the goal of multiplication be maintained without reducing ministry to an algorithm or compromising the essential inter-relational nature of engaging people with love and compassion? How does the commitment to “rapid multiplication” recognize and allow for the time required for a disciple to mature and become fit for leadership? How does this emphasis on growth, change, and expansion accommodate the need for Christ-centered communities to provide stability for families and sustenance for the suffering?

“Rapid,” in “rapidly multiplying movements,” is not a description of short-term tactics used by DMM practitioners to achieve quick results. In fact, workers commit to the slow process of developing relationships in order discover those in whom God’s Spirit is working so they can disciple them towards obedience to Jesus. “Rapid” refers to the exponential result – disciples become disciple makers who, by following DMM principles and practices, continue to promote the gospel so that others become obedient disciples and disciple makers (cf. 2 Tim 2:2). The reality is not that there are tactics that speed up the process, but that there are strategies that create disciple makers. As these disciple makers multiply through the same slow process that began the movement, there is the appearance of a rapid movement because of the exponential growth of disciples. This pattern is seen in the epistles of the apostle Paul, who labored with much opposition, often with little fruit. Nonetheless, his persistence in advancing the gospel (Php 1:12-14) was repeated with multiplying effect in some areas, such as among believers in Thessalonica, so that Paul called them a “model to all believers in Macedonia and Achaia [because] the Lord’s message rang out from [them, and their] faith in God has become known everywhere” (1 Thess 1:7-8). This movement of an exponentially growing number of disciple makers is a valid expression of the missio Dei and follows naturally from Jesus’ vision for the gospel to reach to “the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8), as well as from the vision of multitudes who will stand before the throne (Rev 7:9)[15].

With this orientation, “rapid” does not indicate a lack of depth, but its opposite. The conviction is that obedient disciples committed to Jesus’ mission will look for those in whom God’s Spirit is at work and challenge them to obey the call and conform their lives to the will and nature of God. With DMM, depth is developed through obedience and commitment to Jesus’ mission since disciple making is the first priority. Such obedience is less about holding right opinions or obeying specific commands, and more about a journey with others learning how to conform to the image of God in everyday life. That is, biblical commands are recognized as context specific; the goal, therefore, is not to obey commands given to others in a different time and place, but to use them as a lens to discover the desire and nature of God. Becoming a disciple is about learning together how to be children of the Father of the Lord Jesus Christ. Obedience is more than doing what he says, it involves being like him. The biblical text reveals the Father’s will and nature. This gets to the heart of the missio Dei: the redemption of the world is to be “in Christ,” so that we can live in community together as images of God, little icons that bring others into God’s presence. The missio Dei vision is that God’s people become the church of God with a missional purpose for the redemption of others.

There is no rigid dichotomy[16] at play when comparing DMM to traditional or conventional assumptions about how churches are to be established. There is a different emphasis, but this does not necessarily imply a negative judgment upon the orientation another group may have towards their ministry. The goal of DMM is narrow: rapid multiplication of groups of disciples who are an expression of the church of Jesus Christ. This goal requires an intentional strategy which distinguishes it from the methodology of conventional church planting efforts[17]. Consider these contrasts that reveal a different focus, but are not necessarily incompatible:

- Conventional church emphasizes depth – establishing believers in their faith, while DMM focuses on breadth – seeking the expansion of the kingdom through a multiplication of disciples.

- Conventional church focuses on correct doctrine – establishment of an agreed faith declaration as a basis for unity, cooperation, and expansion, while DMM views a commitment to obey Jesus as the sole basis for fellowship, maturity and reproducing groups.

- Conventional church seeks an expression of God’s people visually, institutionally, and permanently established within the broader community – a process requiring a large investment of resources, while DMM establishes small, flexible groups with obedience to Jesus as their central creed and activity – low visibility, non-institutional, and relationally oriented groups.

- Conventional church follows forms and patterns that provide stability and conforms to established expectations, while DMM groups have a functional orientation to being the body of Christ that narrowly focuses on obedient discipleship.

- Conventional church prioritizes worship services attended by congregations with appointed leaders preaching and teaching, DMM arranges small groups of people who gather around God’s word to discover, communally and individually, what they are called to obey.

- Conventional church locates authority in mature and established leaders, while DMM practitioners empower even new believers to facilitate group disciple making.

- Conventional church develops a few leaders through an educational process that may take years before candidates are considered prepared and sufficiently educated to lead, while in DMM disciples are challenged and supported to invest in others early in their spiritual journey.

A key strategy in DMM methodology is Discovery Bible Study (DBS) through which a group of interested people are not taught, but guided through a series of questions to discover for themselves the will and nature of God in a passage of Scripture[18]. Quoted in Cocanower & Mordomo (2020, 75-76), George Terry suggests that this approach may be a reaction to the passivity seen in some believers who rely on experts to explain the text. Some assume that the Bible cannot be understood without the guidance of those who are dedicated to the study of God’s word. In contrast, the facilitated discovery process, a priority in DMM, (1) motivates disciples to personally engage and understand God’s word for themselves, (2) guides them to read God’s word as a revelation of God’s nature and will, (3) challenges them to conform their lives to what they have learned (obedience), and (4) ensures a reproducible disciple-making methodology through a set of simple but profound questions. Farah (2020) adds, referencing Dyrness’ work (2016), that this inductive approach to mission bypasses the contextualization step in which an outsider attempts to formulate a resonating message of the gospel, and instead relies “on God’s active presence within new contexts as hermeneutical spaces for people to work out what the Bible says to their situation in ways they understand.” This direct engagement of God’s word that avoids the mediating human teacher challenges people to attend directly to God’s word – “thus says the LORD” – and, by doing so, is bearing fruit.

The approach of DMM, as is evident from DBS, is to avoid imposing an external form of church while emphasizing the function and purpose of church as a Christ-centered community. By practicing key elements[19] of being the body of Christ, focused on obedience-based discipleship, the group together develops a contextualized expression of their growing faith. By keeping the theology of the will and nature of God front and center[20] as they conform their lives to Jesus, the group learns how to be the church. This is not an idealistic vision suggesting that such groups will not have the disagreements, divisions and struggles prevalent in other church settings, but the process encourages them to face those challenges from an posture of obedience to Christ.

At the same time, the DMM methodology should not be an excuse to reject the many resources that God gives to advance his kingdom and guide his church[21]. Teachers and prophets, Christian traditions, and historical interpretations also play an important part, as well as the “communion of saints” through which Christians engage the studies and meditations of godly men and women throughout the centuries and around the world. Nonetheless, the priority in DBS is to establish the discipline of attending to God’s word directly and from that posture engage the broader community of believers.

Theological question 3: Is the practice of welcoming nonbelievers into a discipleship journey consistent with the missio Dei?

Including nonbelievers as disciples in the disciple-making process has soteriological implications. Rather than maintaining a sharp distinction between evangelism to nonbelievers and disciple making with believers, DMM incorporates evangelism into the disciple-making process by discipling people before they become fully committed followers of Jesus[22]. The DMM position is that leading people to obedience is equivalent to leading them to faith (cf. Jas 2:17). To choose to obey God and live to please him is an act of faith. Here obedience is understood not as compliance to biblical commands, but the act of trust, submission and conformity to the revelation of the character and will of God as revealed in Scripture. It is the response to Jesus’ call to “repent” and “follow me” (Mk 1:17 NIV).

DMM practitioners have observed a process through which people grow towards a covenantal relationship with God through a gradual increase in understanding, commitment and action. Through the DBS method, which is ideally done in a group setting, all are immediately confronted with God’s words and challenged to commit to a path of obedience at the level of their comprehension, conviction, and belief. This is one step in a journey of faith that establishes a consistent expectation and pattern of following Jesus, a pattern maintained both before and after their expression of full commitment to Jesus, thus affirming the maxim, “what you win them with, is what you win them to.” An analogy of courtship is instructive; a couple meets, develops a relationship, becomes engaged, and then commits their lives together in a marriage ceremony. The entire process consists of ever increasing levels of understanding and commitment, culminating in a covenant[23]. In the walk of the disciple, the covenant of faith is expressed through baptism, with the Lord’s Supper acting as the ongoing reminder of that covenant.

The priority communicated through the discovery process is “Begin to follow Jesus and see where the journey takes you.” Throughout the NT we see such a progression as the apostles grow in their understanding of and commitment to Jesus. They hope Jesus is the Messiah, but they do not know what that means and often misunderstand. But as long as they maintain their commitment to Jesus (Judas did not, many other followers also turned away – Jn 6:66), they will continue to learn how to walk in the way of Jesus and experience the power of the resurrection and the filling of the Holy Spirit. Because “many are called [and] few are chosen,” (Mt 22:14 NIV), it is not our place to know who is chosen. It is the role of disciple makers to invite all to follow Jesus. That orientation to follow begins with the seeker’s first response and continues consistently throughout a disciple’s life.

The journey towards Jesus begins with an invitation, rather than covenant. It is a paradigm of a centered faith that looks to obedience as the key indicator of faith, rather than a bounded faith that requires adherence to particular doctrines for acceptance[24]. This orientation is a form of relational theology, a commitment to the person of Jesus, rather than a declaration of beliefs about Jesus, and as such it reflects the heart of the missio Dei: The mission is God’s mission. It is Jesus who builds the church. It is the Holy Spirit who convicts people of sin and chooses them to become children of God. Our role as disciple makers is to give the invitation to know “the only true God, and [know] Jesus Christ” (Jn 17:3) and lead those interested into a confrontation with God’s word – a word “alive and active [and] sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart” (Heb 4:12 NIV).

Conclusion

DMM is one exciting and impacting way through which God is working out his mission in the world. In proposing the missio Dei as the theological framework and hermeneutic that validates DMM, this article is a limited beginning and does not develop a theology so much as describe a theological process that invites further conversation and challenge. Nonetheless, by identifying theological assumptions observed in the DMM phenomenon that reflect the missio Dei, there is the promise of that a DMM practitioner truly joins Jesus in his mission. While the missio Dei is a helpful framework and hermeneutic by which to comprehend this moving of God’s Spirit in the advancement of the Kingdom, there is much more that needs to be considered.

Soli Deo gloria.

References

Allen, D. 2011. “Eyes to See, Ears to Hear” in From Seed to Fruit: Global Trends, Fruitful Practices, and Emerging Issues among Muslims. Edited by J. Dudley Woodberry, 79-90. Pasadena: Wm Carey.

Anderson, G. H. 1998. “Carey, William (1761-1834): English Baptist Bible translator, pastor, and father of the Serampore mission” Available online at https://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/c-d/carey-william-1761-1834/.

Bradshaw, B 1993. Bridging the Gap: Evangelism, Development and Shalom. Monrovia: MARC.

Bosch, DJ 1980. Witness to the world: the Christian mission in theological perspective. Atlanta: John Knox Press.

_________1991. Transforming Mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission. Maryknoll: Orbis.

Cocanower,B & Mordomo J. 2020. Terranova: A Phenomenological Study of Kingdom Movement Work among Asylum Seekers in the Global North. Self published.

Coles, D & Parks, S. 2019. 24:14 A Testimony to All Peoples. Spring, Texas: 24:14.

Dale, T., Dale, F. and Barna, G. 2011 (2009). Small is Big! Unleashing the Impact of Small Churches. Tyndale Publishing.

Disciple Making through the Discovery Method (DM2) Workbook 1:Understanding the Discovery Method. 2021. A Fellowship International Curriculum.

Dyrness, W. 2016. Insider Jesus: Theological Reflections on New Christian Movements. Downers Grove: IVP Academic.

Farah, W. 2015. “Towards a Missiology of Disciple Making Movements” Circumpolar. Available online at http://muslimministry.blogspot.com/2015/11/towards-missiology-of-disciple-making.html.

_____ 2020. “Motus Dei: Disciple-Making Movements and the Mission of God.” Global Missiology. Available online at http://ojs.globalmissiology.org/index.php/english/article/view/2309.

Farah, W. and Hirsch, 2021 “Movemental Ecclesiology: Recalibrating Church for the Next Frontier” ABTS. available online at https://abtslebanon.org/2021/04/15/movemental-ecclesiology-recalibrating-church-for-the-next-frontier/.

Fellowship International Disciple-Making Coaching Manual. 2021. Available online at https://www.fellowship.ca/downloads/sb_febv4/DMMManualEssentialElementsandstrategies003.pdf.

Garrison, D. 2000. Church Planting Movements (Booklet). International Mission Board.

_____ 2004. Church Planting Movements: How God Is Redeeming a Lost World. WIGTake Resources.

_____ (2014). A Wind in the House of Islam: How God is Drawing Muslims around the World to Faith in Jesus Christ. WIGTake Resources.

Hiebert, P.G. 1994. Metatheology: The Step beyond Contextualization in Anthropological Reflections on Missiological Issues. Grand Rapids: Baker, 93-103.

Kraft, CH. 1979. Christianity in culture: A Study in Dynamic Biblical Theologizing in Cross–cultural Perspective. Maryknoll: Orbis.

Kritzinger, JNJ 2010. Nurturing Missional Integrity. Unpublished paper presented to the annual meeting of the American Society of Missiology (ASM), Techny, IL, June 2010.

Long, J. 2020. “1% of the World: A Macroanalysis of 1,369 Movements to Christ” Mission Frontiers. Available online at http://www.missionfrontiers.org/issue/article/1-of-the-world-a-macroanalysis-of-1369-movements-to-christ.

Moran, R. 2021. “Disciple Making Movements – a History and a Definition” Discipleship.org. Available online at https://discipleship.org/bobbys-blog/disciple-making-movements-part-1/.

Naylor, M. 2013. Mapping Theological Trajectories that Emerge in Response to a Bible Translation. Unpublished thesis.

_____ 2020. “109. Defending DMMs” Available online at http://impact.nbseminary.com/109-defending-dmms/.

_____ 2020. “110. Response to Stiles’ Critique of DMMs” Available online at http://impact.nbseminary.com/110-response-to-stiles-critique-of-dmms/.

_____ 2020. “112. DMM Critiques addressed at FI Summit 2020” Available online at http://impact.nbseminary.com/dmm-critiques-addressed-at-fi-summit-2020/.

Newbigin, L. 1989. The Gospel in a Pluralist Society. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Prinz, E. & Coles, D. 2021. “The Person, Not the Method: An Essential Ingredient for Catalyzing a Movement” Mission Frontiers. Available online at http://www.missionfrontiers.org/issue/article/the-person-not-the-method-an-essential-ingredient-for-catalyzing-a-movement.

Sanneh, L. 2015. Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture (Revised and Expanded). Maryknoll NY: Orbis.

Slack, J. 2011. “Just How Many Church Planting Movements Are There?” Mission Frontiers. Available online at http://www.missionfrontiers.org/issue/article/just-how-many-church-planting-movements-are-there.

Smith, S. 2015. “The Lens of Kingdom Movements in Scripture” Mission Frontiers. Available online at http://www.missionfrontiers.org/issue/article/the-lens-of-kingdom-movements-in-scripture.

Stiles, Mack. 2020. “What Could Be Wrong with ‘Church Planting’? Six Dangers in a Missions Strategy” desiringGod. Available online at https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/what-could-be-wrong-with-church-planting.

Trousdale, J. 2012. Miraculous Movements: How Hundreds of Thousands of Muslims are Falling in Love with Jesus. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

Trousdale, J., and Sunshine, G. 2018. The Kingdom Unleashed: How Jesus’ 1st-Century Kingdom Values Are Transforming Thousands of Cultures and Awakening His Church. Murfreesboro TN: DMM Library.

Vegas, C. 2018. “A Brief Guide to DMM” Radius International. Available online at https://www.radiusinternational.org/a-brief-guide-to-dmm/.

Watson, D., & Watson, P. 2014. Contagious Disciple Making: Leading Others on a Journey of Discovery. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

Wright, C. J. H. 2006. The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative. Downers Grove: IVP Academic.

Endnotes

[1] Praxis refers to the “constant interplay between theory and practice, acting and thinking, praying and working, towards any kind of transformative religious or social goal” (Kritzinger 2010, 7).

[2] Compare Hiebert’s (1994, 101-102) use of “metatheology” as a set of procedures “by which different theologies, each a partial understanding of the truth in a certain context, could be constructed.” His focus on the “primary test” of Scripture and the “humility and the willingness to be led by the Spirit” is strongly reflected in DMM.

[3] See Garrison’s 2004 seminal work, Church Planting Movements: How God is Redeeming a Lost World.

[4] See Cole & Park’s (2019, Loc 4397ff) distinctions between a number of movement strategies leading to CPMs, in which DMM is included in “Appendix A: Definitions of key terms.” New Generations states that “since March 2005, the Lord has used the Disciple Making Movement (DMM) process to catalyze … new churches” (https://newgenerations.org/about-dmm/). Note that even though the DMM terminology may be used to describe methodologies with different emphases, the strategies and definitions given by New Generations/24:14/Trousdale/Watson & Watson are in view in this article.

[5] This number is based on a set of criteria that Long (2020) describes in his article.

[6] Watson & Watson (2014, 4) suggest “a minimum of one hundred new locally initiated and led churches, four generation deep, within three years,” while Garrison (2014, loc 385-91) refers to 11 movements in the last two decades of the 20th century and 69 in the first 12 years of the 21st century.

[7] Justin Long has been involved in mission research for over 25 years working on the global documentation of unreached places, peoples, and efforts to reach them. He is currently documenting movements (Long 2020).

[8] While there is variety in the lists of essential elements that describe DMM principles and practices, the following are consistently present in some form:

- Passion for prayer

- God-sized vision

- Commitment and perseverance

- Abundant sowing

- Sympathetic gatekeepers (“people of peace”)

- Small group disciple making

- Discovery methodology for disciple making

- Rapid multiplication of leaders and groups

[9] As explained in the Fellowship International Coaching Manual for DMM practitioners (2021):

- Essential Elements are 10 key biblical principles that keep us focused on the goal of joining Jesus in the expansion of God’s Kingdom.

- Strategies are the practices identified by missiologists and mission practitioners around the world and through the centuries that focus on a particular essential element.

[10] DMM theology is relatively new. Warrick Farah offers “a constructive appraisal of DMM missiology” and has coined the term “motus Dei” (movement of God) as an expression of the missio Dei (mission of God) in his 2020 article, Motus Dei: Disciple-Making Movements and the Mission of God. A previous article by Farah in 2015, Towards a Missiology of Disciple Making Movements, also discusses emerging theological concerns.

[11] The assumption is that Jesus has brought together under the call to “make disciples” all the dimensions of what it means to join God in his redemptive mission to the world. The church is called to be the people of God, “holy and beloved” (Col 3:12 NRSV), and the bride of Christ (Rev 21:9; Eph 5:25-27). The mission of the church, then, flows out of that relationship into active participation in God’s mission by inviting others to repentance and into the kingdom of God (Mt 4:17) so that they, too, can experience Jesus’ transforming redemption (Lu 4:18,19). The heart and primary activity of the church’s mission is to “make disciples” towards this end.

[12] These critiques have been responded to by a number of DMM advocates. For example, see Naylor (2020) “109. Defending DMMs” and “110. Response to Stiles’ Critique of DMMs.”

[13] Although the study Allen was involved in did not study DMMs, the description is fitting for DMM practices as well.

[14] David Watson is one example. The first chapter of Watson & Watson’s (2014, 3) book, Contagious Disciple Making, is entitled “Disciple Makers Embrace Lessons Taught from Failure.”

[15] Steve Smith (2015) provides an overview of multiplying or exponential growth evident in Scripture as God fulfills his mission.

[16] Farah and Hirsch (2021) provide a chart illustrating a “paradigm shift in church mindset” that contrasts “typical ecclesiology” with “movemental ecclesiology.” They also recognize that such distinctions may be “better understood as a continuum and not an artificial dichotomy the way it is portrayed.”

[17] “Conventional church planting efforts” refers to methodologies that usually result in “additional” growth rather than “multiplication.” The comparison between the reproductive abilities of elephants versus rabbits has been used as a provocative analogy, e.g. Dale, Dale & Barna (2011).

[18] For an introduction to a simple DBS process, see https://discoverapp.org/.

[19] For example, in Appendix D of Disciple Making through the Discovery Method (DM2) Workbook 1: Understanding the Discovery Method, a benefit of DBS is given as introducing “the major practices required of a local church”:

- Worship and praise

- Prayer and requests

- Engaging God’s word

- Conformity to God’s nature as revealed in Jesus

- Obedience to God’s will

- Evangelism

- Supporting each other in our commitment to obey

- Serving others

[20] A key question used in DBS is to describe “the nature and will of God as revealed in the passage.”

[21]See further in Naylor (2020), “112. DMM Critiques addressed at FI Summit 2020.”

[22] Note that the “believer/unbeliever” terminology comes with significant polarizing baggage in which “unbeliever” can imply a rebellious or antagonistic spirit. See Naylor (2020), “109. Defending DMMs,” for the suggestion of a transitional term, “seeker,” as more appropriate.

[23] For further development of this analogy and its relevance to the disciple making process, see Naylor 2020, 109. Defending DMMs.

[24] See further Kraft (1979, 240-245) and Bradshaw (1993, 154-156) for the directional movement of centered sets in defining believers in terms of their orientation to scripture rather than an overt commitment to a religious tradition or a statement of doctrinal faith. The point is not to disparage doctrine or declarations of faith, but to point out the priority of covenantal commitments that are supported by such doctrinal statements.